This 2015 annual report highlights the achievements of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) over the past 12 months (July 2014 through June 2015) and describes the cooperation in health between and among PAHO’s Member States and PAHO’s secretariat, the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (“the Bureau”), which also serves as Regional Office for the Americas of the World Health Organization (WHO).

This 2015 annual report highlights the achievements of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) over the past 12 months (July 2014 through June 2015) and describes the cooperation in health between and among PAHO’s Member States and PAHO’s secretariat, the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (“the Bureau”), which also serves as Regional Office for the Americas of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Pan American cooperation in health has been PAHO’s raison d’être for well over a century and is a driving force behind our Region’s impressive public health progress. With the Bureau’s coordination and technical cooperation and in partnership with other agencies and organizations, PAHO Member States have set an example for the world through their success in controlling and eliminating vaccine-preventable and neglected tropical diseases, providing antiretroviral treatment for HIV, progressing toward the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and congenital syphilis, and achieving most of the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This collaboration, its clear results, and the example it provides for other countries and regions together inspired the theme of this Annual Report: “Championing Health for Sustainable Development and Equity: Leading by Example.”

I am pleased to report that the tradition of Pan American cooperation led to significant new accomplishments over the past year. I am particularly proud of two: first, the new regional commitment to universal access to health and universal health coverage, goals that I had defined as my highest priority when I became Director in 2013. The Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage, approved by PAHO’s 53rd Directing Council, is itself a first for any WHO Region and opens the way for the Americas to become the world’s first Region to achieve universal health. The second achievement of which I am especially proud is that as a Region we were able to certify the elimination of endemic rubella virus transmission and congenital rubella syndrome, a historic milestone for public health in the Americas.

My own leadership of the Bureau during the past year was also guided by the spirit of Pan Americanism. I maintained an active and engaged dialogue with PAHO’s Member States and other partners, visiting 17 countries over the past year. I heard encouraging words about the value our members and partners place on the Bureau’s roles as a facilitator and coordinator of Pan American cooperation and as a provider of technical expertise. I was pleased and impressed to see the many innovations that are being implemented by countries throughout the Region to improve people’s health. Many of our Member States are eager to share with other countries what they know and what they do well, and to benefit from other countries’ know-how and experience in health. Promoting and facilitating this kind of “leadership by example” is precisely the aim of our new and expanded program on Cooperation among Countries for Health Development.

I also reached out to leaders of other organizations and other sectors, from international financial institutions and sister United Nations (U.N.) agencies to ministers of finance and heads of government. I advocated at every opportunity for dedication of sufficient national resources—at least 6% of GDP—to health. I emphasized the importance of ensuring that health is promoted and protected in all public policies, not just those directly related to the health sector. In recent months, I coordinated with the World Bank’s regional unit for Latin America and the Caribbean, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) to ensure that financing mechanisms were available to our Member States for Ebola preparedness. I also met with other partners, such as the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) to strengthen our long-term relationship and to advocate for greater focus on the animal-human public health interface. In all these interactions, I was gratified to see strong appreciation for PAHO’s work in the Region and a readiness to partner with us.

Internally, the Bureau continued during the past year to implement managerial, technological, and organizational changes to improve our effectiveness and efficiency and to strengthen our delivery of technical cooperation. Some of these changes put additional, albeit temporary, pressures on the Bureau’s staff, who had to dedicate time and effort to learning new systems—particularly the new PASB Management Information System (PMIS)—while continuing to carry their regular workload. These organizational efforts took place alongside our core work of advancing the PAHO Strategic Plan 2014-2019 and responding in cooperation with our Member States to pressing health challenges.

In presenting this report to PAHO’s Governing Bodies, I wish to thank each and every member of our staff for their dedicated commitment, diligence, and passion in collectively pursuing the Bureau’s mission. I am also very grateful to our Member States and other partners for their invaluable collaboration and ongoing support. I look forward to all of us working together in the new era of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to ensure that the Region of the Americas continues to lead by example, advancing health for all in our hemisphere and beyond.

Carissa F. Etienne

Director

Pan American Health Organization

Back to menu

The Region of the Americas achieved a number of significant public health milestones during the 12-month period ending in June 2015:

The Region of the Americas achieved a number of significant public health milestones during the 12-month period ending in June 2015:

These milestones were cause for celebration and recognition of the commitment, collaboration, and hard work that went into achieving them. But the Region also faced continuing and new health challenges that required critical attention and focused responses:

This report describes the work of PAHO’s secretariat, the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (“the Bureau”), together with its Member States and other partners toward these and other achievements and in response to new and persisting health challenges during the reporting period. The report also highlights the Bureau’s internal measures aimed at increasing organizational efficiency and improving its delivery of technical cooperation to Member States. Finally, the report discusses how the Bureau is positioning itself to support Member States in advancing health and equity in the new era of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Details on PAHO’s financial situation are provided in the Financial Report of the Director and Report of the External Auditor for 2014. Additional details on the Organization’s technical cooperation programs and their results through the end of 2015 will be provided in the End-of-Biennium Assessment of the Program and Budget 2014-2015, to be published in 2016.

The health milestones achieved in the Americas between July 2014 and June 2015 would not have been possible without the coordinated efforts of PAHO Member States, the Bureau, and partner organizations at the country, regional, and global levels. The Bureau’s role in these achievements included not only technical cooperation and normative guidance but also convening expertise and forging partnerships, facilitating dialogue and negotiation, and in other ways exercising and promoting “leadership by example.”

The 53rd Directing Council was a prime example of these dynamics. The historic Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage and seven regional plans of action that were adopted by the 2014 Directing Council were developed with technical expertise from the Bureau, with major contributions and feedback from Member States, and in consultation with partner agencies and civil society organizations. The result was a groundbreaking regional commitment to pursue “health for all” in the Americas.

In the past decade, the countries of the Americas have made significant progress in improving access to health systems and services. However, in a number of countries some 10%-15% of the population still experience catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures, putting them at risk of impoverishment. 1

In the past decade, the countries of the Americas have made significant progress in improving access to health systems and services. However, in a number of countries some 10%-15% of the population still experience catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures, putting them at risk of impoverishment. 1

The 2014 PAHO Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage (Document CD53/5, Rev. 2 [2014]) sets the goal, at both the regional and country levels, of ensuring that “all people and communities have access, without discrimination, to comprehensive, appropriate and timely, quality health services determined at the national level according to needs, as well as access to safe, effective, and affordable quality medicines, while ensuring that the use of such services does not expose users to financial difficulties, especially groups in conditions of vulnerability.”

The 2014 PAHO Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage (Document CD53/5, Rev. 2 [2014]) sets the goal, at both the regional and country levels, of ensuring that “all people and communities have access, without discrimination, to comprehensive, appropriate and timely, quality health services determined at the national level according to needs, as well as access to safe, effective, and affordable quality medicines, while ensuring that the use of such services does not expose users to financial difficulties, especially groups in conditions of vulnerability.”

To advance toward universal health, the strategy establishes four strategic lines of action: (1) expanding equitable access to comprehensive, quality, people- and community-centered health services; (2) strengthening stewardship and governance; (3) increasing and improving financing, with equity and efficiency, and advancing toward the elimination of direct payment that constitutes a barrier to access at the point of service; and (4) strengthening intersectoral coordination to address the social determinants of health.

The Strategy calls on the Bureau to support country action in these areas with technical cooperation and to monitor and report on the countries’ progress.

With the Bureau’s technical cooperation, by mid-2015, 11 countries had developed or were implementing national plans to advance toward universal health. Other support during the reporting period included training for 200 professionals in management of health services, financing and health economics, governance, and stewardship; studies on health system efficiency or fiscal space issues in 11 countries; assistance with developing national health accounts for 15 countries; and the development of a monitoring and evaluation framework to measure countries’ progress toward universal health. The Bureau also helped ministries of health advocate with ministers of finance and financial institutions for increased health financing.

Health systems that seek to ensure universal health must place priority on primary health care and integrated services that are staffed by professionals working in interdisciplinary teams, with special focus on groups whose health needs have traditionally been underserved. Many existing health systems in the Americas, by contrast, are fragmented, short on primary health care staff, and top-heavy with medical specialists concentrated in urban areas.

Health systems that seek to ensure universal health must place priority on primary health care and integrated services that are staffed by professionals working in interdisciplinary teams, with special focus on groups whose health needs have traditionally been underserved. Many existing health systems in the Americas, by contrast, are fragmented, short on primary health care staff, and top-heavy with medical specialists concentrated in urban areas.

To address these problems, the Bureau collaborated with 10 countries during the reporting period—Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, the United States, and Venezuela—in efforts to shift medical school paradigms toward a “social mission” in the education of doctors and other health workers. The goal is to produce health professionals with training and experience in primary care and integrated health service delivery, who are committed to the health needs of the most vulnerable and, when needed, willing to practice in underserved areas.

During the reporting period, Bureau experts worked with ministries of health and medical schools in the 10 participating countries to define national-level education and training requirements for professionals in community health centers and to develop technical recommendations for in-service training programs in those centers. The project also produced a preliminary set of indicators to measure progress in incorporating the social mission paradigm in medical schools and medical training.

Despite its strong commitment to universal health, Brazil—like many other countries—has found it difficult to meet the health needs of vulnerable populations and remote communities. Indeed, Brazil’s size and geography make the goal of universal health especially challenging.

Despite its strong commitment to universal health, Brazil—like many other countries—has found it difficult to meet the health needs of vulnerable populations and remote communities. Indeed, Brazil’s size and geography make the goal of universal health especially challenging.

Brazil’s Mais Médicos program addresses these challenges by increasing the availability of medical training in its national universities, improving incentives for health professionals to work in underserved areas, and, as needed, recruiting personnel from outside the country to provide health services in underserved communities. Since its inception in 2013, Mais Médicos has expanded access to primary health care to more than 60 million people in Brazil. The country has also invested 5.6 billion reales (nearly US$ 1.8 billion) in health infrastructure as part of the program.

The Bureau has supported the Mais Médicos program with technical cooperation and, in particular, assistance in integrating members of Cuba’s international medical brigades. As of mid-2015, more than 11,400 Cuban doctors were participating in the program, along with some 5,600 Brazilians and more than 1,000 doctors and health care workers from other countries. The Bureau has also supported Brazil’s development of a monitoring and evaluation framework for the program and in documenting best practices and lessons learned to share with other PAHO Member States.

Two independent evaluations of Brazil’s Mais Médicos program have shown positive results.2 In the first study, 95% of users reported being satisfied with the performance of participating doctors, while 86% said the quality of care had improved as a result of the program. The second study found that waiting times in clinics had declined 89% since the program began, despite an increase of 33% in the average monthly number of visits. The number of doctor home visits had also increased, by 32%.

In March 2015, the Bureau followed up on its 2013 proposed policy for Cooperation for Health Development in the Americas (Document CD52/11 [2013]) by convening a consultation in Panama. Some 80 participants from 26 Member States joined representatives of Associate Member States, subregional integration entities, and partner agencies of the United Nations and inter-American systems to review the policy and make recommendations on strategies and mechanisms for implementing it. Using these recommendations along with the results of a Bureau-wide survey and a review of PAHO’s country-to-country cooperation experiences from 2008 to 2013, the Bureau produced a proposed new Cooperation among Countries for Health Development (CCHD) framework.

In March 2015, the Bureau followed up on its 2013 proposed policy for Cooperation for Health Development in the Americas (Document CD52/11 [2013]) by convening a consultation in Panama. Some 80 participants from 26 Member States joined representatives of Associate Member States, subregional integration entities, and partner agencies of the United Nations and inter-American systems to review the policy and make recommendations on strategies and mechanisms for implementing it. Using these recommendations along with the results of a Bureau-wide survey and a review of PAHO’s country-to-country cooperation experiences from 2008 to 2013, the Bureau produced a proposed new Cooperation among Countries for Health Development (CCHD) framework.

Also during the reporting period, the Bureau updated the PAHO Key Country Strategy, which guides the Organization’s technical cooperation with Bolivia, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Suriname. A major aim was to identify specific approaches to provide these countries with special support for their pressing health challenges. The updated strategy uses the framework of the renewed WHO Country Focus Strategy and incorporates input from the Bureau’s department heads and PAHO/WHO Representatives (PWRs). The final version was presented to PAHO’s Senior Advisory Group in February 2015 and approved by senior management for incorporation into the Bureau’s technical cooperation.

Ensuring access to safe and effective medicines and health technologies is an essential public health function and is critical to achieving universal health. As part of efforts to build capacity in this area in Member States, the Bureau worked with members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) to develop the Caribbean Regulatory System initiative. An implementation policy and proposal for the system was endorsed by CARICOM ministers of health in September 2014.

Ensuring access to safe and effective medicines and health technologies is an essential public health function and is critical to achieving universal health. As part of efforts to build capacity in this area in Member States, the Bureau worked with members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) to develop the Caribbean Regulatory System initiative. An implementation policy and proposal for the system was endorsed by CARICOM ministers of health in September 2014.

The initiative’s goal is to increase access to safe, effective, affordable, and quality-assured medicines and health technologies for small island states of the Caribbean, which face special challenges in this regard. The proposed system will be based at the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) and will initially focus on registration of priority generic medicines that have already been approved by a PAHO-designated national regulatory authority (NRA) of regional reference.3

The Regional Revolving Fund for Strategic Public Health Supplies, known as the PAHO Strategic Fund, continued to play an important role in promoting access to high-quality, essential public health supplies for Member States. From June 2014 through June 2015, 17 of the Region’s countries used the Fund to procure approximately US$ 66 million in medicines and other essential public health supplies; three countries used the Fund’s capital account to avoid the risk of drug shortages. During the reporting period, PAHO issued its first long-term agreements (LTAs) with manufacturers to establish standard prices for all Member States on 23 medicines used to treat noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

Infectious diseases have continued to be a major public health challenge in the Americas despite the ongoing epidemiological transition toward NCDs. During the reporting period, PAHO Member States made significant progress in prevention and control of communicable diseases. The Bureau’s extensive technical cooperation ranged from support for elimination of neglected and vaccine-preventable diseases to helping countries obtain external financing to fight HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria.

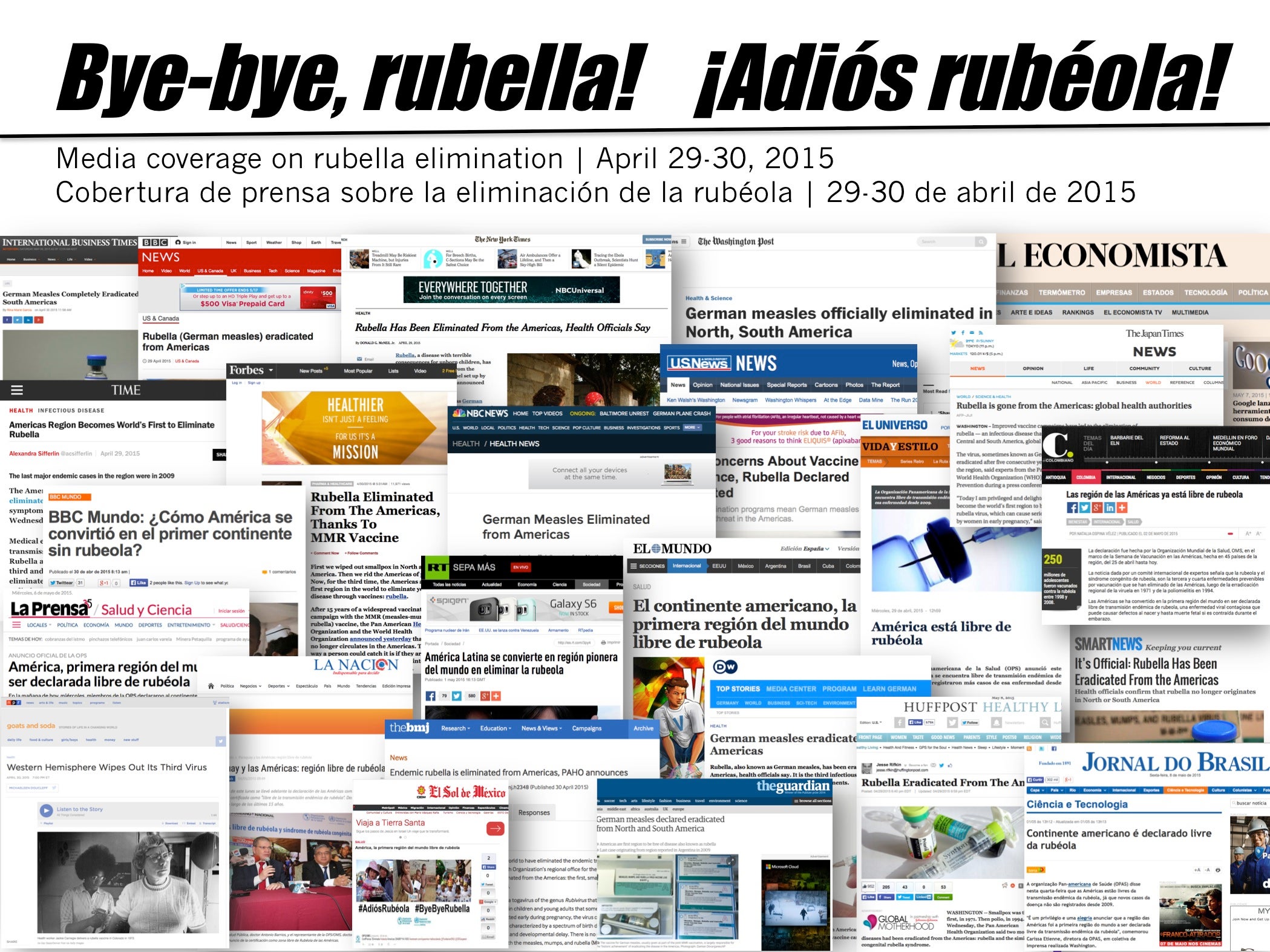

A major highlight of the reporting period was the announcement in April 2015 that the Americas had become the world’s first Region to eliminate rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Rubella and CRS were the third and fourth diseases to be eliminated first in the Americas, following smallpox in 1971 and polio in 1994.

A major highlight of the reporting period was the announcement in April 2015 that the Americas had become the world’s first Region to eliminate rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Rubella and CRS were the third and fourth diseases to be eliminated first in the Americas, following smallpox in 1971 and polio in 1994.

The declaration was made by the International Expert Committee for Measles and Rubella Elimination in the Americas after reviewing epidemiological evidence and determining that no endemic transmission of rubella virus or cases of CRS had occurred in the Region since 2009, exceeding the three-year requirement for elimination.

The achievement was the culmination of a 15-year consolidated effort to eliminate both measles and rubella that was coordinated by the Bureau and supported by ministries of health, donors and other international partners, and health workers throughout the Region. In making the announcement, the International Expert Committee said that it hoped to declare measles eliminated from the Americas in the near future.

The announcement of rubella and CRS elimination came during the 13th annual Vaccination Week in the Americas, which took place from April 25 to May 2. Vaccination Week historically played a key supporting role in the elimination of rubella and CRS by making vaccines widely available throughout the Region, and especially to vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations.

The announcement of rubella and CRS elimination came during the 13th annual Vaccination Week in the Americas, which took place from April 25 to May 2. Vaccination Week historically played a key supporting role in the elimination of rubella and CRS by making vaccines widely available throughout the Region, and especially to vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations.

With the slogan “Boost your power! Get vaccinated!” the 2015 initiative targeted more than 60 million children and adults with vaccines against diseases that included measles and rubella, seasonal influenza, polio, and neonatal tetanus. More than a dozen countries also used the opportunity to combine immunization with other public health interventions, including deworming and vitamin A supplementation, diabetes and hypertension screening, HIV testing, sexual and reproductive health education, and vaccination of pets. In addition to ministries of health, other partners included UNICEF, UNAIDS, UNDP, the Sabin Vaccine Institute, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Since its inception in 2003, Vaccination Week in the Americas has reached more than half a billion people throughout the hemisphere.

The Revolving Fund for Vaccine Procurement, as part of PAHO’s comprehensive technical cooperation approach on immunization, has provided crucial support for the Region’s achievements, including its elimination of vaccine-preventable diseases and its introduction of new vaccines, such as for rotavirus, pneumococcal disease, and human papillomavirus (HPV). A noteworthy achievement was the Bureau’s successful negotiations to make both HPV vaccines currently on the market available for procurement through the Fund at reduced prices.

The Revolving Fund for Vaccine Procurement, as part of PAHO’s comprehensive technical cooperation approach on immunization, has provided crucial support for the Region’s achievements, including its elimination of vaccine-preventable diseases and its introduction of new vaccines, such as for rotavirus, pneumococcal disease, and human papillomavirus (HPV). A noteworthy achievement was the Bureau’s successful negotiations to make both HPV vaccines currently on the market available for procurement through the Fund at reduced prices.

Between June 2014 and June 2015, the Fund procured more than US$ 547 million worth of vaccines and US$ 3.5 million worth of syringes for immunization programs in 41 participating countries and territories. The PAHO Revolving Fund has become an example for other international organizations and other WHO regions of an effective mechanism to ensure an uninterrupted supply of affordable, quality vaccines in the complex global vaccine market. Increasing Member States’ awareness of global vaccine market dynamics and challenges, support for demand planning, and ensuring the timely availability of quality vaccines and supplies are key elements of PAHO’s technical cooperation.

A key area of support for Member States’ efforts to fight infectious diseases was the Bureau’s assistance in mobilizing resources from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. During the reporting period, Bureau staff at the regional and country levels worked with health officials in 14 of the Region’s Fund-eligible Member States on 23 funding proposals addressing specific challenges related to HIV, TB, and malaria. By June 2015, 11 of these proposals had been approved by the Fund, representing US$ 146,895,670 in new resources, while results were pending from the Fund’s technical review of the remaining 12 proposals.

A key area of support for Member States’ efforts to fight infectious diseases was the Bureau’s assistance in mobilizing resources from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. During the reporting period, Bureau staff at the regional and country levels worked with health officials in 14 of the Region’s Fund-eligible Member States on 23 funding proposals addressing specific challenges related to HIV, TB, and malaria. By June 2015, 11 of these proposals had been approved by the Fund, representing US$ 146,895,670 in new resources, while results were pending from the Fund’s technical review of the remaining 12 proposals.

The funding catalyzed by PAHO during this period will support efforts to address issues that continue to negatively impact primarily vulnerable populations. These include:

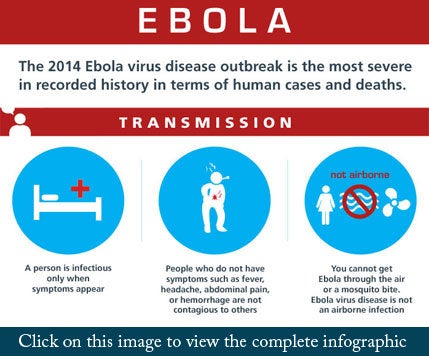

Following the exponential spread of Ebola in West Africa during the second half of 2014, the Bureau worked proactively with its Member States to raise awareness and strengthen preparedness for the potential introduction of the virus into the Americas.

Following the exponential spread of Ebola in West Africa during the second half of 2014, the Bureau worked proactively with its Member States to raise awareness and strengthen preparedness for the potential introduction of the virus into the Americas.

In October 2014, days after the United States confirmed its first imported Ebola case, PAHO’s Director established a task force to assess the Ebola risk in Latin America and the Caribbean and to propose a set of actions to improve countries’ preparedness. The result was a Framework for Strengthening National Preparedness for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in the Americas. Following consultations with Member States, the Bureau mobilized 25 country missions staffed by its own experts as well as experts from the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), the U.S. CDC’s Caribbean office, and WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN). Conducted between November 2014 and January 2015, these missions to the countries helped them identify their gaps in preparedness (see box) and priority areas for action. In a third phase, the Bureau supported countries in implementing the missions’ recommendations and in assessing their future needs.

PAHO expert missions identified a number of gaps in Member States’ preparedness for the possible introduction of Ebola. Among the missions’ findings were:

PAHO expert missions identified a number of gaps in Member States’ preparedness for the possible introduction of Ebola. Among the missions’ findings were:

(1) Some countries rely excessively on port-of-entry screening to identify and prevent the introduction of a potential case of Ebola virus disease (EVD) while placing less emphasis on health services, where a first case is most likely to present.

(2) Epidemiological capacity and health services are not well coordinated; insufficient emphasis is placed on the detection of unusual health events and combined use of clinical and epidemiological information (such as unusual constellations of symptoms and travel histories) by health-care workers.

(3) Fragmentation of health services is a challenge for effective management of an EVD-related event, from detection to treatment and disinfection.

(4) Shipment of samples to the Biosafety Level (BSL) 4 laboratories at the WHO Collaborating Centers for confirmation of Ebola virus infections poses major challenges. Only four countries have BSL-3 laboratories with EVD diagnostic capacity.

(5) Countries have designated isolation areas but limited numbers of trained personnel. Several countries are unlikely to meet the conditions for safely treating a potential or confirmed EVD case due to crumbling hospital infrastructure and lack of infection prevention and control programs.

(6) Countries lack sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) to manage a patient according to infection prevention and control risk assessment principles. Moreover, they have limited ability to procure PPE given current global shortages.

management of Ebola, risk communication, infection prevention and control, and laboratory diagnosis and biosafety. Over a six-month period, more than 1,600 professionals received training in these areas.

management of Ebola, risk communication, infection prevention and control, and laboratory diagnosis and biosafety. Over a six-month period, more than 1,600 professionals received training in these areas.

Chikungunya—which first emerged in the Americas via Sint Maarten in late 2013—continued to spread throughout the Caribbean and beyond during the reporting period. By June 2015, 40 countries and territories had reported local transmission of the virus, for a regional total of more than 1.5 million cases and 238 deaths. In collaboration with the U.S. CDC, the Bureau developed and piloted tools to characterize cases and classify chikungunya deaths, established mechanisms to share laboratory samples, and provided countries with laboratory reagents and quality control panels for diagnosis of the disease. The Bureau also published weekly epidemiological updates on the disease’s spread.

Chikungunya—which first emerged in the Americas via Sint Maarten in late 2013—continued to spread throughout the Caribbean and beyond during the reporting period. By June 2015, 40 countries and territories had reported local transmission of the virus, for a regional total of more than 1.5 million cases and 238 deaths. In collaboration with the U.S. CDC, the Bureau developed and piloted tools to characterize cases and classify chikungunya deaths, established mechanisms to share laboratory samples, and provided countries with laboratory reagents and quality control panels for diagnosis of the disease. The Bureau also published weekly epidemiological updates on the disease’s spread.

In May 2015, Brazil confirmed the first local transmission in the Americas of Zika virus, another Flavivirus that causes symptoms similar to those of chikungunya and dengue. The Bureau, in collaboration with other partners, developed and disseminated technical guidelines and algorithms for diagnosing the virus, and also facilitated relevant training for Member States.

Progress toward eliminating mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis continued during the reporting period, in line with the 2010 Plan of Action for the Elimination of Mother-to-Child transmission of HIV and Congenital Syphilis (Document CD50/15 [2010]). The Bureau provided targeted technical cooperation to countries with major coverage gaps in essential services, including capacity-building, strengthening of laboratory networks and services, and country evaluations. A new guidance document on scaling-up of syphilis testing was also developed through a regional consensus-building process in collaboration with the U.S. CDC.

Progress toward eliminating mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis continued during the reporting period, in line with the 2010 Plan of Action for the Elimination of Mother-to-Child transmission of HIV and Congenital Syphilis (Document CD50/15 [2010]). The Bureau provided targeted technical cooperation to countries with major coverage gaps in essential services, including capacity-building, strengthening of laboratory networks and services, and country evaluations. A new guidance document on scaling-up of syphilis testing was also developed through a regional consensus-building process in collaboration with the U.S. CDC.

In December 2014, the Bureau, with support from WHO and UNICEF, published an update on regional progress toward the goals set in the 2010 plan of action. Among the report’s findings: between 2010 and 2013, HIV testing and counseling of pregnant women increased by 18%, reaching 74% at the regional level; antiretroviral treatment increased more than 57%, to 93% of pregnant women with HIV; and syphilis testing of pregnant women remained stable at 80%. In addition, data from seven countries and territories—Anguilla, Barbados, Canada, Cuba, Montserrat, Puerto Rico, and the United States—were strongly consistent with a profile of elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis. 4

During the reporting period, four new cities—Guatemala City, Guatemala; Tijuana, Mexico; Asunción, Paraguay; and Montevideo, Uruguay—became part of the Tuberculosis Control in Large Cities initiative, a PAHO initiative supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). By June 2015, three other cities were in the pipeline to join, for a total of 11 cities across the Region participating in this innovative program, which seeks to accelerate TB control by using an all-of-society approach.

During the reporting period, four new cities—Guatemala City, Guatemala; Tijuana, Mexico; Asunción, Paraguay; and Montevideo, Uruguay—became part of the Tuberculosis Control in Large Cities initiative, a PAHO initiative supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). By June 2015, three other cities were in the pipeline to join, for a total of 11 cities across the Region participating in this innovative program, which seeks to accelerate TB control by using an all-of-society approach.

The Bureau officially engaged as a partner in the Haiti Malaria Elimination Consortium, launched in February 2015 with a US$ 29.9 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support malaria elimination efforts on the island of Hispaniola. With the U.S. CDC as lead, the consortium includes PAHO, the Carter Center, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Tulane University’s Center for Applied Malaria Research and Evaluation.

The consortium’s work will also contribute to meeting the targets set by the Global Fund–supported Elimination of Malaria in Mesoamerica and Hispaniola initiative and the binational Haiti–Dominican Republic plan to eliminate malaria and lymphatic filariasis from Hispaniola by 2020. Of the 21 malaria-endemic countries in the Americas, 14 have ongoing efforts toward malaria elimination. In response to a request from Argentina, the Bureau and WHO initiated the process to certify malaria elimination from its national territory.

The Region also made progress toward the elimination of neglected infectious diseases during the reporting period, in particular, onchocerciasis and Chagas disease. In September 2014, Ecuador became the world’s second country (after Colombia in 2013) to be verified as having eliminated onchocerciasis, or “river blindness.” In the following months, Guatemala and Mexico submitted requests for verification. Only two foci of the disease now remain in the Americas, both in the Yanomami area on the border between Brazil and Venezuela.

The Region also made progress toward the elimination of neglected infectious diseases during the reporting period, in particular, onchocerciasis and Chagas disease. In September 2014, Ecuador became the world’s second country (after Colombia in 2013) to be verified as having eliminated onchocerciasis, or “river blindness.” In the following months, Guatemala and Mexico submitted requests for verification. Only two foci of the disease now remain in the Americas, both in the Yanomami area on the border between Brazil and Venezuela.

Also in 2014, the State of São Paulo, Brazil, received verification from an international expert team assembled by PAHO/WHO that it had eliminated Chagas disease as a public health problem. Despite progress in Brazil and other affected countries, an estimated 6 million people in the Americas remain infected with Chagas disease.

In 2014, PAHO’s Regional Core Health Data and Country Profile initiative celebrated the 20th anniversary of its publication, “Health Situation in the Americas: Basic Indicators.” The 12-page brochure is published annually and provides high-quality, up-to-date data to guide the Bureau’s technical cooperation and to facilitate monitoring and follow-up of regional and global health goals. Data are compiled, processed, and reviewed in collaboration with ministries of health and planning and statistics offices in Member States. The initiative is part of the PAHO/WHO Regional Health Observatory.

In 2014, PAHO’s Regional Core Health Data and Country Profile initiative celebrated the 20th anniversary of its publication, “Health Situation in the Americas: Basic Indicators.” The 12-page brochure is published annually and provides high-quality, up-to-date data to guide the Bureau’s technical cooperation and to facilitate monitoring and follow-up of regional and global health goals. Data are compiled, processed, and reviewed in collaboration with ministries of health and planning and statistics offices in Member States. The initiative is part of the PAHO/WHO Regional Health Observatory.

In January 2015, PAHO’s Pan American Foot-and-Mouth Disease Center (PANAFTOSA) in Rio de Janeiro marked the animal health milestone of three consecutive years in the Americas without this debilitating and often fatal livestock disease. Thanks to these same efforts, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay received formal recognition of their FMD-free status from the OIE.

In January 2015, PAHO’s Pan American Foot-and-Mouth Disease Center (PANAFTOSA) in Rio de Janeiro marked the animal health milestone of three consecutive years in the Americas without this debilitating and often fatal livestock disease. Thanks to these same efforts, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay received formal recognition of their FMD-free status from the OIE.

The absence of FMD ensures healthier and more productive animal husbandry, promotes food security, and helps maintain the value of the Region’s international exports, thus contributing to socioeconomic development.

To protect these achievements, PANAFTOSA established a foot-and-mouth disease vaccine and antigen bank (at the request of the South American Commission for the Fight against Foot-and-Mouth Disease, COSALFA) and a new Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Organisation for Animal Health (FAO/OIE) reference laboratory for FMD at Brazil’s National Agricultural Laboratory in Minas Gerais.

In the Caribbean, the Bureau coordinated with the University of the West Indies, the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), and FAO to launch the “One Health Leadership Series,” a capacity-building program that promotes cross sector action by bringing together professionals from the health, agriculture, and environmental sectors. The program is based on CARICOM’s “One Health” policy, which was developed by PAHO and FAO and was ratified by the subregion’s ministers of health in 2014 and its ministers of environment in 2015. The policy and leadership series address health issues at the human-animal-environment interface, including food security, tourism, zoonotic diseases, water supply and quality, and climate change.

The number of people suffering and dying from NCDs in the Americas continues to grow, as a result of population growth and aging, and despite success in reducing rates of cardiovascular disease. PAHO’s most recent data show that 4.5 million people die every year in the Region from NCDs and their risk factors, 1.5 million of them prematurely (between ages 30 and 69). Mitigating this growing burden and its impact on health systems is critical to ensure progress toward universal health. During 2014-2015, the Bureau’s technical cooperation on NCDs ranged from support for country legislation and regulations on tobacco, alcohol, and other risk factors to pilot studies of a new model for improving hypertension treatment and control.

The number of people suffering and dying from NCDs in the Americas continues to grow, as a result of population growth and aging, and despite success in reducing rates of cardiovascular disease. PAHO’s most recent data show that 4.5 million people die every year in the Region from NCDs and their risk factors, 1.5 million of them prematurely (between ages 30 and 69). Mitigating this growing burden and its impact on health systems is critical to ensure progress toward universal health. During 2014-2015, the Bureau’s technical cooperation on NCDs ranged from support for country legislation and regulations on tobacco, alcohol, and other risk factors to pilot studies of a new model for improving hypertension treatment and control.

An important development in this area was the adoption by PAHO Member States of a new Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents (Document CD53/9, Rev. 2 [2014]) in October 2014. The first of its kind in any WHO Region, the plan seeks to halt the Region’s rapidly growing obesity epidemic in children and youths, the age group whose nutritional status and eating patterns will shape future health.

The plan targets the increasingly “obesogenic” environments in which children are growing up in the Americas as a result of urbanization, modernization, and global marketing and trade. These forces have increased both the availability and the affordability of energy-dense, nutrient-poor ultra-processed foods and beverages at the expense of whole, fresh foods, while also reducing opportunities for physical activity.

To counteract these conditions, the plan proposes five strategic lines of action: (1) primary health care and promotion of breastfeeding and healthy eating; (2) improvement of school nutrition and physical activity environments; (3) fiscal policies and regulation of food marketing and labeling; (4) other multisectoral actions; and (5) surveillance, research, and evaluation.

Reducing exposure to alcohol, tobacco, and unhealthy foods by making the “healthy choice the easy choice” has been shown to be one of the most cost-effective ways of reducing NCDs. PAHO’s new REGULA (Strengthening the Regulatory Capacity for NCD Risk Factors) initiative is aimed at strengthening countries’ abilities to develop and implement legislative, regulatory, and fiscal measures toward this end. Examples include increased taxes on sugary beverages, price incentives for healthy food products, front-of-package nutrition labeling and health warnings, and restrictions on marketing of harmful products.

Reducing exposure to alcohol, tobacco, and unhealthy foods by making the “healthy choice the easy choice” has been shown to be one of the most cost-effective ways of reducing NCDs. PAHO’s new REGULA (Strengthening the Regulatory Capacity for NCD Risk Factors) initiative is aimed at strengthening countries’ abilities to develop and implement legislative, regulatory, and fiscal measures toward this end. Examples include increased taxes on sugary beverages, price incentives for healthy food products, front-of-package nutrition labeling and health warnings, and restrictions on marketing of harmful products.

During the reporting period, the Bureau developed a technical reference document as part of the REGULA initiative and convened a group of experts from Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and the United States to review the document and propose lines of action for technical cooperation in this area. The group identified four key lines of action for the Bureau: (1) ongoing surveillance of NCD risk factors and evaluation of regulatory processes; (2) development of organizational structures, financing, and processes for regulatory entities; (3) development of technical expertise on controlling NCD risks; and (4) promotion of research on the effectiveness of, and best practices in, regulatory action to reduce NCD risks.

In January 2015, the Bureau brought together experts on alcohol marketing and regulation from countries in the Americas and Europe and from Australia, India, and South Africa to review evidence on the effects of alcohol marketing, particularly on young people, and on the effectiveness of voluntary as opposed to statutory regulation. The experts concluded that alcohol advertising and promotion should be regulated, monitored, and evaluated by governments independently of the alcohol industry and that comprehensive bans on alcohol marketing are most effective. They called on the Bureau to provide guidance to Member States in developing and enacting legislation in this regard.

PAHO’s SaltSmart Consortium is an example of voluntary collaboration between health advocates and the private sector to advance public health goals. The initiative builds on successful efforts to persuade food makers in several countries of the Americas to lower the salt content of processed foods, in line with global and regional recommendations for reducing high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. In 2014, the consortium produced a series of principles and specific targets to guide efforts throughout the Region to reduce salt in foods ranging from bread and crackers to soups and processed meats.

PAHO’s SaltSmart Consortium is an example of voluntary collaboration between health advocates and the private sector to advance public health goals. The initiative builds on successful efforts to persuade food makers in several countries of the Americas to lower the salt content of processed foods, in line with global and regional recommendations for reducing high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. In 2014, the consortium produced a series of principles and specific targets to guide efforts throughout the Region to reduce salt in foods ranging from bread and crackers to soups and processed meats.

Not surprisingly, mandatory laws and regulations aimed at reducing consumption of tobacco, alcohol, sugary beverages, and ultra-processed foods have provoked resistance from producers of these products. Industry opposition has ranged from efforts to influence the public and intragovernmental debates to legal action to block the implementation of such measures.

Not surprisingly, mandatory laws and regulations aimed at reducing consumption of tobacco, alcohol, sugary beverages, and ultra-processed foods have provoked resistance from producers of these products. Industry opposition has ranged from efforts to influence the public and intragovernmental debates to legal action to block the implementation of such measures.

Pursuant to requests from some Member States, the Bureau has supported governments not only in the technical aspects of effective legislation and regulations but also in countering industry attempts to undermine these measures. Examples during the reporting period included:

Adding to the list of public health firsts during the past year, PAHO’s 53rd Directing Council approved the Regional Plan of Action on Health in All Policies (Document CD53/10, Rev. 1 [2014]), the first of its kind among WHO regions. The plan promotes a public policy approach that systematically considers the potential health implications of all policy decisions, seeks to create synergies to protect and promote health, and addresses the social and environmental conditions that impact health.

Adding to the list of public health firsts during the past year, PAHO’s 53rd Directing Council approved the Regional Plan of Action on Health in All Policies (Document CD53/10, Rev. 1 [2014]), the first of its kind among WHO regions. The plan promotes a public policy approach that systematically considers the potential health implications of all policy decisions, seeks to create synergies to protect and promote health, and addresses the social and environmental conditions that impact health.

The Bureau convened an expert consultation in March 2015 in which leading global experts produced a five-year roadmap with recommendations and proposed actions to implement the regional plan of action. In line with their recommendations, the Bureau established a special task force to define a core group of indicators from across the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework that can be used to promote intersectoral actions and monitor their impact on health. The task force will also provide countries with demand-based technical expertise and guidance on implementing the SDGs.

Also in line with the recommendations of the expert consultation, Suriname hosted the first subregional training on health in all policies for ministerial technical staff, policy advisors, and members of nongovernmental organizations.

National averages are poor indicators for analyzing and addressing inequities in health. As part of its longstanding commitment to health equity and sustainable development, the Bureau in 2014 adopted a new set of metrics for measuring changes in health inequality. The metrics, which underwent a rigorous critical review, consist of two measures of inequality for use in conjunction with four key indicators: infant mortality, maternal mortality, premature mortality due to NCDs, and mortality amenable to health care, that is, premature deaths that would not have occurred in the presence of timely and effective health care.

National averages are poor indicators for analyzing and addressing inequities in health. As part of its longstanding commitment to health equity and sustainable development, the Bureau in 2014 adopted a new set of metrics for measuring changes in health inequality. The metrics, which underwent a rigorous critical review, consist of two measures of inequality for use in conjunction with four key indicators: infant mortality, maternal mortality, premature mortality due to NCDs, and mortality amenable to health care, that is, premature deaths that would not have occurred in the presence of timely and effective health care.

The new metrics consist of one absolute gradient indicator, the “slope index of inequality,” and a relative gap indicator, the “relative range difference.” Both are to be applied to the four health indicators, using country groupings defined by the Health Needs Index established in the PAHO Budget Policy. The new metrics were approved by PAHO’s Directing Council in 2014, and their adoption makes the Bureau the first WHO regional office—and the first agency of the U.N. System—to use measurable health equity indicators and targets to evaluate the impact of its own technical cooperation programs.

Climate change is recognized as a serious threat to public health. At the global level, WHO estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will produce an additional 250,000 deaths annually due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress.

Climate change is recognized as a serious threat to public health. At the global level, WHO estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will produce an additional 250,000 deaths annually due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress.

As part of its work in this area, the Bureau took a leadership role at the 20th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC CoP20), held in December 2014 in Lima, Peru. Together with Peru’s Minister of Health, the Bureau helped persuade negotiators to include health (which had been omitted) in working documents and to explicitly consider the health dimensions of climate change, especially as related to issues of equity. This achievement set the stage for the public health community to ensure, going forward, that health and health equity are priority issues in the “elements” text that will be negotiated in December 2015. It also presents an opportunity to highlight the health benefits of well-planned mitigation actions, including those aimed at reducing air pollution.

Also during the reporting period, the Bureau brought together representatives of 15 countries of the Region to prepare for the implementation the WHO Air Quality Guidelines, which seek to mitigate air pollution and its impact on both climate change and health at the local level. In the context of the guidelines, participants reviewed existing national programs in their countries for reducing the use of solid fuels and transitioning to cleaner technologies and fuels.

Hurricanes, tropical storms, and other weather-related disasters can significantly disrupt access to health services. However, the health sector itself is a major contributor to climate change through the environmental impact of health facilities. PAHO’s Smart Hospitals initiative helps countries reduce the environmental footprint of new or existing health facilities while also increasing their safety and resilience in case of disasters.

Hurricanes, tropical storms, and other weather-related disasters can significantly disrupt access to health services. However, the health sector itself is a major contributor to climate change through the environmental impact of health facilities. PAHO’s Smart Hospitals initiative helps countries reduce the environmental footprint of new or existing health facilities while also increasing their safety and resilience in case of disasters.

During the reporting period, the Bureau worked with health and disaster response authorities in Belize, the British Virgin Islands, and Grenada to review proposed and existing health facilities using the Smart Hospitals checklist, in order to increase their water and energy efficiency and to reduce risks. Belize’s Ministry of Health used the results of the review to persuade the Ministry of Finance to allocate more resources to the health sector.

Following a successful first phase of the Smart Hospitals initiative in Saint Kitts and Nevis, the U.K. Department for International Development (DFID) decided in May 2015 to extend support for the initiative’s implementation in Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

In May 2015, the Bureau published its latest Report on Road Safety in the Region of the Americas. The report shows that some 150,000 people died from traffic injuries in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2010. Of these deaths, 27% were pedestrians, 20% motorcyclists, and 3.7% were bicyclists. The report also notes that 42% of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean is now protected by drinking-and-driving laws. However, of the 14 countries that have legislation setting blood alcohol concentration limits, only 5 of them—Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, Panama, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines—report having strong enforcement. Similarly, laws on motorcycle helmet use have improved, but more efforts are needed to enforce those laws and ensure that helmets meet quality standards. The report calls for stronger traffic law enforcement to reduce road deaths and especially to protect the most vulnerable road users.

In May 2015, the Bureau published its latest Report on Road Safety in the Region of the Americas. The report shows that some 150,000 people died from traffic injuries in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2010. Of these deaths, 27% were pedestrians, 20% motorcyclists, and 3.7% were bicyclists. The report also notes that 42% of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean is now protected by drinking-and-driving laws. However, of the 14 countries that have legislation setting blood alcohol concentration limits, only 5 of them—Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, Panama, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines—report having strong enforcement. Similarly, laws on motorcycle helmet use have improved, but more efforts are needed to enforce those laws and ensure that helmets meet quality standards. The report calls for stronger traffic law enforcement to reduce road deaths and especially to protect the most vulnerable road users.

In March 2015, the Bureau published the Status Report on Violence Prevention in the Region of the Americas, 2014. It provides updated information on interpersonal violence prevention in the Americas, based on the Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014, a collaborative report produced by WHO and its regional offices, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

For the regional report, the Bureau gathered information from 21 countries in the Americas, representing 88% of the Region’s population. The report estimates that in 2012 there were 165,617 deaths in low- and middle-income countries of Latin America and the Caribbean that were due to homicide, and three-quarters of these were carried out with firearms. This represents 28.5 homicides per 100,000 people, more than four times the global homicide rate (6.7 per 100,000). The report also finds that three-quarters of the Region’s countries have national action plans to reduce violence, and all countries have laws regulating firearms. However, a third of these were lacking data, suggesting that much planning and policymaking is done in the absence of evidence.

For the regional report, the Bureau gathered information from 21 countries in the Americas, representing 88% of the Region’s population. The report estimates that in 2012 there were 165,617 deaths in low- and middle-income countries of Latin America and the Caribbean that were due to homicide, and three-quarters of these were carried out with firearms. This represents 28.5 homicides per 100,000 people, more than four times the global homicide rate (6.7 per 100,000). The report also finds that three-quarters of the Region’s countries have national action plans to reduce violence, and all countries have laws regulating firearms. However, a third of these were lacking data, suggesting that much planning and policymaking is done in the absence of evidence.

The status report will support policymaking in Member States and the design of effective plans and initiatives, including programs to reduce the availability and harmful use of alcohol, laws and programs to reduce access to firearms and knives, efforts to change gender norms that help perpetuate violence against women, programs to improve parenting and life skills in children and adolescents, and public information campaigns to prevent elder abuse.

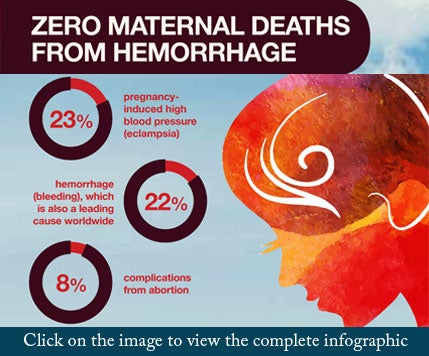

Maternal health remains an area of major concern throughout the Region and a special challenge for progress toward universal health. Millennium Development Goal 5 was one of the few MDGs that Latin America and the Caribbean did not achieve: though maternal deaths declined an average 2.2% per year, this was less than half the 5.5% annual decline needed to achieve MDG 5. This shortfall was the result of gaps in countries’ abilities to ensure quality, comprehensive and universally accessible sexual and reproductive health services, in addition to poverty and other social determinants of health.

Maternal health remains an area of major concern throughout the Region and a special challenge for progress toward universal health. Millennium Development Goal 5 was one of the few MDGs that Latin America and the Caribbean did not achieve: though maternal deaths declined an average 2.2% per year, this was less than half the 5.5% annual decline needed to achieve MDG 5. This shortfall was the result of gaps in countries’ abilities to ensure quality, comprehensive and universally accessible sexual and reproductive health services, in addition to poverty and other social determinants of health.

A priority area of action during the reporting period was improving the ability of health professionals in perinatal care to respond to obstetric hemorrhage, one of the leading causes of maternal death. These efforts were part of the “Zero Maternal Deaths from Hemorrhage” initiative, spearheaded by PAHO’s Latin American Center for Perinatology/Women’s Reproductive Health (CLAP/SMR) with support from the Latin American Federation of Societies of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The initiative targets subnational areas with high maternal mortality ratios (over 70 per 100,000 live births). Participating countries include Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Paraguay, and Peru.

The Bureau provided training for health professionals from these countries on effective management of obstetric hemorrhage in clinical settings and through national work plans. The Bureau also provided 16 birthing simulators and 32 non-pneumatic anti-shock garments for use in national-level workshops in which some 210 additional health providers received training. Most recently, Nicaragua also adopted the same training approach.

The Bureau provided training for health professionals from these countries on effective management of obstetric hemorrhage in clinical settings and through national work plans. The Bureau also provided 16 birthing simulators and 32 non-pneumatic anti-shock garments for use in national-level workshops in which some 210 additional health providers received training. Most recently, Nicaragua also adopted the same training approach.

During the reporting period, the Bureau served as the technical secretariat for “A Promise Renewed for the Americas,” an interagency movement working to reduce the profound inequities in reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child, and adolescent health that persist in Latin America and the Caribbean. Work during the period included the identification of funding gaps and funding opportunities, the creation of a digital database for articles and documents on health inequalities, and a series of regional events aimed at fostering political and technical discussions on maternal and child health equity.

During the reporting period, the Bureau served as the technical secretariat for “A Promise Renewed for the Americas,” an interagency movement working to reduce the profound inequities in reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child, and adolescent health that persist in Latin America and the Caribbean. Work during the period included the identification of funding gaps and funding opportunities, the creation of a digital database for articles and documents on health inequalities, and a series of regional events aimed at fostering political and technical discussions on maternal and child health equity.

At the country level, the movement began a series of training workshops aimed at building capacity in ministries of health for measuring and monitoring health inequalities at the national and subnational levels.

Adolescent pregnancy has a major impact on maternal and child health and socioeconomic outcomes. These pregnancies increase the health risks for both mothers and children while reducing adolescent girls’ chances for education and future employment. PAHO has been a key actor in mobilizing strategic partnerships and actions to address this problem in Latin America and the Caribbean, which have among the highest adolescent fertility rates in the world (exceeded only by sub-Saharan Africa).

In 2014, the Council of Ministers of Health of Central America and the Dominican Republic (COMISCA) as well as the first ladies of Central America endorsed a subregional plan for preventing adolescent pregnancy, based on the outcomes of an international symposium spearheaded by the Bureau earlier in that same year. Priority areas include improving sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents, training health workers, promoting supportive legislative and policy environments, expanding and improving sex education, and encouraging youth participation. The Bureau is providing support for countries’ implementation of the plan.

PAHO’s Strategic Plan specifies four cross-cutting themes—gender, equity, human rights, and ethnicity—that are to be incorporated on a priority basis across the spectrum of the Organization’s technical cooperation. In December 2014, the Director established a new inter-programmatic working group responsible for facilitating this process. Its duties include ensuring that information relevant to these themes is shared across different departments and units, and designing and implementing initiatives to promote collaborative work in these areas. During the reporting period, the working group organized a training course for all PAHO staff on the social determinants of health in the context of the cross-cutting themes. Participants were encouraged to identify practical ways of incorporating these themes into their work, and the results were used to finalize a set of guidelines for mainstreaming the cross-cutting themes into the Organization’s work.

PAHO’s Strategic Plan specifies four cross-cutting themes—gender, equity, human rights, and ethnicity—that are to be incorporated on a priority basis across the spectrum of the Organization’s technical cooperation. In December 2014, the Director established a new inter-programmatic working group responsible for facilitating this process. Its duties include ensuring that information relevant to these themes is shared across different departments and units, and designing and implementing initiatives to promote collaborative work in these areas. During the reporting period, the working group organized a training course for all PAHO staff on the social determinants of health in the context of the cross-cutting themes. Participants were encouraged to identify practical ways of incorporating these themes into their work, and the results were used to finalize a set of guidelines for mainstreaming the cross-cutting themes into the Organization’s work.

In response to a mandate from PAHO’s 52nd Directing Council to address disparities in access to and use of health services by lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and trans (LGBT) people (Document CD52/18 [2013]), the Bureau organized the first-ever Regional Meeting on the Health of LGBT Persons and Human Rights in December 2014. Representatives of ministries of health, human rights organizations, universities, and civil society came together to discuss barriers to access for LGBT people to needed health services, as well as successful experiences in overcoming these barriers. Among other outcomes, the meeting produced recommendations for strategies and initiatives to collect and analyze data on how well health services in the Region are meeting the needs of the LGBT community.

In the area of gender and health, the Bureau completed a final evaluation of the 2009-2014 plan of action for PAHO’s Gender Equality Policy (Document CD54/INF/2 [2015]), based on self-assessments by 32 countries and territories. Key findings included:

PAHO’s work in disaster management seeks to increase the capacity of the health sector to prevent or reduce the health consequences of emergencies, disasters, and crises. In 2014, the Bureau provided technical cooperation and mobilized resources for disaster risk reduction, preparedness, and response in Latin America and the Caribbean. This included more than US$ 8.6 million in humanitarian assistance to meet the health needs of people affected by floods in Bolivia and Paraguay, drought and associated food shortages in Guatemala and Honduras, and severe weather in three Eastern Caribbean countries. The Bureau also continued to address the humanitarian needs of displaced populations in Colombia as well as the health recovery in Haiti.

PAHO’s work in disaster management seeks to increase the capacity of the health sector to prevent or reduce the health consequences of emergencies, disasters, and crises. In 2014, the Bureau provided technical cooperation and mobilized resources for disaster risk reduction, preparedness, and response in Latin America and the Caribbean. This included more than US$ 8.6 million in humanitarian assistance to meet the health needs of people affected by floods in Bolivia and Paraguay, drought and associated food shortages in Guatemala and Honduras, and severe weather in three Eastern Caribbean countries. The Bureau also continued to address the humanitarian needs of displaced populations in Colombia as well as the health recovery in Haiti.

During the period, PAHO continued to lead the mainstreaming of comprehensive disaster management in the health sector of CARICOM Member States. The Bureau contributed to the finalization of a subregional strategy and programming framework for 2014-2024 based on this approach, as well as an action plan and performance monitoring framework. The Bureau is also supporting the establishment of a new CARICOM Disaster Assessment and Coordination (CDAC) team that is intended to improve support for countries during emergencies and to better coordinate damage assessment and needs analysis. Training for CDAC team members began in May 2015, and the teams were expected to be operational by August 2015.

Bureau experts also supported the Eastern Caribbean Development Partners Group on Disaster Management, which facilitates coordination of external emergency assistance to Eastern Caribbean countries affected by major disasters. In February 2014, the Bureau participated in an after-action exercise to review the emergency response to heavy rains that affected Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in 2013.

The Bureau also strengthened its coordination with the 35 members of the Risk Emergency Disaster Working Group for Latin America and the Caribbean (REDLAC), coordinated by the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Bureau experts helped revise a training course on the new humanitarian architecture, led health-related sessions during international events to improve disaster response, and participated in efforts to improve inter-cluster and interagency coordination during emergencies.

In coordination with the Andean Health Organization (ORAS-CONHU), the Bureau continued its work with ministries of health in the Andean region to translate the strategic lines of the subregion’s Strategic Plan for Disaster Risk Management in the Health Sector (2013-2017) into action. During 2014, the Bureau supported the incorporation of the plan at the political level in the ministries of health of Ecuador and Chile; the organization of inter-country simulation exercises and drills for Peru and Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador, and Chile and Peru; and the development of cross-border emergency plans.

As part of its efforts to promote universal health and keep health high on the Region’s political agenda, the Bureau collaborated with the Joint Summit Working Group and Summit Implementation Review Group of the Organization of American States (OAS) on a “Mandates for Action” document prepared for the VII Summit of the Americas in Panama in April 2015. The Bureau provided technical inputs during discussions that led to a consensus among OAS Members States on eight health-related paragraphs that were included in the final document. The paragraphs supported priority health issues that included universal access to health and universal health coverage, disease outbreak and response and the International Health Regulations, NCDs, water and sanitation, food and nutrition, and maternal and child health.

As part of its efforts to promote universal health and keep health high on the Region’s political agenda, the Bureau collaborated with the Joint Summit Working Group and Summit Implementation Review Group of the Organization of American States (OAS) on a “Mandates for Action” document prepared for the VII Summit of the Americas in Panama in April 2015. The Bureau provided technical inputs during discussions that led to a consensus among OAS Members States on eight health-related paragraphs that were included in the final document. The paragraphs supported priority health issues that included universal access to health and universal health coverage, disease outbreak and response and the International Health Regulations, NCDs, water and sanitation, food and nutrition, and maternal and child health.

In related efforts, the Bureau contributed to the development of a new Inter-American Convention on the Human Rights of Older Persons. Through their participation in a special OAS working group, Bureau experts helped incorporate health-related issues of special relevance to older adults, including access to palliative care, human rights in long-term care services, preferential access to comprehensive health services, and legal mechanisms to guarantee informed consent and for explicit expression of preferences for end-of-life support. The convention was adopted by the OAS General Assembly in June 2015 and is the first international treaty on the rights of older adults.

During the reporting period, the Bureau continued its efforts to strengthen organizational efficiency, manage risks effectively, enhance transparency and accountability, and ensure ethics and fair treatment in the workplace.

An important development during the period was a new oversight initiative designed to improve the evaluation process within the Bureau. Historically, this process has suffered from a lack of coordination of the evaluation assignments that objectively review the performance and impact of programs and activities. A large share of this evaluation activity has been driven by external funding partners. Although evaluation reports have revealed important lessons for the Bureau, the findings have generally been limited to individual programs or specific country offices, with little sharing of lessons learned across the Bureau.

An important development during the period was a new oversight initiative designed to improve the evaluation process within the Bureau. Historically, this process has suffered from a lack of coordination of the evaluation assignments that objectively review the performance and impact of programs and activities. A large share of this evaluation activity has been driven by external funding partners. Although evaluation reports have revealed important lessons for the Bureau, the findings have generally been limited to individual programs or specific country offices, with little sharing of lessons learned across the Bureau.

In March 2015, the Bureau produced the first of a planned series of twice-yearly reports that will consolidate the major lessons learned from evaluation reports for dissemination across the Organization. The goal is to open the door to the use of evaluation assignments whose scope extends beyond individual programs or country offices, thereby nurturing ongoing improvements and decision-making processes of the Bureau and adding to both institutional memory and institutional development.

Also in the area of internal oversight, the Bureau hired an internal auditor in late 2014 to assess the risks and internal controls of the Mais Médicos program in Brazil. The auditor will perform four internal audit assignments annually on the program for its duration.

One of the most important internal developments during the reporting period was the implementation of key parts of the new PASB Management Information System (PMIS). This US$ 22.5 million initiative will modernize and improve support for the Bureau’s operations and technical cooperation. During the second half of 2014 and the first half of 2015, the project’s Human Capital Management module and payroll component (phase 1) were implemented, and implementation began of the system’s finance portion (phase 2, to be completed in early 2016). Phase 1 replaced many of the Bureau’s human resources legacy systems, while phase 2 will replace its core legacy financial systems: AmpesOmis, AMS/FMS (Award Management System/Financial Management System), FAMIS (Financial Accounting Management Information System), ADPICS (Advance Purchasing Inventory Control System), and SOS (Simplified Online Search). A number of other existing systems will continue to operate outside the scope of PMIS, including e-recruitment, taxes, pension, staff health insurance, and SharePoint.

One of the most important internal developments during the reporting period was the implementation of key parts of the new PASB Management Information System (PMIS). This US$ 22.5 million initiative will modernize and improve support for the Bureau’s operations and technical cooperation. During the second half of 2014 and the first half of 2015, the project’s Human Capital Management module and payroll component (phase 1) were implemented, and implementation began of the system’s finance portion (phase 2, to be completed in early 2016). Phase 1 replaced many of the Bureau’s human resources legacy systems, while phase 2 will replace its core legacy financial systems: AmpesOmis, AMS/FMS (Award Management System/Financial Management System), FAMIS (Financial Accounting Management Information System), ADPICS (Advance Purchasing Inventory Control System), and SOS (Simplified Online Search). A number of other existing systems will continue to operate outside the scope of PMIS, including e-recruitment, taxes, pension, staff health insurance, and SharePoint.

Formal PMIS training for staff began at Headquarters in November 2014 and continued through February 2015. A “Go Live Support Center” assisted staff during the rollout process, and lessons learned in phase 1 were documented to help improve functionality in phase 2. The PMIS project remains on budget and on time, and its planned full “go live” date remains as scheduled, for January 2016.