SUBMENU

Chagas disease is a parasitic, systemic, and chronic disease caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, with risk factors strongly link to low socioeconomic factors. Chagas disease is considered a neglected tropical disease. It is endemic in 21 countries in the Americas, although the migration of infected people can transport the disease to non-endemic countries of America and the world.

T. cruzi parasites are mainly transmitted to human by the infected feces of blood-sucking triatomine bugs, known as the "kissing bug". T. cruzi can infect several species of the triatomine bug, the majority of which are found in the Americas. A person becomes exposed when the infected insect deposits its feces in the person's skin when he or she is sleeping during the night. The person will scratch the infected area, unintentionally introducing the insect's feces in in the wounds of the skin, the eyes, or the mouth. Other modes of transmission are through blood transfusion, congenital, and organ transplants. Although mortality has significantly declined, the disease can cause irreversible and chronic consequences on the heart, digestive system, and nervous system.

- Chagas disease can be treated with Benznidazole and also Nifurtimox. Both medicines are almost 100% effective in curing the disease if given soon after infection at the onset of the acute phase.

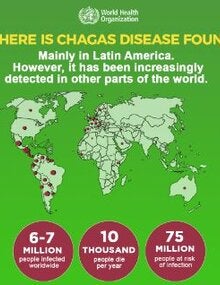

- Chagas disease is endemic in 21 countries in the Americas, and affects approximately 6 million people.

- In the Americas, Chagas disease show an annual incidence of 30,000 new cases average, 12,000 deaths per year, and approximately 9,000 newborns become infected during gestation.

- It is estimated that around 70 million people in the Americas live in areas of exposure and are at risk of contracting this disease.

Chagas disease is the most prevalent communicable tropical disease in Latin America. The most important vectors are the Triatoma infestans in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and Peru; the R. prolixus in Colombia, Venezuela and Central America; the T. dimidiata in Ecuador and Central America; and the Rhodnius pallescens in Panama.

Triatomine bugs can infect rodent, marsupials and other wild mammals. These triatomine bugs can also infect domesticated animals such as dogs and cat, and bring the T. cruzi (agent of the disease) inside human dwellings.

The T. cruzi parasites are mainly transmitted by the infected feces of blood-sucking triatomine bugs. These bugs typically found in the Americas, live in the cracks of poorly constructed homes in rural or suburban areas. Normally they hide during the day and become active at night when they feed on blood, including human blood. They usually bite an exposed area of skin or mucosa membranes (lips, conjunctiva, etc.), and the bug defecates close to the bite. The parasites enter the body when the person instinctively smears the bug feces into the bite, and contaminate the eyes, the mouth, or any lesion in the skin.

Although less common T. cruzi can also be transmitted through blood transfusions (20% if the cases) or organ transplant, vertically from an infected mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth (1% of the cases), and by the accidental ingestion of food contaminated with T. cruzi.

Chagas disease has two clinical forms or phases: an acute phase and a chronic phase. Many people (70- 80% of the infected) are asymptomatic all of their lives, while a 20-30% of the ones infected evolve into the chronic phase, which includes symptoms that indicate damages to the tissue of the heart, digestive system and/ or nerves system.

The acute phase, when it is symptomatic, lasts for about two months after infection. During the acute phase, a high number of parasites circulate in the blood.

Signs and Symptoms for acute Chagas disease can be absent or mild and include the following:

- Signs of entry of the parasite

- Rash and inflammatory nodules (Chagoma)

- Swelling of periorbital soft tissue (Romaña's sign)

- Fever

- Headache

- Nausea, diarrhea or vomiting

- Enlarged lymph glands

- Difficulty breathing

- Muscle, abdominal or chest pain

Although not typical, a first visible sign can be a skin chancre, called 'chagoma', or a purplish swelling of the lids of one eye. If the infection is left untreated, it can advance into the chronic phase.

A first visible signal can be a skin lesion, called "inoculation chagoma" a regional subcutaneous nodule with adenitis at the site of the bite; and in cases of ocular inoculation, very typical but rare (2% o f acute symptomatic cases) is possible to identify the "sign of Romagna" bipalpebral edema, with retroauricular adenitis. If the infection is not treated, it can progress to the chronic phase.

Over several years or even decades, Chagas disease affects the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system, the digestion system and the heart. Specific medical treatments and surgery may be necessary.

Signs and symptoms for chronic Chagas disease can include the following:

- About 30% of people will develop cardiac damage:

- Cardiomyopathy

- Heart rhythm abnormalities

- Apical aneurysm.

- Sudden death or heart failure caused by progressive destruction of the heart muscle.

- Less than 10% of patients will experience enlargement of the gastrointestinal tract and organs, and gastrointestinal motor disorders.

- Enlargement of the esophagus.

- Enlargement of the colon.

- Disturbances of gastric emptying.

- Colon and gallbladder motor disorders.

Chagas diagnosis is always clinical, epidemiological and based on laboratory testing (parasitology and serology).

During the acute phase, Chagas disease can be diagnosed through parasitological methods, given the large number of parasites circulating in the blood. In the acute stage, the studies focus on the search and recognition of Trypanosoma cruzi in direct examination and staining of blood smears (methodology: direct parasitological), and in determining the seropostivity of serology tests.

For chronic stage of the disease, Diagnosis is based on clinical assessment, serology and epidemiological history. The definitive diagnosis of T. cruzi infection depends on the positive result of at least two different serologic tests (ELISA, indirect immunofluorescence and indirect hemagglutination) that detect specific antibodies in patient sera.

There is no vaccine for the disease Chagas. Integrated vector control is the most effective method of preventing Chagas disease in Latin America, including chemical control by insecticides in infested homes, improvements in houses to prevent vector infestation, personal preventive measures such as bed nets, and informative education and communication to the community about vector-borne diseases.

Serological screening in blood donors is necessary to prevent infection through blood transfusion and organ transplant.

Chagas screening in pregnant women during prenatal care is needed to provide early diagnosis and treatment to newborns and other children of infected mothers.

Good hygiene practices in food preparation, transportation, storage and consumption; screening of blood donors; testing of organ, tissue or cell donors and receivers; and screening

Chagas disease may be etiologically treated in order to eliminate the infection T. cruzi with benznidazole or nifurtimox. If treatment was initiated during the acute phase, both drugs are effective in killing the parasite.

Every infected child should be treated.

Nevertheless, the efficacy of both drugs diminishes the longer a person has been infected, although all patients including chronic cases benefit from improved clinicopathologic changes if treated. Benznidazole and nifurtimox should not be taken by pregnant women.

The potential benefits of medication in chronic cases preventing or delaying the development of Chagas disease should be weighed against the long duration of treatment (up to 2 months), possible adverse reactions (occurring in up to 40% of treated patients), age, comorbidities, and other important characteristics of each patient.

The patients correctly diagnosed patients should receive further medical or surgical, pathophysiological or symptomatic, treatment, specific to each case.

Chagas disease is associated with multiple social and environmental factors that expose millions of people to infection. Among the main risk factors for Chagas disease are living in poorly constructed housing - particularly in rural and suburban areas - having limited resources, residing in areas of poverty that are socially or economically unstable or have high rates of migration, and belonging to groups linked to seasonal farm work and crop harvests. This disease contributes and perpetuates the cycle of poverty, reduces learning capacity, productivity, and the ability to generate income.

In the early 1990's, the countries affected by Chagas disease, especially those where the disease was endemic, were organized to combat this public health threat. Along with the Pan American Health Organization/ World Health Organization, country representatives generated a successful scheme for horizontal technical cooperation between countries, called the Sub-regional Initiatives for Prevention and Control of Chagas Disease. These initiatives have been developed in the Southern Cone (1992), Central America (1997), Andean countries (1998), Amazonian Countries (2003), and Mexico (2004). These countries have contributed in creating substantial improvements in the situation through the interruption of vector transmission in all or part of the territory of the affected countries, the elimination of exotic species of vectors, the introduction of universal screening of blood donors, the detection of congenital cases, the reduction of prevalence in children, reduction in morbidity, expansion of access to diagnosis and treatment, and improvement of the quality of diagnosis, clinical care, and treatment of infected and ill persons.

The initiatives in the Americas have helped achieve significant reductions in the number of acute cases of disease and the presence of domiciliary triatomine vectors in endemic areas. The estimated number of people infected with T. cruzi worldwide dropped from 30 million in 1990 to 6 to 8 million in 2010. In those 20 years, the annual incidence decreased from 700,000 to 28,000 new cases of infection and the burden of Chagas disease decreased from 2.8 million in 1990-2006 to disability-adjusted life years lost to less than half a million years.

While substantial progress has been made, not all countries have managed to achieve the goals that have been proposed. New challenges have emerged such as the spread of disease due to the migration of people living in endemic countries to non-endemic countries, the need to ensure the sustainability of programs, confronting the emergence or re-emergence of cases of Chagas disease, recovering from natural disasters, expanding coverage of diagnosis and treatment, and achieving universal access to treatment.

Geographical distribution of Chagas disease in the Americas according to the status of transmission by the main vector in each area. Year: 2011.

- Southern Cone. Interruption of vector transmission of T. cruzi by T. infestans and elimination of vector as a public health threat in Uruguay (1997-2012); interruption of vector transmission of T. cruzi by T. infestans in Chile (1999), Brazil (2006), Paraguay (Eastern Region, 2008, Alto Paraguay, 2013), Argentina (8 provinces between 2001 and 2013), and Bolivia (Department of La Paz and Dpto.de Potosí, 2011 - 2013).

- Central America. Interruption of vector transmission of T. cruzi by R. prolixus in Guatemala (2008), El Salvador (2010), Honduras (2010), Nicaragua (2010). Costa Rica (2010) and Belize (2010). Characterization of transmission from the sylvatic cycle in Panama (2013).

- Andean Region. Interruption of vector transmission of T. cruzi by T. infestans in Peru (Departments of Tacna and Moquegua) and by Rhodnius prolixus in 10 Municipalities in Casanare, Boyacá, Santander and Arauca in Colombia (2013).

- Amazon Region. Surveillance and prevention network in Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Guyana, French Guyana and Peru. Response to Chagas outbreaks of foodborne diseases.

- Mexico. Elimination of R. prolixus is certified in Chiapas and Oaxaca.

- Since the early 1990s, the countries affected by Chagas disease have organized to provide a public health response in conjunction with the PAHO/WHO, generating a successful horizontal technical cooperation scheme between countries, through Sub-regional Initiatives of Prevention and Control of Chagas Disease (Southern Cone, Central America-Mexico, Andean countries, and Amazonian countries).

- These countries have managed great achievements in controlling vector-borne transmission of T. cruzi including the interruption of vector-borne transmission in 17 affected countries and the elimination of certain species of vectors, implementation of universal screening of blood donors for Chagas disease in 21 endemic countries, increased coverage, and capacities of diagnosis and treatment of congenital cases of Chagas, expanded coverage of diagnosis and access to treatment, and clinical care of people infected and sick.

- El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico reached the elimination of Rhodnius prolixus as the main vector between 2009 and 2010, respectively. South America reached the elimination by T. infestans vector, in Brazil (Sao Paulo) and Uruguay, in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

- Through PAHO/WHO, the countries receive between 3,000 and 4,000 Nifurtimox treatments each year. Benznidazole, which is now produced in Argentina and Brazil, can be purchased through the PAHO/WHO Strategic Fund.

- The World Health Assembly 2010 resolution WHA 63.20 and PAHO/WHO 2010 resolution CD50.R17, establish and implement the current Strategy and Plan of Action for Chagas disease prevention, control, and care.

- PAHO/WHO 2009 resolution CD49.R19 and 2016 resolution CD55.R9 of Neglected Infectious Diseases, provide a frame of reference on controlling and eliminating Chagas disease as a public health problem.