Part III

Progress and challenges in the implementation of the Regional Strategy and Plan of Action on Adolescent and Youth Health, 2010-2018

III.1 Introduction

The Pan American Health Organization was established in 1902, and it consists of its Member States and the Secretariat. As stated in its Constitution, PAHO’s purpose is to promote and coordinate efforts of the countries of the Western Hemisphere to combat disease, lengthen life, and promote the physical and mental health of the people (132). Among the important tools used to express and galvanize this collective commitment are resolutions that articulate the commitments, roles, and responsibilities of the Member States and the Secretariat towards specific health goals and issues.

In 2008, PAHO Member States adopted the Regional Strategy for Improving Adolescent and Youth Health (Resolution CD48.R5) (4). The vision of the Regional Strategy is that adolescents and youth in the Region of the Americas lead healthy and productive lives. The overarching goal is to contribute to the improvement of the health of young people, by developing and strengthening an integrated health sector response and implementing effective adolescent and youth health promotion, prevention, and care programs. A year later, in 2009, PAHO Member States adopted the Plan of Action on Adolescent and Youth Health (Resolution CD49.R14), with the aim of operationalizing the Regional Strategy over the 2010-2018 period (4). Both the Regional Strategy and the Plan of Action were innovative in a number of ways. First, they called for intersectoral action based on seven strategic areas that have a crosscutting impact on a range of priority health problems that affect adolescents and youth in the Region (Box III.1). For each strategic area there were clear objectives, indicators, and recommended actions on the interagency, regional, subregional, and country level.

In addition to the seven strategic areas (Box III.1), the Plan of Action proposed eight health goals, with 19 targets (Annex II.A), to help quantify and monitor the initiative’s impact on the regional and country levels (4). Part II of this report provides an overview of the health status of adolescents and youth based on these goals and targets.

The following sections of the report provide an overview of the implementation of the Plan of Action since its approval. Considering the wide scope of the initiative—relating to all areas of PAHO’s technical cooperation, and having multiple levels of implementation, on regional, subregional, and country levels—this overview does not intend to be exhaustive. Instead, it aims to highlight key actions taken, some by PAHO, and others in coordination with partners such as the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Bank.

Box III.1: Strategic areas for action on adolescent and youth health

- Strategic information and innovation: Strengthen the capacity of the countries to generate, use, and share quality health information on adolescent and youth health and their social determinants, including by disaggregating information by age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level.

- Enabling environments for health and development using evidence-based policies: Promote and secure the existence of environments that enable adolescent and youth health and development through the implementation of effective, comprehensive, sustainable, evidence-informed policies, including legal frameworks and regulations.

- Integrated and comprehensive health systems and services: Improve comprehensive and integrated quality health systems and services to respond to adolescent and youth needs, with emphasis on primary health care.

- Human resources capacity-building: Support the development and strengthening of human resources training programs in comprehensive adolescent and youth health, especially those in the health sciences and related fields, in order to improve the quality of adolescent and youth health promotion, prevention, and care policies and programs.

- Family, community, and school-based interventions: In alignment with PAHO’s 2009 Family and Community Health concept paper, develop and support adolescent and youth health promotion and prevention programs, incorporating community-based interventions that strengthen families, involve schools, and encourage broad-based participation.

- Strategic alliances and collaboration with other sectors: Facilitate dialogue and alliance-building between strategic partners to advance a regional adolescent and youth health agenda and to ensure that strategic partners participate in the establishment of effective policies and programs for this age group.

- Social communication and media involvement: Support the inclusion of social communication interventions, using traditional media and innovative technologies to promote adolescent and youth health in national adolescent and youth health programs.

Source: (4).

III.2 Strategic information and innovation

The objective of this action area is to strengthen the capacity of the countries to generate quality health information on adolescent and youth health and their social determinants, disaggregating information by age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level, through:

reaching consensus on a list of basic indicators that facilitate the identification of gaps and inequities in adolescent and youth health

building capacity for: a) development of national adolescent health information systems; b) monitoring and evaluation of the quality, coverage, and cost of national adolescent and youth health programs and services; and c) aligning efforts with other relevant work on this topic in PAHO and on the global level

promoting the analysis, synthesis, and dissemination of integrated information from different data sources on the state of adolescent and youth health and their determinants

supporting regional and national research on the impact of new and innovative methods to improve the health and development of young people, and to disseminate effective interventions and best practices

The list of indicators included in the Regional Strategy and the Plan of Action for 2010–2018 (4) was generated through a consultative regional process. The indicators were selected based on the following criteria: 1) they represented critical health outcomes or contributing behaviors for adolescents and youth and 2) national-level data were already available or could be generated. The plan called for disaggregated reporting of these indicators by sex, five-year age group brackets, and, where possible, socioeconomic characteristics, ethnic group, and other relevant stratifiers. In addition to creating the indicator list, the following key actions were taken to support the generation and improvement of the quality of health information on adolescent and youth health:

Maintenance of the PAHO mortality database and publicly accessible portal, and inclusion of the adolescent (10-19 years) and youth (15-24 years) age categories in the portal. The PAHO Health Information and Analysis Unit coordinates the collection, cleaning, standardization, and publication of mortality data reported by the PAHO Member States. The information is made accessible through the Web-based mortality portal (39). Through this portal, interested persons can access adolescent and youth mortality data disaggregated by sex for their own country and for other countries, as well as regional rates. Mortality reporting by countries tends to lag by two to three years. In addition, some countries have significant percentages of ill-defined mortality cases, which lowers the quality of the mortality rates. The relevant PAHO departments and units provide ongoing technical cooperation to the Member States to improve the quality and timeliness of mortality reporting.

Adolescent health surveys. A significant portion of the data required for monitoring of the mentioned set of indicators is generated through surveys. In partnership with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and WHO, the Secretariat provides ongoing support to countries to implement two standardized global adolescent health surveys, the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS) (81) and the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS). The GSHS methodology allows for low-cost collection of data on behavioral risk factors and protective factors in 10 key areas among young people aged 13 to 17 years, through a school-based, self-administered survey. Among the topics that countries can include in their survey are sexual behaviors, mental health and substance use, hygiene, dietary behaviors and physical activity, violence and unintentional injury, and protective factors. On average, between 5 and 10 countries from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are supported each year to implement these surveys. Between 2008 and 2014, 23 countries in the Americas completed at least one GSHS, and 3 countries completed two. In addition to these global surveys, support has also been provided to countries to conduct national adolescent and youth health studies. For example, six Overseas Caribbean Territories (OCTs) (Aruba, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat, Saint Eustatius, and Sint Maarten) were supported during 2010-2012 to implement school-based adolescent health and sexuality surveys (80).

The Adolescent Information System: The Adolescent Information System (Sistema Informático del Adolescente (SIA)) was developed by the Latin American Center for Perinatology, Women and Reproductive Health (CLAP) in response to the need to improve the quality of adolescent care in health services, by applying an integrated approach (133). The SIA consists of a basic adolescent medical record form and a follow-up form. These forms are applicable to encounters with professionals from several disciplines, including—but not limited to—medical care, social services, nursing, and psychology. The SIA facilitates a comprehensive assessment of the health and social situation of the adolescent, beyond the primary reason for the encounter. The form includes a range of variables related to personal history, family history, and the physical examination. Beyond its use in individual encounters, analysis of compiled SIA data generates important information of public health significance. Countries that include Argentina, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Uruguay have adopted the SIA, with varying scopes.

The Perinatal Information System: The Perinatal Information System (SIP) is a standard for perinatal clinical records developed by PAHO/WHO at CLAP. While not specifically geared towards adolescents, SIP can generate data on the perinatal health of adolescents, including on the profile of pregnant adolescents, their care-seeking behavior, and their birth outcomes. This information can inform strategic actions to address these issues.

The adolescent health portal: To improve country access to adolescent health information, PAHO developed an adolescent health portal in 2012. It served as an interactive tool, where PAHO and countries could enter or update their information and also generate graphs, figures, and country profiles. Countries actively used this tool for several years, even though there were challenges in maintaining and regularly updating the country information. The adolescent health portal is currently inactive. Its functions are being incorporated into a new integrated health information platform under construction at PAHO.

Capacity-building: Technical cooperation provides for strengthening of country capacity to generate and use quality information on adolescent and youth health. These efforts have included several sensitization and training workshops, as well as direct support to countries for development of monitoring and evaluation frameworks for their national plans and programs.

Research: In 2009, PAHO commissioned a multicountry study with the aim of generating information on the sexual and reproductive health of indigenous youth. The study was implemented in Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Peru, and resulted in recommendations to sexual and reproductive health services for indigenous youth in these countries (134). In general, while PAHO’s direct involvement in research has been limited, PAHO continues to have an important role in the formulation of the regional research agenda through the close working relationships with academic institutions. These include the Catholic University of Chile, the Johns Hopkins University, Iowa State University, and the University of the West Indies.

Inequity analysis: A Promise Renewed for the Americas (APR-LAC) was established in 2013 as an interagency movement that sought to bring more attention to health inequalities affecting women and children in Latin America and the Caribbean, with the Secretariat based at PAHO. Through this area of work, PAHO and its regional partners provided capacity-building and technical support for quantitative and qualitative inequity analysis based on the measurement and monitoring of health inequalities. In 2017, the APR-LAC initiative transitioned to become Every Woman Every Child Latin America and the Caribbean (EWEC-LAC), the regional interagency coordinating mechanism for the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health in Latin America and the Caribbean, for which a primary goal continues to be analyzing and addressing inequities in health.

Overall, the capacity of PAHO Member States to generate strategic information has been strengthened through the development of various tools and mechanisms and through PAHO’s provision of technical support to countries. However, the availability of timely and reliable data on the health of adolescents and youth remains a challenge, and continued efforts are essential. Moving forward, there must be an emphasis on strengthening country capacity to routinely generate national and subnational adolescent and youth health data that is disaggregated by five-year age groups, sex, ethnicity, educational status, wealth quintile, urban/rural, and other relevant variables. Inequity analysis is critical for identifying vulnerable and underserved groups, as well as the factors contributing to their conditions of vulnerability.

III.3 Enabling environments for adolescent and youth health and development using evidence-based policies

The objective of this action area is to promote and secure the development of enabling environments and the implementation of effective, comprehensive, sustainable, evidence-based policies on adolescent and youth health, through:

- establishing public policies that support a better state of health for young people and guarantee specific budget allocations for adolescent and youth health

- developing, implementing, and complying with evidence-based policies and programs in a manner consistent with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and other UN and inter-American system human rights instruments

- advocating for environments that promote health and development of young people, considering social determinants of health and the promotion of health and secure communities, including the Healthy Schools Initiative

- supporting the development and/or revision of current policies and legislation on priority health topics for young people, especially those that have impact on health services access

Key interventions implemented under this action area have included:

Support to Member States to develop and update national adolescent and youth health policies, strategies, and plans: By the end of 2015, 30 out of 35 PAHO Member States (86%) and 7 out of 13 Associate Members and Dutch and British Overseas Territories had established adolescent health objectives in national adolescent health policies, strategies, or plans, either as part of their health plans or in separate adolescent health strategies or plans. In total, 77% of the Member States, Associate Members, and Overseas Territories had established adolescent health objectives (135). Moreover, several countries developed thematic plans and strategies related to specific health issues, such as national adolescent pregnancy prevention plans. A PAHO review of the plans and strategies found that the majority of these strategies and plans focused on adolescents in the age group 15-19 years, with limited attention for adolescents aged 10-14 years and for youth aged 20-24. Annex III.A provides an overview of national adolescent and youth policies, plans, and strategies reported to PAHO in 2017. Several of these strategies and plans have expired, or are close to expiration, which creates a window of opportunity for updating in line with the SDGs and the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescent Health. Annex III.B summarizes information concerning budget allocations for adolescent health activities, reported to WHO by 26 LAC countries during the period 2010-2016. Together, those two annexes show that some countries either lack adolescent health strategies or plans or do not have a dedicated budget for their implementation. Annex III.C reports on the issues for which adolescents are a specific target group in the national policies, strategies, and plans of these 26 countries. Annex III.B and Annex III.C drew from an online dashboard developed by WHO that provides access to all country reports on the global maternal, newborn child, and adolescent policy indicator surveys (136).

Promote and foster a supportive legal and policy environment for the health of young persons in a manner consistent with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the concluding observations on adolescent health issued by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child: As the health agency of the inter-American system, PAHO is in a unique position to provide the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the UN treaty bodies with technical opinions and relevant information on promoting and protecting young persons’ right to the highest attainable standard of health. Some of the work conducted by PAHO in this area includes strengthening the legislative and judicial branches by using human rights instruments, technical guidelines, and strategic information on the legal capacity of adolescents and adolescent health, including their sexual and reproductive health and rights. This has been done through regional, subregional, and country-level workshops; generation of strategic information (137); and ongoing dialogue. An important strategy has been to foster dialogue on these issues among health care providers, policymakers, decision-makers, judges, legislators, national human rights commissions, ombudspersons, and civil society. These experiences have shown that many of these persons and entities continue to have very limited information about human rights obligations and mechanisms to protect the health and well-being of young people. This is true for young persons in general, and specifically for those with diverse gender identities, expressions, and sexual orientation, with regard to their access to health services, goods, facilities, and information crucial to making decisions. Information that 26 LAC countries have reported to WHO through the global maternal, newborn child, and adolescent policy indicator surveys (Annex III.D) points to continuing legal barriers for adolescents seeking health services (136).

Support the development and revision of national legislation: In recognition of PAHO’s expertise, countries have been requesting support for developing and reviewing legislation. PAHO has provided that assistance on an ongoing basis, using human rights instruments such as conventions, protocols, declarations, and standards as the basis for review.

According to the available information, the majority of countries in the Region have developed governance documents related to adolescent health, in the form of legislation, policy, strategies, and plans. However, the policies, plans and strategies tend to focus on the age group 15-19 years, with limited attention for adolescents aged 10-14 years, and for youth aged 20-24 years, while this latter age group is also included in the age range of the Regional Strategy. The lack of budget allocations in some countries raises concerns about the feasibility of implementing the strategies and plans. In addition, significant legal barriers persist for adolescents seeking access to comprehensive health services.

III.4 Integrated and comprehensive health systems and services

The objective of this action area is to bolster the capacity of health care systems to respond to adolescent and youth needs. For this, there must be a focus on strengthening primary-level promotion, prevention, and care services and on supporting the effective extension of social protection through:

- implementing effective interventions utilizing the Integrated Management of Adolescent Needs (IMAN) model

- integrating services with referrals and counter-referrals among the primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels

- increasing access to quality health services by developing minimum standards of care and by ensuring availability of critical public health supplies

- developing models of care, including alternative and innovative service provision (e.g., mobile clinics, health services linked to schools and pharmacies)

- conducting studies on the availability, utilization, and cost of services

Box III.2: The carné de salud adolescente (adolescent health card) in Uruguay

The adolescent health card was developed in 2009 by ministerial decree, with technical support from PAHO, and updated in 2017 in a collaborative effort with adolescents, according to the PAHO Uruguay Country Office. The main purpose of the card is to mobilize, empower, and engage adolescents in their health. It contains health records (e.g., vaccinations, growth, weight), provides health tips, and links adolescents with other resources, including websites for additional information and services. Adolescents show the card when accessing health services, and it must also be presented to the school each academic year.

Source: (4).

Various key activities have been implemented under this action area. Three examples of these efforts are:

- Expansion and country-level adaptation of the IMAN model: The IMAN model was introduced by PAHO prior to the current Regional Strategy on adolescent health, as a model for comprehensive adolescent health services. Based on this approach, PAHO and UNFPA developed a module on adolescent sexual and reproductive health (138), and, in 2012, PAHO coordinated the development of a module on adolescents and noncommunicable diseases (139). Various IMAN training workshops were implemented on the regional, subregional, and country level, and the IMAN approach has been widely adopted in the Region, resulting in the incorporation of this approach in national guidelines and manuals of several countries (140).

- Definition of a package and national standards for adolescent health services: Based on WHO normative guidance and the IMAN model, technical cooperation was provided to countries to define a comprehensive package of adolescent health services and to develop standards for those services. The ultimate aim was to improve access for adolescents to quality health services that respond to their specific needs (Annex III.E). WHO’s publication of Global Standards for Quality Health Care Services for Adolescents in 2015 provided a new impetus for countries to develop or update standards for adolescent health services (141).

- Incorporation of adolescents and youth in the regional universal health agenda: In September 2014, PAHO Member States approved the Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage (Resolution CD53.R14) (5). In this declaration, Member States resolved to move toward providing universal access to comprehensive, quality, progressively expanded health services that are consistent with health needs, system capacities, and the national context. They also resolved to identify the unmet and differentiated needs of the population, as well as specific needs of groups in conditions of vulnerability. Key pillars of the regional universal health agenda include improving governance and human resource capacity; increasing efficiency and public financing of health; and empowering people and communities. This is to be done through training, active participation, and access to information for community members. This is so that those persons know their rights and responsibilities, and so that they can take an active role in policy-making; in actions to identify and address health inequities and the social determinants of health; and in health promotion and protection. Through inclusion of adolescents and their health needs in the regional and country-level dialogue, structural actions can be promoted so that adolescents and youth have increased, sustainable access to quality health services.

III.5 Human resources capacity-building

The objective of this action area is to support the development and strengthening of comprehensive adolescent and youth health human resources training programs. The priority is to be on health sciences and related fields, but with inclusion of school teachers, community health promoters, and others who can participate in multidisciplinary teams to respond to the health and development needs of young people. This is to be done through:

- developing and implementing adolescent and youth health and development training programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and for in-service professionals, utilizing new technologies such as e-learning platforms

- including the topic of adolescent and youth health in academic curricula for students enrolled in health and/or education programs at the graduate and postgraduate level

- advocating for building the capacity of primary health care providers, using evaluated courses in comprehensive adolescent and youth health that are supported by PAHO and that are currently available on diverse e-learning platforms

- incorporating current scientific evidence on young people, as well as training on program monitoring and evaluation, in available e-learning courses and other virtual platforms

This action area may well have been the most heavily invested area of the Regional Strategy on adolescent and youth health in recent years. The Secretariat has organized more than 40 regional, subregional, and country-level capacity-building workshops on topics related to adolescent health. These have been for a range of stakeholders, including adolescent health program managers, health care providers, youth, legislators, human rights advocates, and other stakeholders. Four key areas of the capacity-building efforts are described below.

Scholarship program for postgraduate adolescent health training

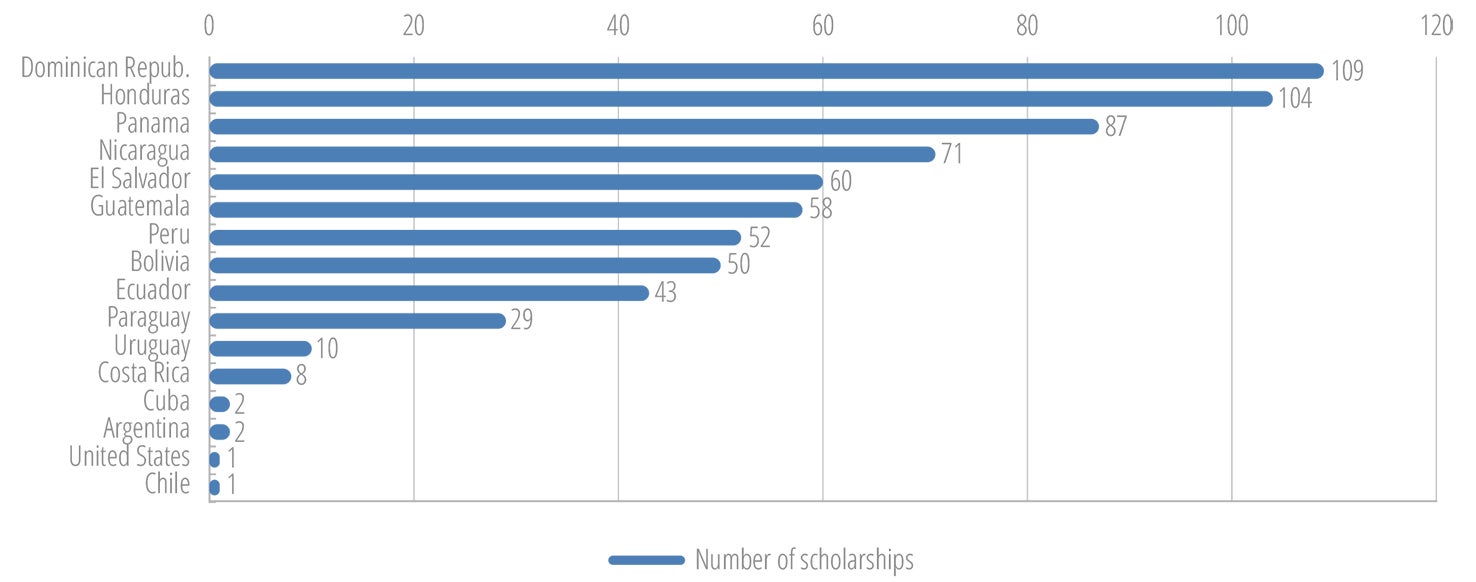

In 2003, PAHO entered into a partnership with the School of Medicine of the Catholic University of Chile for the development of a diploma course on adolescent health. The modular course is offered as postgraduate training through a virtual platform, over a nine-month period. It is open to a wide range of health professionals, including physicians, nurses, mental health specialists, social workers, and others involved in adolescent health programs and services. To facilitate optimal participation of stakeholders in this course, PAHO established a scholarship program, which offers tuition at a discounted price. During 2015-2016, PAHO conducted an evaluation of the scholarship program, in partnership with the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. The evaluation indicated that PAHO provided 687 scholarships to countries during the period 2006-2015, including 442 since the adoption of the regional Plan of Action. Candidates were jointly selected by the national authorities and the PAHO country offices. The Dominican Republic (109), Honduras (104), Panama (87), and Nicaragua (71) had the highest number of scholarship recipients (Figure III.1).

Just over three-quarters of the scholarship recipients were females. The course participants consisted of general physicians and specialists, psychologists, nurses, and other care providers. At the time of their participation, all the scholarship recipients were involved in adolescent health programs or services, on a managerial level or in direct service delivery.

All the scholarship recipients were invited to participate in an online survey that asked if the course had helped improve their proficiency in adolescent health and development, in general domains and specific competencies as defined by WHO (142). On a scale of 1 (least) to 10 (greatest), the 282 survey respondents rated their improvement in the various competencies as being between 6.7 and 8.2. They gave the highest improvement score to competency 3.5, “provide sexual and reproductive health care” (Table III.1).

| Domain/ Competency number | Description of domain/competency | Improvement rating |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1 | Basic concepts in adolescent health and development, and effective communication | |

| 1.1 | Demonstrate an understanding of normal adolescent development, its impact on health, and its implications for health care and health promotion | 7.4 |

| 1.2 | Effectively interact with an adolescent client | 7.5 |

| Domain 2 | Laws, policies, and quality standards | |

| 2.1 | Apply in clinical practice the laws and policies that affect adolescent health-care provision | 7.4 |

| 2.2 | Deliver services for adolescents in line with quality standards | 7.4 |

| Domain 3 | Clinical care of adolescents with specific conditions | |

| 3.1 | Assess normal growth and pubertal development, and manage disorders of growth and puberty | 7.2 |

| 3.2 | Provide immunizations | 7.1 |

| 3.3 | Manage common health conditions during adolescence | 7.8 |

| 3.4 | Assess mental health and manage mental health problems | 7.1 |

| 3.5 | Provide sexual and reproductive health care | 8.2 |

| 3.6 | Provide HIV prevention, detection, management, and care services | 8.0 |

| 3.7 | Promote physical activity | 7.7 |

| 3.8 | Assess nutritional status and manage nutrition-related disorders | 7.4 |

| 3.9 | Manage chronic health conditions, including disability | 6.7 |

| 3.10 | Assess and manage substance use and substance-use disorders | 7.2 |

| 3.11 | Detect violence and provide first-line support to the victim | 7.7 |

| 3.12 | Prevent and manage unintended injuries | 6.7 |

| 3.13 | Detect and manage endemic diseases | 7.1 |

The evaluation indicates that the scholarship program substantially improved adolescent health core competencies among health care providers in the Region of the Americas.

Inclusion of adolescent content in curricula of training programs for health and related professions

PAHO collaborated with various universities in the Region, including the Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and universities in Argentina, Guatemala, Mexico, and Venezuela, in developing adolescent health content and courses. More recently, in 2015, PAHO entered into a partnership with the University of the West Indies (UWI) for the development of adolescent health training programs at the Faculty of Medical Sciences and the Open Campus.

PAHO Virtual Campus

The Virtual Campus of Public Health is a PAHO technical cooperation tool that provides a range of self-learning and tutored courses that are free to all (143). Several of the courses offered through the Virtual Campus are pertinent to adolescent and youth health, including health and human rights, oral health, gender and health, and tobacco and alcohol use prevention courses. Because of the virtual nature of the platform, it can provide learning opportunities at low cost to all stakeholders who have access to internet.

Training workshops

An integral component of PAHO’s technical cooperation strategy is the regular organization of in-person workshops and training events for regional and country-level stakeholders on specific topics related to adolescent and youth health. In addition, adolescent health training has been provided for other stakeholder groups, including NGOs and youth themselves, in order to facilitate and foster their engagement in dialogue, programs, and services related to the health of adolescents and youth.

There is a high level of turnover of health care providers and program managers in most countries, as well as a lack of regular adolescent-specific training available for health care providers on the country level (Annex III.E). Given that, it is essential to have ongoing investment in pre- and in-service training for health care providers and related professions, policymakers, and other government officials, in order to ensure a critical mass of knowledge and skills to adequately address adolescent and youth health issues.

III.6 Family, community, and school-based interventions

The objective of this action area is to develop and support adolescent and youth health promotion and prevention programs through community-based interventions that strengthen families, involve schools, and encourage broad-based participation, through:

- developing and disseminating evidence-based tools that help strategic actors carry out interventions to strengthen the family

- encouraging community mobilization efforts to modify institutional policies and foster supportive environments for the health and development of young people

- developing tools to promote the empowerment of adolescents and youth and facilitate their meaningful participation in the communities where they live

- strengthening cohesion between the health and education sectors in the development, monitoring, and evaluation of comprehensive programs for adolescents and youth

There is compelling evidence that the health and development of young people are profoundly affected by the relationships they have with parents, peers, their school, and their communities (6, 144, 145). Studies have noted significant associations between low levels of connectedness or emotional attachment with the family, peers, school, and community and increased risk of negative health outcomes and behaviors, such as anxiety, depression, suicide ideation and attempts, unsafe sex, unplanned pregnancy, and substance use (144, 145). In contrast, positive relationships and high levels of connectedness can promote emotional and physical well-being, and protect adolescents from engaging in behaviors that may compromise their health in the short, medium, and long term (6, 144, 145).

In recent years, PAHO has introduced several model approaches and interventions that aim to engage the family, the school, and the community in the promotion and protection of the health and wellness of young people. These activities have included:

Familias Fuertes – Amor y Límites (Strengthening Families - Love and Limits): In 2000, PAHO entered into a partnership with the Human Sciences Extension and Outreach program of Iowa State University (ISU HSEO) to implement their Strengthening Families Program 10-14 (SFP 10-14) (146) in Latin America. The program is an evidence-based family life skills training curriculum for adolescents and their parents. It is designed to reduce risk-seeking behaviors, delinquency, and alcohol and drug abuse among adolescents; foster positive adolescent-parent relationships; and improve the social competencies and school performance of adolescents. It promotes parental skills and better communication in families, in order to reduce behavioral risk factors for adolescents. The program consists of seven weekly two-hour sessions with 6 to 12 participating families, led by trained facilitators. In an agreement with ISU HSEO, PAHO translated the package into Spanish and also invested in a review process with Latin American countries, resulting in a version adapted for Latin America, called Familias Fuertes – Amor y Límites (Strong Families – Love and Limits). To date, this program has been introduced in all Latin American countries and implemented with varying scopes. In several countries, including Colombia and Peru (Box III.3), the program has been formally adopted by the national authorities as a core national strategy for the promotion of child and adolescent health. In 2016, PAHO commissioned the Johns Hopkins University to conduct an external evaluation of the implementation and impact of the Familias Fuertes program, to inform continued implementation of this approach in the Region.

Box III.3: Familias Fuertes in Peru

In Peru, implementation of the Familias Fuertes program started in 2005, with training of the first cohort of facilitators. That was followed by the first application of the program in 2007 in nine municipalities of the Lima Metropolitan Area, coordinated by PAHO. In 2008 the program was transferred to the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA), through a collaborative agreement. Since then, DEVIDA has been coordinating the implementation of Familias Fuertes, and the program was incorporated in the regular programming and budget of DEVIDA. Currently, Familias Fuertes is being implemented in 23 regions of Peru, through the regional education directorates. The program has continued to expand. DEVIDA has trained 8,338 facilitators nationwide, and has reached more than 120,000 families with this intervention. DEVIDA has also provided support to other countries, including Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Paraguay, for training of facilitators.

Source: National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA).

Health-Promoting Schools: The Health-Promoting Schools Regional Initiative was started in the early 1990s. Supported by PAHO, the OAS, and the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Initiative aims to provide a healthy school environment for living, learning, and working. The purpose of the program is to form future generations with the necessary knowledge, abilities, and skills for promoting and caring for their health, the health of their family, and the health of their community. As a result of the Initiative, the majority of the countries in the Region have developed healthy schools efforts, some with a focus on the preschool level and others at the primary or secondary school level. School-based health promotion activities continue to be implemented and supported in several countries in the Region.

Mainstreaming human security in adolescent and youth health plans: The human security approach addresses the social determinants of health at the local level, seeks the establishment of power-sharing governance for health, and promotes self-reliance and self-determination among individuals and communities (147). In particular, the human security approach addresses the linkages among freedom from fear, freedom from want, and freedom to live in dignity; focuses on the ways in which people experience vulnerability in their daily lives and acknowledge that different threats feed off one another and thus need to be addressed in a comprehensive manner; is people-centered and context-specific; includes all relevant sectors and actors in the planning, decision-making, and implementation processes; focuses on promotion and prevention to the extent possible; and creates synergy between protection and empowerment actions. Mainstreaming the human security approach in adolescent and youth health plans adds value to PAHO’s regional adolescent and youth health agenda by injecting the promotion of individual and community resilience into the process. In particular, it can guide stakeholders to be better prepared in the face of health threats so that they can bounce back more quickly and emerge stronger from these threats at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination.

Other interventions: Several other model interventions aimed at improving the health and wellness of adolescents have been launched in recent years, but their implementation has remained limited, often confined to specific time-bound funding. These efforts have included:

Aventuras inesperadas: Aventuras inesperadas (Unexpected Adventures) is a peer-driven multimedia program that aims to train peer educators to promote healthy development among their contemporaries. It has been implemented in selected countries. The main principles of this program are that adolescence is a fascinating time, that each change in the body or the soul brings new experiences and new responsibilities, and that, together, these things make adolescence a great adventure.

Escuelas de fútbol jugados por la salud: Escuelas de fútbol jugados por la salud (Schools of Soccer Played for Health) is a health promotion program aimed at males in the age group 8-12 years. Using soccer to promote gender equality and nonviolence, the program has been implemented in 20 countries, supported with funding from the Johan Cruyff Foundation.

TEACH-VIP Youth: This initiative aims to foster alliances between adults and youth for the prevention of youth violence. The intervention consists of a training program for adults and youth to plan, implement, and evaluate programs in their communities to prevent youth violence.

Arte, salud y desarrollo: In recognition of the important role that art can play in promoting health and positive development, PAHO worked in partnership with a network of Latin American artists to organize an international forum titled “Arte, Puente para la Salud y el Desarrollo” (Art, Bridge for Health and Development). The event participants reached agreement on the Declaration of Lima on art, health, and development. Consequently, art and health initiatives were implemented in various countries, at varying scopes.

Youth participation and empowerment

Youth participation and empowerment has been and continues to be a cross-cutting effort in PAHO’s technical cooperation, with special emphasis on empowering adolescent girls. These efforts have included inviting young people to participate in and contribute to strategic meetings and activities targeting young persons, as well as seeking their input on specific topics through surveys, social media activities, and other means. In 2010, PAHO published a strategic document titled “Empowerment of Adolescent Girls: A Key Process for Achieving the Millennium Development Goals.” That publication advocated persuasively for and provided practical recommendations for empowering adolescent girls, as a critical element of sustainable human development (148). In addition, PAHO invested in working with, and empowering indigenous and Afro-descendant youth networks, engaging them in dialogue around their health priorities and challenges. The work with these networks has illustrated the critical importance of meaningful participation of young people in the design and implementation of health interventions.

III.7 Strategic alliances and collaboration with other sectors

The objective of this action area is to facilitate dialogue and alliance-building between strategic partners in order to advance the adolescent and youth health agenda, and to ensure that key actors participate in the development of policies and programs for this age group. This can be done through:

- developing integrated and coordinated actions between the health sector and strategic partners at the regional, national, and local levels, in such areas as education, the judiciary, labor, public security, housing, and the environment

- increasing and strengthening adolescent and youth interagency programs supported by the UN and by entities of the inter-American system

- establishing mechanisms for South-South cooperation and for sharing of best practices and lessons learned in the Region

Key actions taken by PAHO under this action area have included:

Multisectoral stakeholder engagement: Increasingly, PAHO is engaging a multisectoral group of stakeholders in regional and subregional activities related to the health of adolescents and youth, in order to provide a platform for intersectoral exchange and articulation. This has been especially true for the education sector and for stakeholders with responsibility for gender mainstreaming, human rights, and social protection.

Regional partnerships: Strategic ongoing partnerships exist among PAHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), UNESCO, the World Bank, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), and other relevant partners and stakeholders to facilitate dialogue, joint action, and alignment of programs and activities. PAHO also works closely with the Council of Ministers of Health of Central America (COMISCA), the Andean Health System - Hipólito Unanue Convention (ORAS - CONHU), and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) on the implementation of their respective subregional plans for the prevention of adolescent pregnancy and for other areas of adolescent health.

III.8 Social communication and media involvement

The objective of this action area is to support the inclusion of social communication interventions and innovative technologies in national adolescent and youth health programs, through:

- promoting positive images, values, and behaviors regarding adolescent and youth health

- strengthening the capacity of Member States to use social communication techniques and new technologies effectively to increase access to health interventions and services

- supporting the generation of evidence on this topic, especially in the use of new technologies and their impact on health.

Key activities under this action area include:

Inclusion and presentation of positive images of adolescents and youth in PAHO publications: PAHO has been consistent and selective in the inclusion of positive, respectful images of adolescents and youth in all publications.

Promotion of and capacity-building in the use of digital media in adolescent health: PAHO established a collaborative partnership with a California-based NGO, YTH (youth+tech+health), whose main goal is to enhance youth health and wellness through technology. Each year, YTH organizes an international conference for trailblazing technology that advances youth health and wellness. The event brings together innovators in youth advocacy, health, and technology to showcase what works, share ideas and learnings, and launch new collaborations. PAHO and YTH have collaborated in the organization of two regional workshops on the use of digital technology in adolescent health, and also in developing digital health strategies in several countries, including Guatemala and Suriname.

Commemoration of advocacy days, such as International Youth Day and International Day of the Girl Child: The implementation of targeted outreach events during these occasions provided the opportunity for advocacy and information-sharing on topics related to the health of adolescents and youth.

Conclusion

The information provided in this part of the report highlights significant progress in the regional and country-level adolescent and youth health response. The development of national policies, strategies, and plans, facilitated the articulation and institutionalization of national adolescent and youth health programs in most countries. However, the lack of assignment of human and financial resources limited the implementation of these strategies and plans. Review of the national strategies and plans also indicated limited articulation of approaches to identify and reach subgroups of young people living in conditions of vulnerability.

Several promising interventions were introduced in countries, however, with a few exceptions, these were not taken to the scale necessary to achieve significant results. The lack of systematic monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of initiatives also compromised the ability at regional and country level, to determine what works in the context of the Region. Major investments were made in capacity-building of different cadres of stakeholders in a range of adolescent health topics; however, the lack of M&E and the high turnover of program managers and service providers make it also difficult to assess the long-term results of these investments.

When considering the data presented in Part II, the overall conclusion is that the regional and country-level efforts yielded limited results in terms of improvement of the health status of adolescents and youth, which in turn leads to the conclusion that changes must be made in the regional and country-level responses, to accelerate progress towards improvement of the health and wellness of young people in the Region.

The lessons learned in the past years already point to some of the changes needed. These include: ensuring that adolescent and youth health programs are multisectoral and address the social determinants of health; ensuring that approaches are evidence-based, target the groups in situations of vulnerability from an equity perspective, and are taken to scale; implementing rigorous M&E to inform strategic planning and timely adaptations to improve efficiency and effectiveness of programs and services; and developing new modalities for capacity building that will yield sustainable results.