Part II

The Current Status of the Health of Adolescents and Youth in the Americas

II.1 Introduction

The Regional Strategy for Improving Adolescent and Youth Health and the Plan of Action on Adolescent and Youth Health have the overarching goal of contributing to the health of young people in the Region of the Americas (4). This is to be accomplished by developing and strengthening an integrated health sector response and by implementing effective adolescent and youth health promotion, prevention, and care programs. The Plan of Action proposes a set of 8 health goals, with 19 targets, that are related to mortality, unintended injuries, violence, substance use and mental health, sexual and reproductive health, nutrition and physical activity, chronic diseases, and protective factors (4) (Annex II.A). The following sections of Part II of this report present a status update on the health of adolescents and youth in the Americas, based on these health goals.

II.2 Mortality and morbidity

Adolescence is generally a healthy stage of life, with low mortality and morbidity, compared with other age groups. The 2016 report from the Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing (3) proposed classifying countries into three categories, depending on the pattern of disease burden in the adolescent and youth population (10-24 years).

Box II.1: Regional adolescent and youth health goals 1-3

Goal 1: Reduce adolescent and youth mortality

- Reduce the mortality rate of adolescents and youth ages 10-24 years

Goal 2: Reduce unintentional injuries

- Reduce the mortality rate caused by road traffic injuries among men 15-24 years of age

Goal 3: Reduce violence

- Reduce the suicide rate among those 10-24 years old

- Reduce the homicide rate among men aged 15-24 years

Source: (4).

The first category is “multiburden countries,” with disability-adjusted life year (DALY2) rates due to infectious diseases, nutritional deficiency, and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) (including HIV) of 2,500 per 100,000 or more per year. These are countries with little evidence of having passed through an epidemiological transition. These nations tend to have high burdens of infectious and vaccine-preventable diseases, undernutrition, and adverse sexual and reproductive health events.

2 The sum of the years of life lost due to premature mortality and the years lost due to disability.

The second category is “injury-excess countries,” where the burden of disease shows evidence of having passed through the first phase of the epidemiological transition, but where rates of preventable injury are high. These are countries with DALY rates due to unintentional injuries and violence of 2,500 per 100,000 per year or more, combined with nutritional deficiency and SRH (including HIV) of less than 2,500 per 100,000.

The third category is “noncommunicable-disease-predominant countries.” These NCD-predominant nations have DALY rates of less than 2,500 per 100,000 for infectious diseases, nutritional deficiencies, and SRH/HIV, as well as for unintentional injuries and violence.

The Lancet report places the countries of North America in the NCD-predominant category, as well as Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay. Most of the remaining South American, Central American, and Caribbean countries are placed in the injury-excess category. A few countries, including Guatemala and Haiti, are in the multiburden category (3).

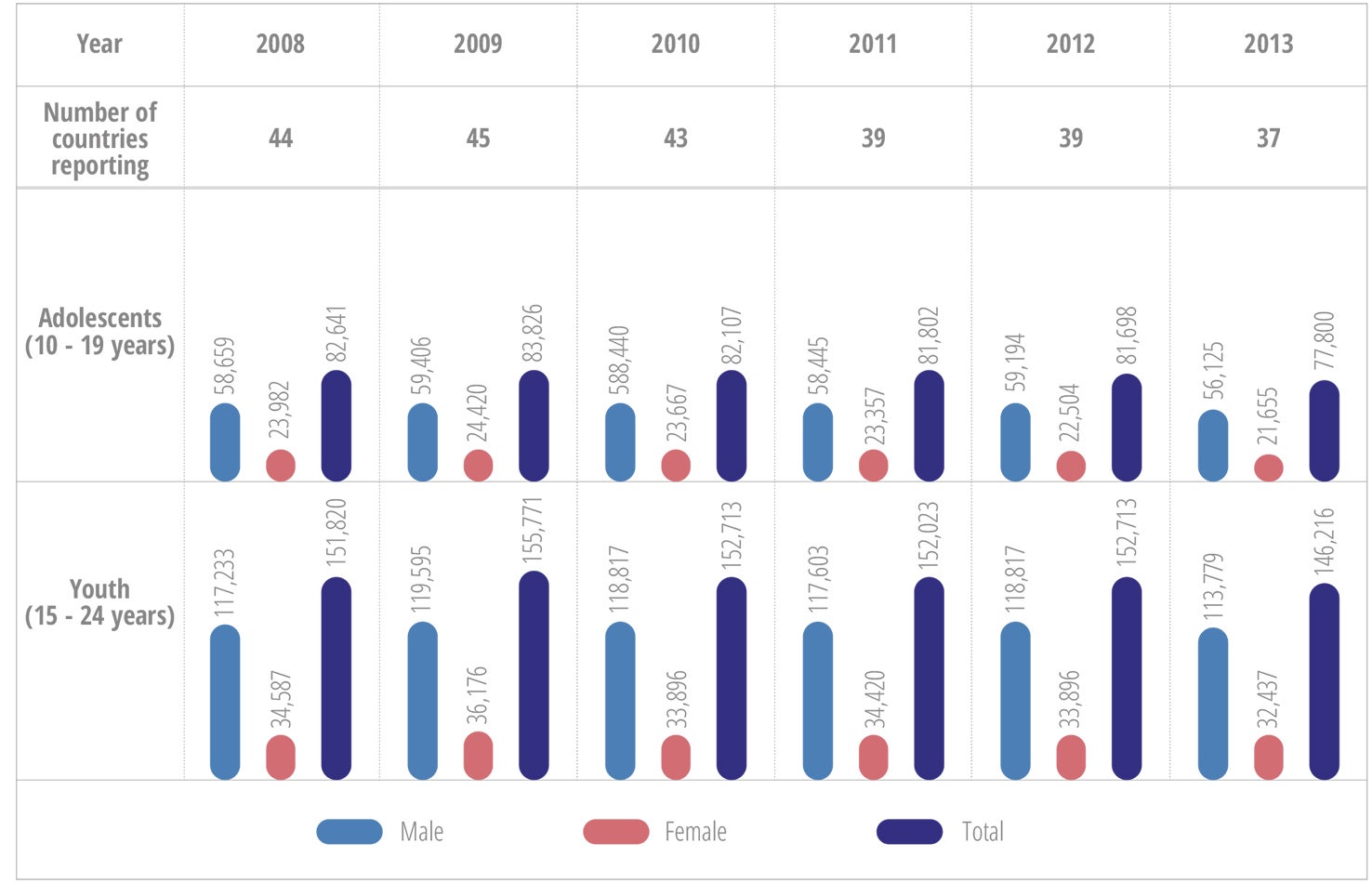

Each year in the Americas, around 80,000 adolescents (10-19 years) and 150,000 youth (15-24 years) die (Figure II.1). On average, 70% to 80% of these deaths are among males.

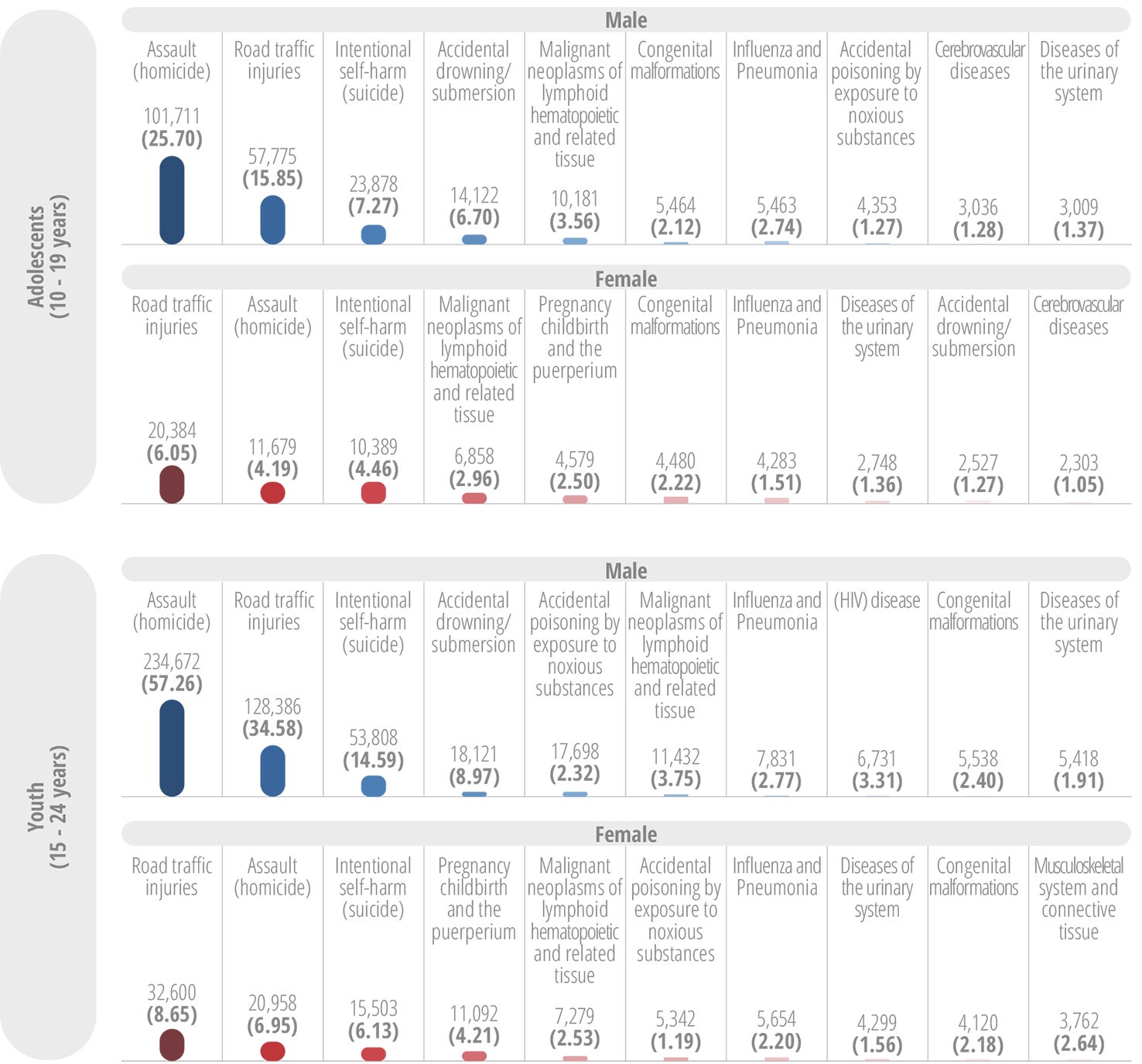

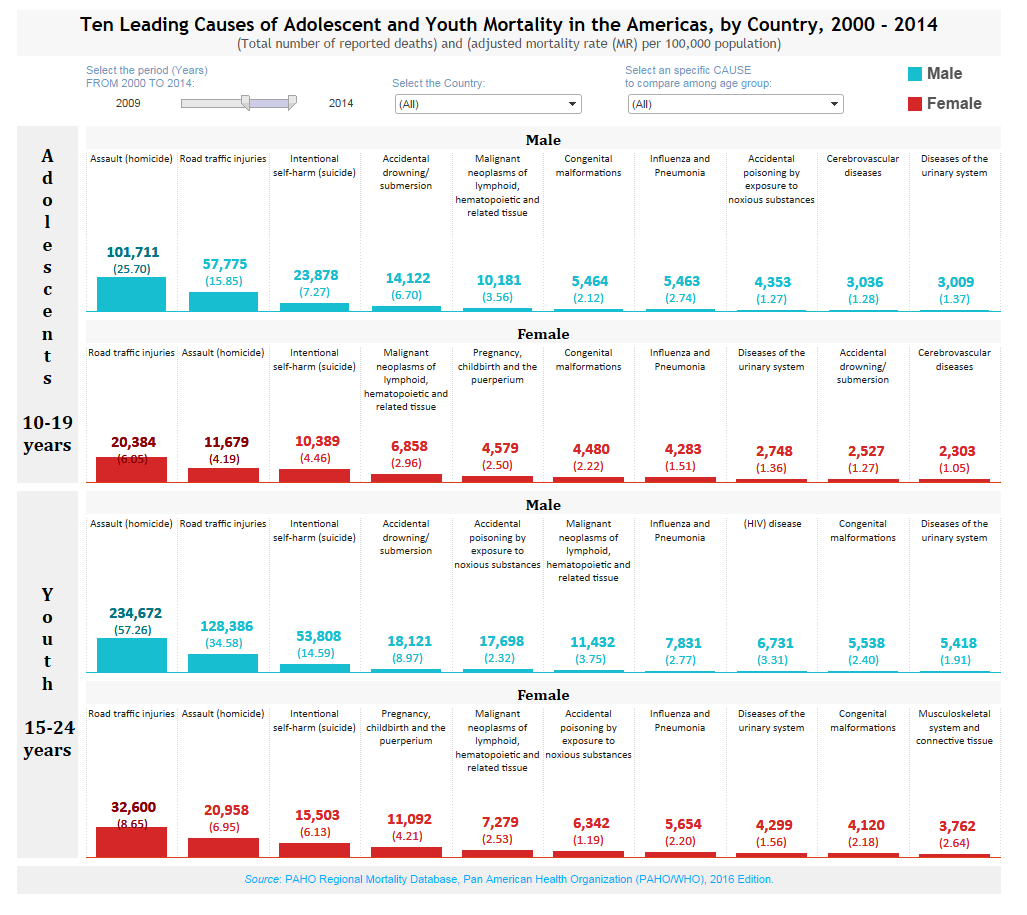

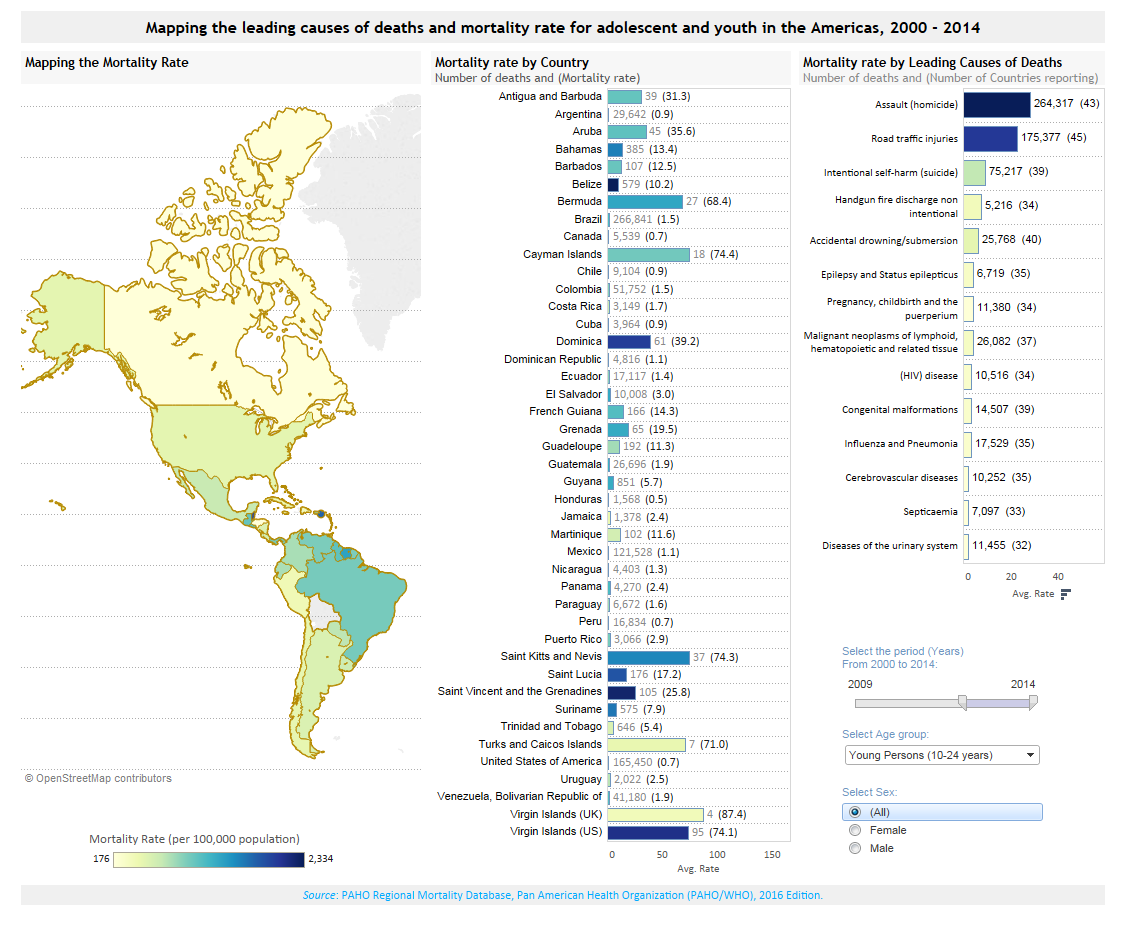

Homicide, suicide, and road traffic injuries are the leading causes of death among adolescents and youth in the Americas (Figure II.2, Annex II.B, Annex II.C).

Data Visualization

Ten Leading Causes of Adolescent and Youth Mortality in the Americas, by Country, 2000-2014

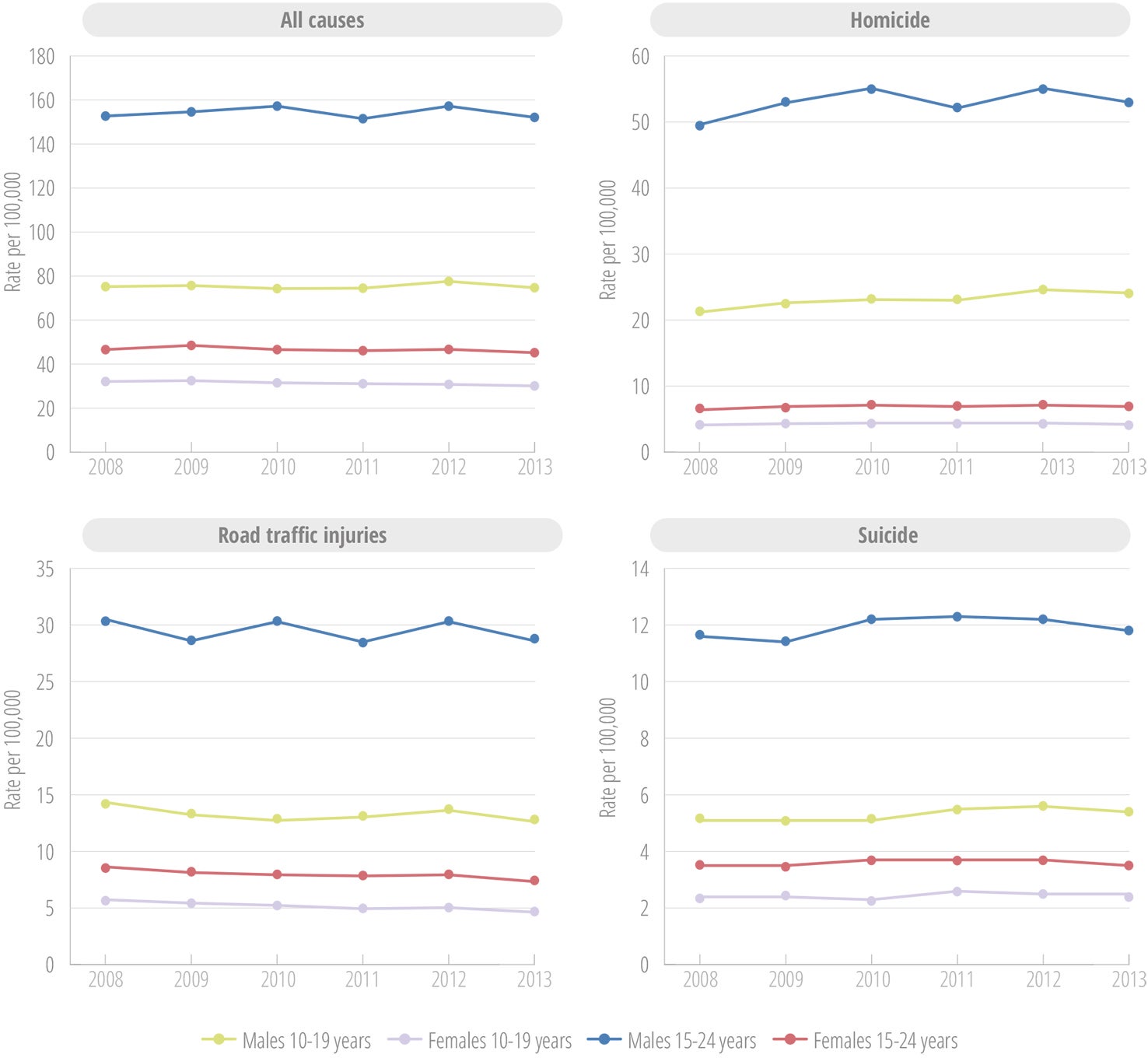

The data show little variation in adolescent and youth mortality over the 2008-2013 period (Figure II.3). Consistently, males die at higher rates, with the highest mortality rates in males aged 15-24 years.

Data Visualization

Mapping the leading causes of deaths and mortality rate for adolescent and youth in the Americas, 2000-2014

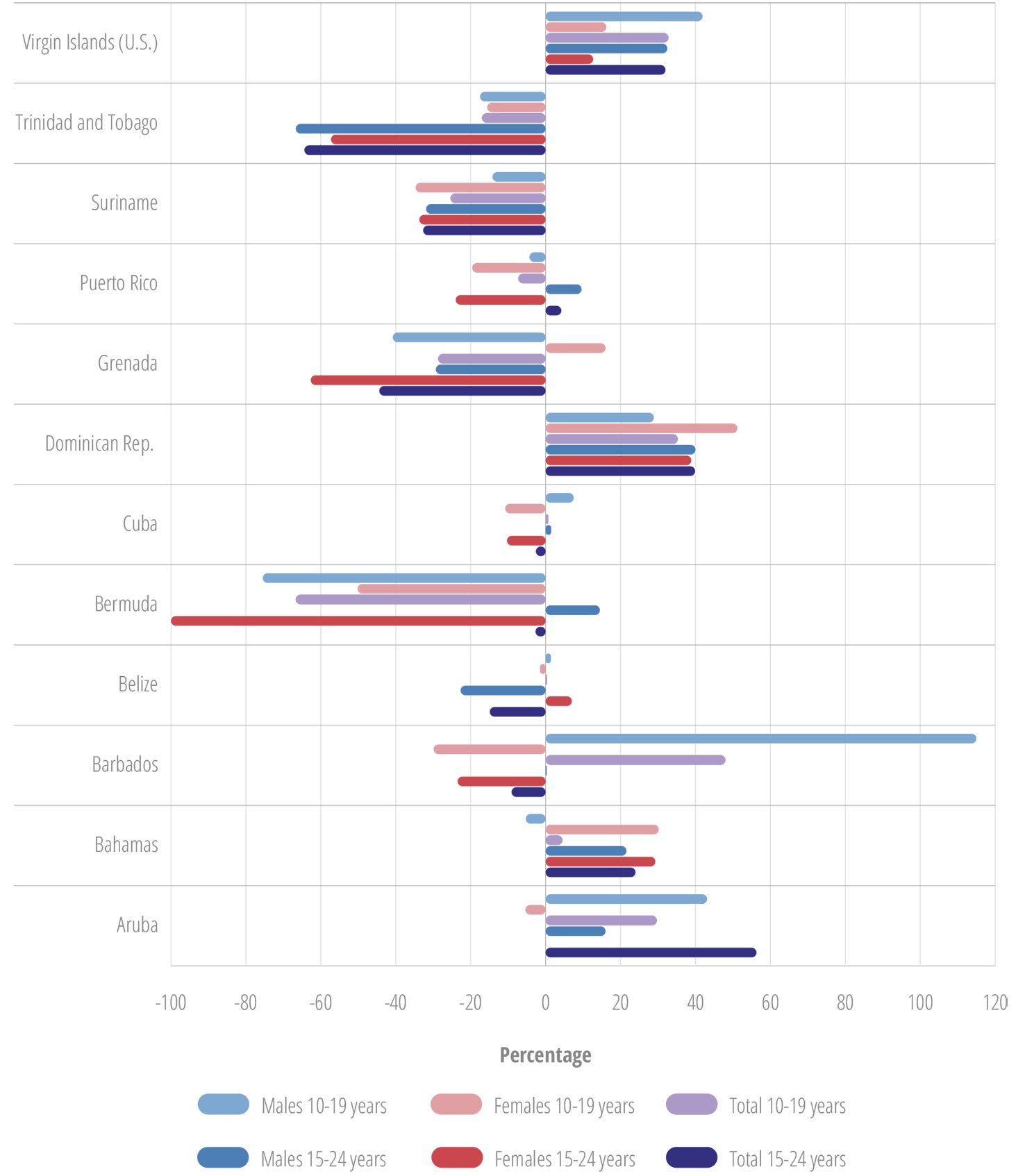

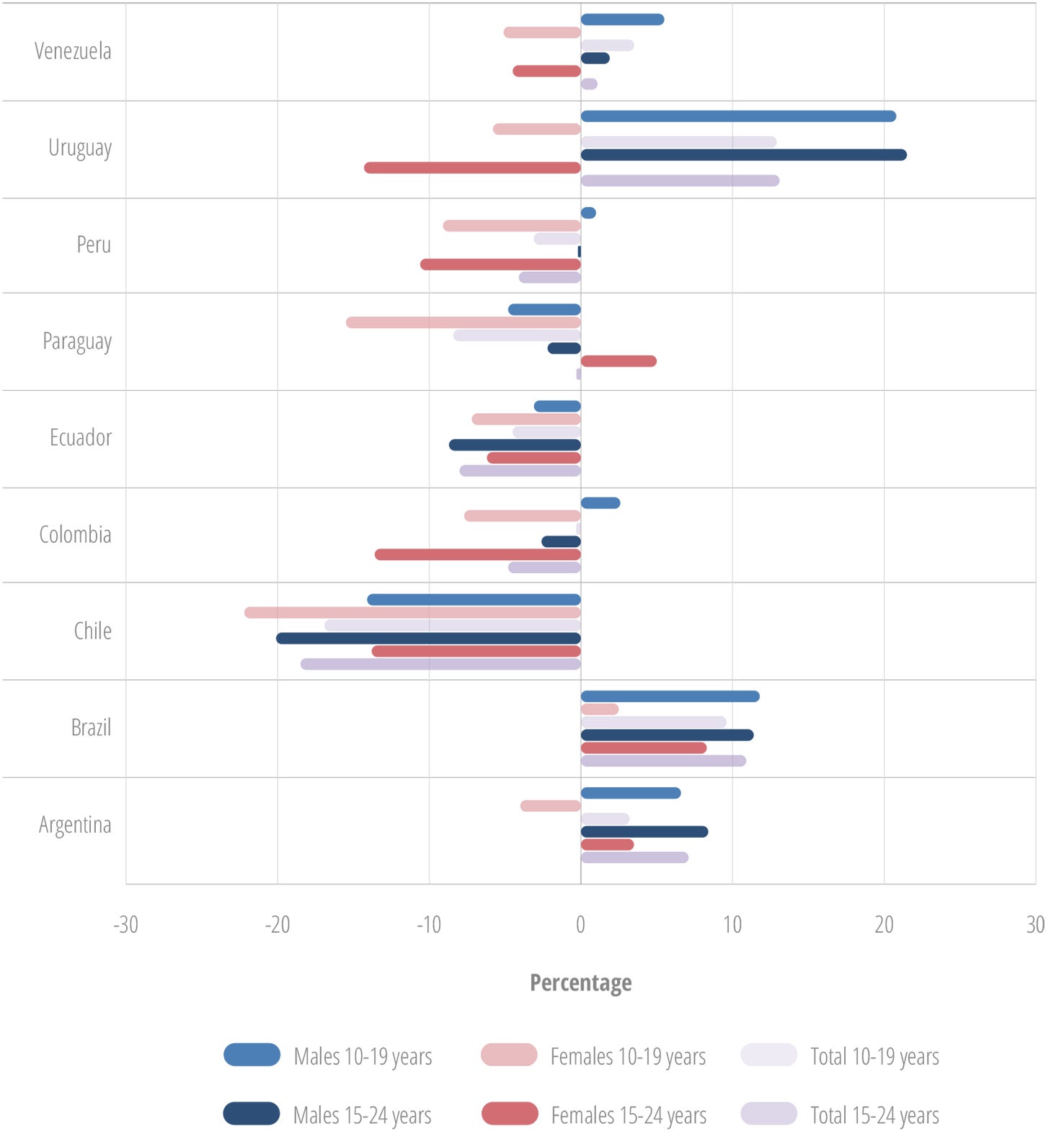

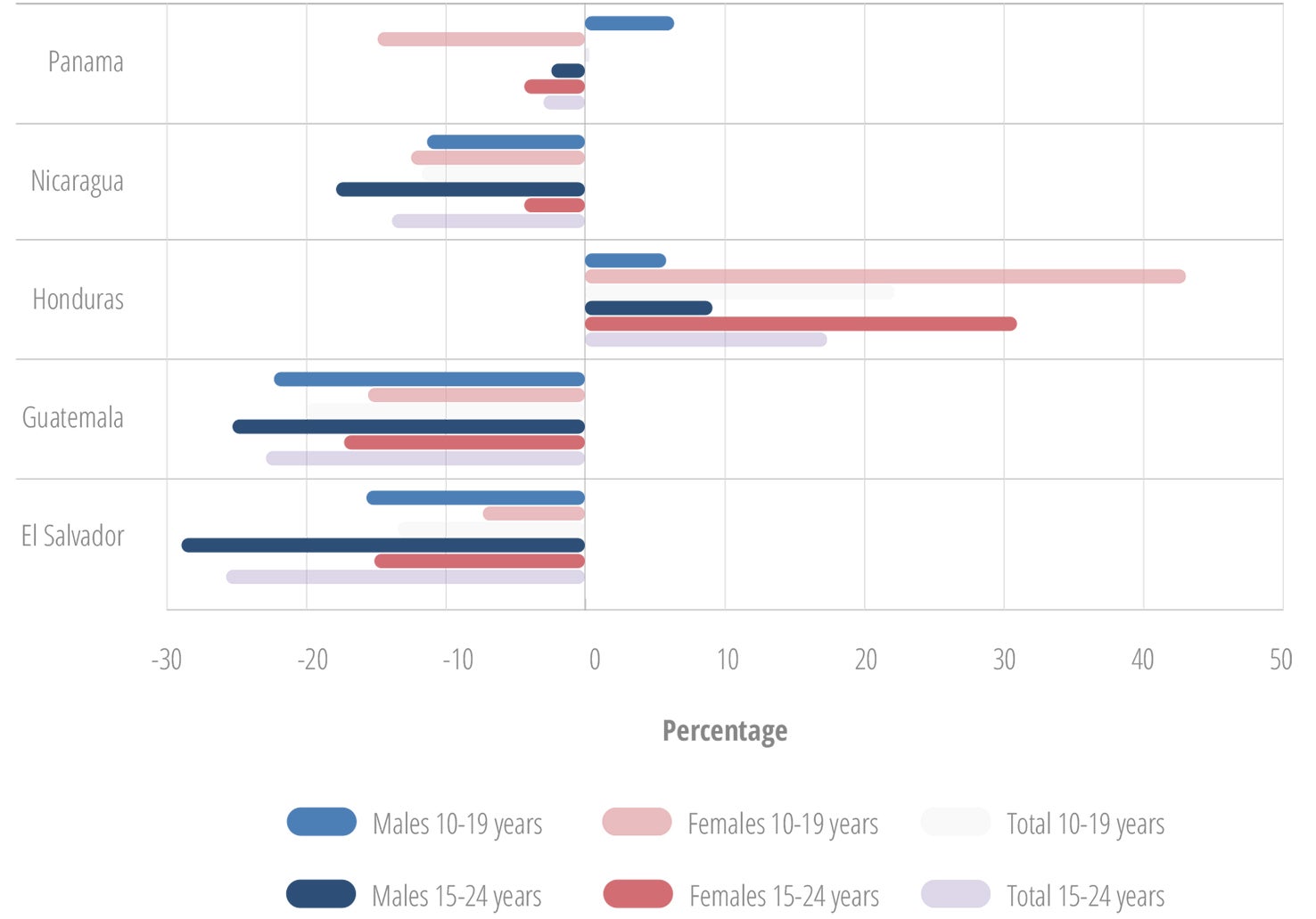

Analysis of percentage changes in mortality for the 2008-2012 period shows differences among countries, between age groups, and between the two sexes that can contrast with regional averages. While some countries show progress in some or all groups, others are dealing with increased mortality (Figure II.4 through Figure II.6). (It is important to note that due to the small population sizes in some Caribbean countries, relatively small changes in the number of deaths can create major shifts in the trends.)

The countries with the largest percentage decreases in overall mortality rate included Bermuda, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, and Suriname. The countries with the largest percentage increases in overall mortality rate included Aruba, the Bahamas, and the Dominican Republic. Notably, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Mexico had increases in total mortality rate for both males and females in all age groups.

Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua had decreased mortality rates in both males and females of all age groups. The remaining countries showed differences between the sexes and age groups.

The countries with the largest percentage decreases in all homicides included Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Saint Kitts and Nevis. For suicide, they were Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and Suriname. And for mortality due to road traffic injuries, they were Belize, Bermuda, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Peru, Puerto Rico, Suriname, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The countries with the largest increases in homicide rates among males were Belize, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru. Of particular concern was the significant increase in homicide rates among females in a number of countries, including the Bahamas, Belize, Cuba, Mexico, Paraguay, and Peru. Also worrisome was suicide, in both sexes, with the largest increases being in Argentina, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Peru, and Puerto Rico. Similarly concerning are the mortality rates due to road traffic injuries, with the largest increases in Argentina, Aruba, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Uruguay.

Intentional homicide is by far the most important cause of death among young people, in particular males, in the Region. The grand majority of homicides are also perpetrated by males (74). In order to improve efforts aimed at reduction of homicide, it is critical to understand the details and patterns of these events (who, how, and why). Intentional homicides can be related to other criminal activities (robberies, gangs, organized crime), to interpersonal conflict, or to socio-political causes (74). These relationships can vary significantly between countries. For example, for the period 2008-2011, 44% of homicides in Jamaica were related to gangs and organized crime, and 40% were related to robbery or other criminal acts. By contrast, 47% of homicides in Costa Rica during the period 2006-2012 were related to robbery or other related criminal acts, and 36% were related to interpersonal conflicts (74).

In terms of mechanisms, homicides can be perpetrated with firearms, sharp objects (such as knives), or other means (i.e., strangulation, blunt force). In the Americas, between 60% and 70% of intentional homicides are perpetrated with firearms. At the country level, this can vary: for example in 2011, 24% of homicides (all ages) in Costa Rica were perpetrated with firearms, 38% with sharp objects, 12% with blunt force, and the remaining 26% through other means. On the other hand, 67% of homicides in Belize in the same year were perpetrated with firearms, and 20% with blunt force (74).

Beyond homicide deaths, several forms of nonfatal violence also contribute to the burden of disease among young persons in the Region. These include physical, emotional, and mental harm caused by bullying, physical, sexual, and psychological abuse.

It is important to note that adolescent and youth deaths do not happen randomly, but are often related to contextual factors, including the social determinants of health, such as education and socioeconomic status. The following paragraphs and figures describing selected countries illustrate the importance of advanced analysis of mortality data, for increased understanding of the relationship between adolescent and youth mortality and social determinants, and the most vulnerable groups within countries and communities.

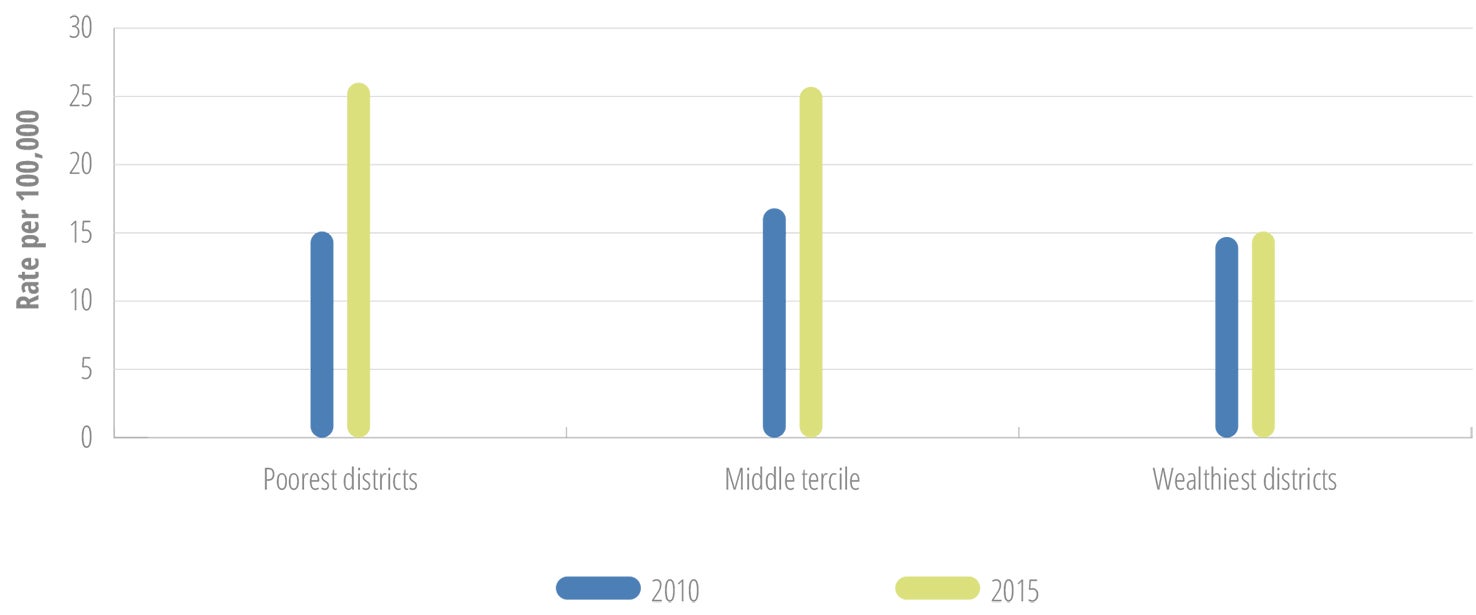

For example, an analysis of deaths in youth aged 15-24 years due to road traffic injuries in Belize showed that between 2010 and 2015, the rate remained stable in the districts with the highest wealth index, while it increased significantly in the poorer districts (Figure II.7) (75).

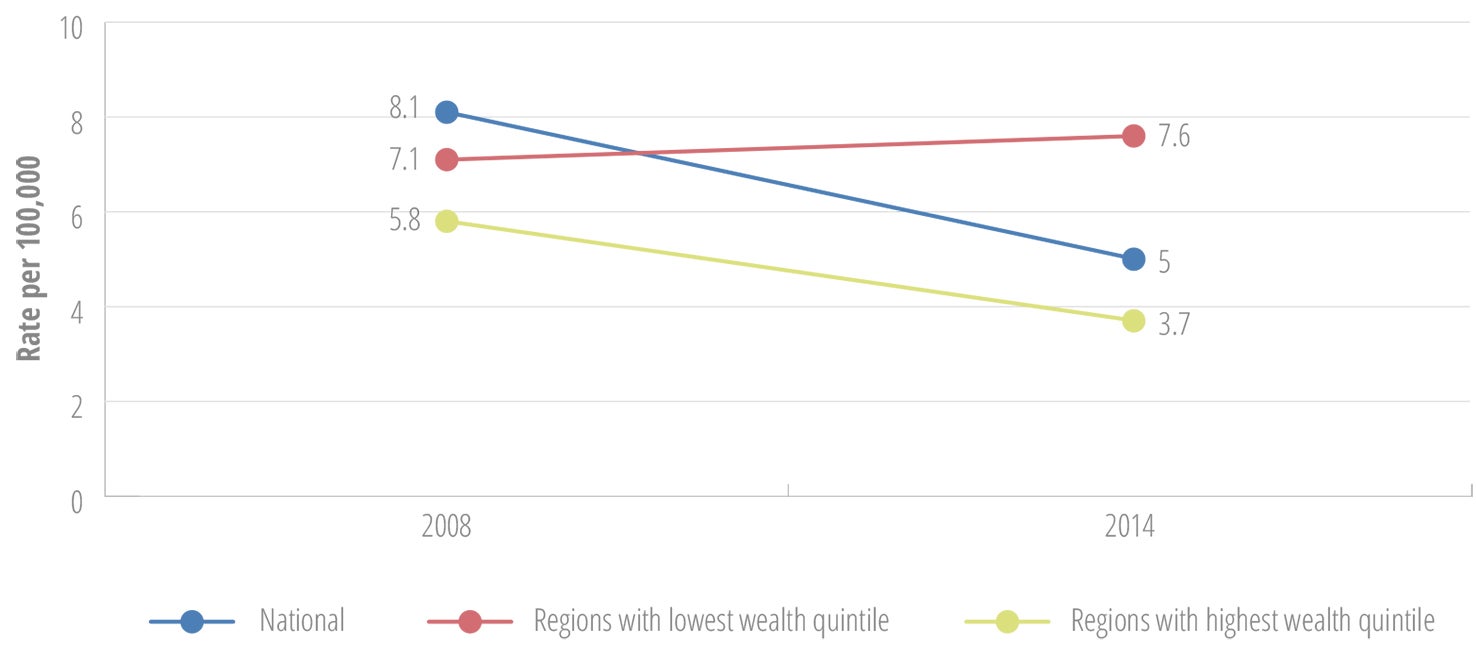

National averages may disguise inequalities in subgroups. In 2014, Chile reported an adolescent suicide rate of 5.1 per 100,000 (39). However, analysis of suicides by region indicated marked differences in patterns among the regions in the country. Between 2008 and 2014, the regions with the highest income had a downward trend in suicide rates, while the rates in the poorer regions increased (Figure II.8) (75).

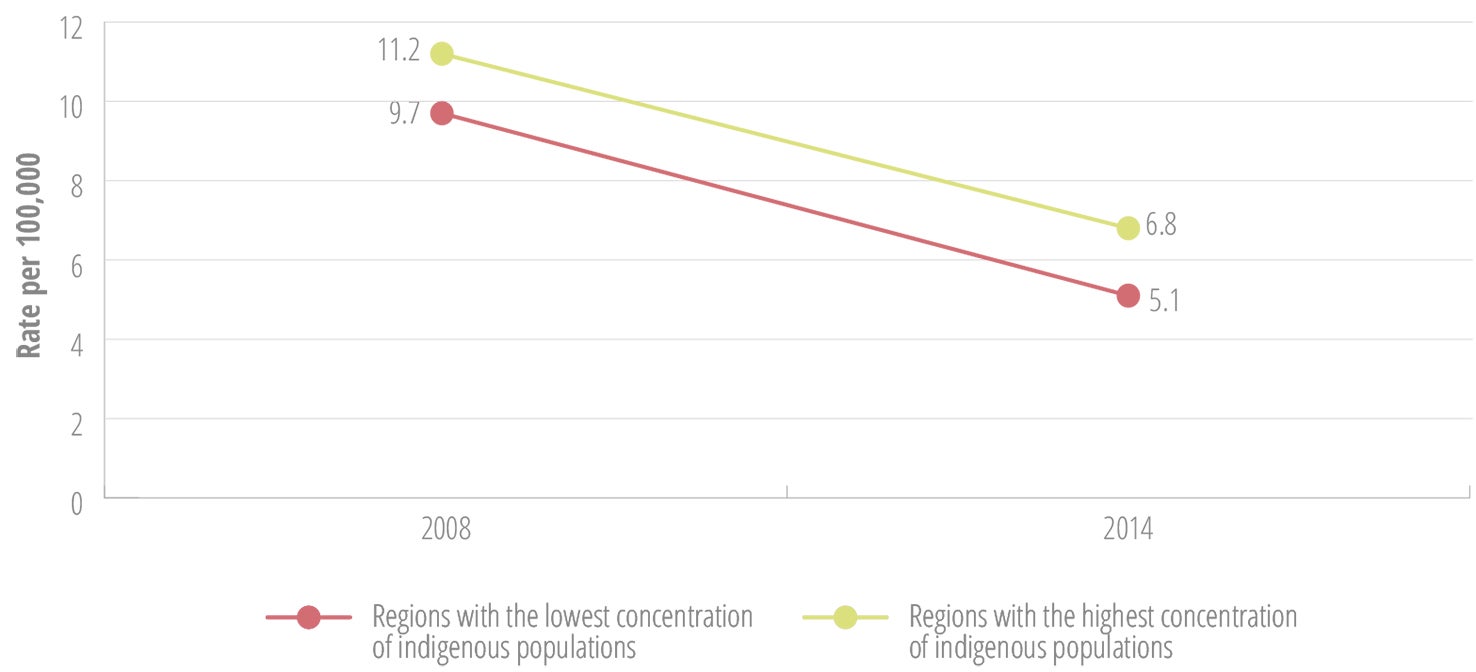

When analyzed by the concentration of indigenous populations in the regions in Chile, the data showed consistently higher adolescent suicide rates in the regions with the highest concentrations of indigenous populations, as compared with the regions with the lowest concentrations, and also the national rates (Figure II.9).

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for a disease or health condition are calculated as the sum of the years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality in the population and the years lost due to disability (YLD) for people living with the health condition or its consequences. One DALY can be thought of as one lost year of “healthy” life. The sum of these DALYs can be thought of as a measurement of the gap between current health status and an ideal health situation, free of disease and disability (76).

According to findings from an analysis of data from the 2015 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study conducted for PAHO by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the leading causes of DALYs in adolescents aged 10-14 years are iron deficiency anemia and skin diseases, such as acne, interpersonal violence and road traffic injuries in the age groups 15-19 years and 20-24 years (Table II.1).

| Rank | 10-14 years | 15-19 years | 20-24 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Both sexes | Male | Female | Both sexes | Male | Female | Both sexes | |

| 1 | Iron deficiency anemia (1,354) | Iron deficiency anemia (1,046) | Iron deficiency anemia (1,203) | Interpersonal violence (3,626) | Skin diseases (967) | Interpersonal violence (2,055) | Interpersonal violence (5,685) | Depressive disorders (1,363) | Interpersonal violence (3,123) |

| 2 | Skin diseases (772) | Skin diseases (922) | Skin diseases (846) | Road traffic injuries (1,724) | Depressive disorders (965) | Road traffic injuries (1,114) | Road traffic injuries (2,748) | Anxiety disorders (910) | Road traffic injuries (1,646) |

| 3 | Asthma (661) | Asthma (603) | Asthma (633) | Skin diseases (830) | Anxiety disorders (792) | Skin diseases (897) | Self-harm (1,001) | Migraine (768) | Depressive disorders (1,130) |

| 4 | Road traffic injuries (571) | Anxiety disorders (568) | Conduct disorders (471) | Depression (645) | Migraine (713) | Depressive disorders (802) | Depressive disorders (902) | Skin diseases (740) | Low back and neck pain (709) |

| 5 | Conduct disorders (562) | Migraine (567) | Road traffic injuries (443) | Self-harm (628) | Low back and neck pain (575) | Anxiety disorders (597) | Low back and neck pain (691) | Low back and neck pain (729) | Skin diseases (683) |

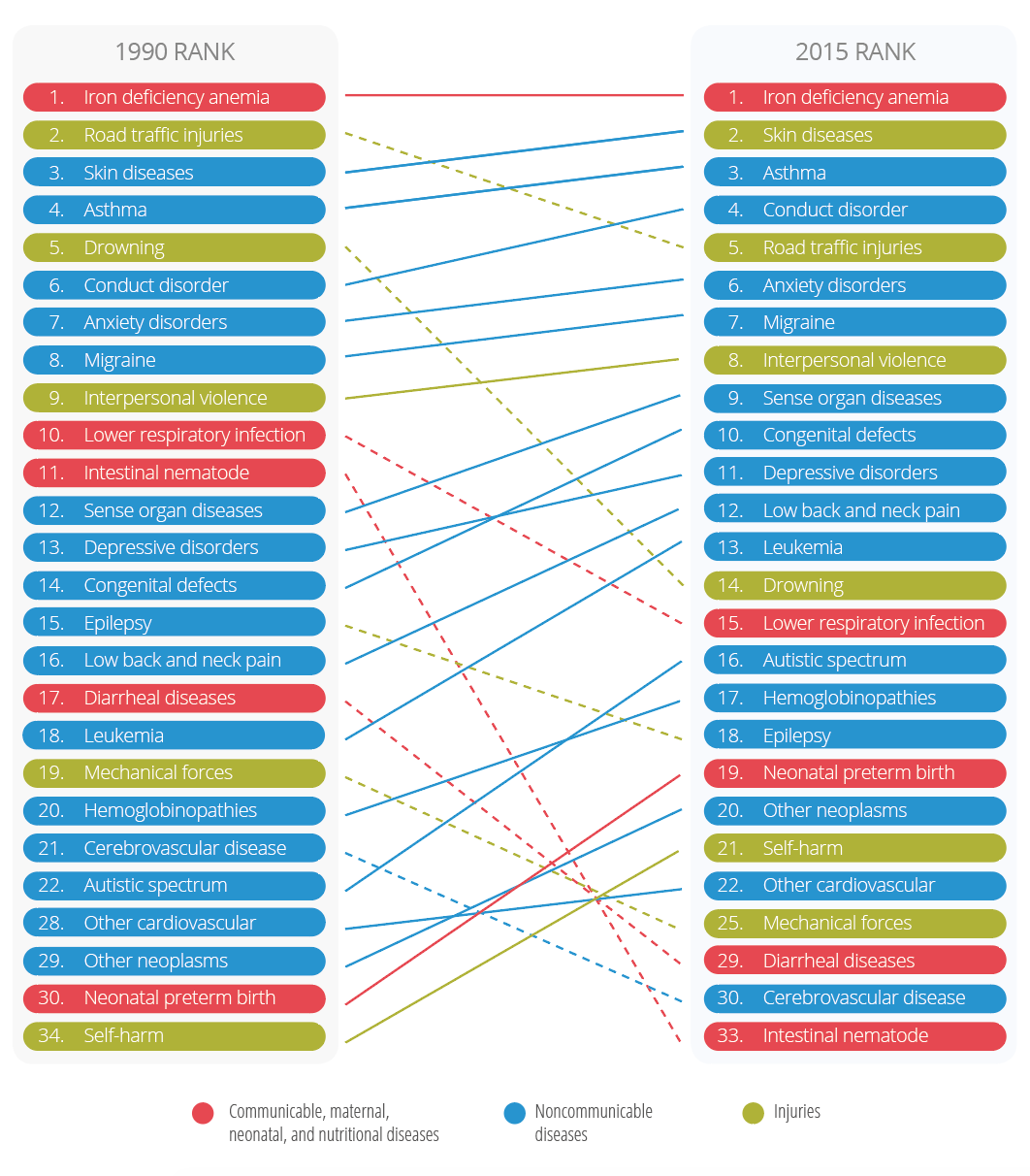

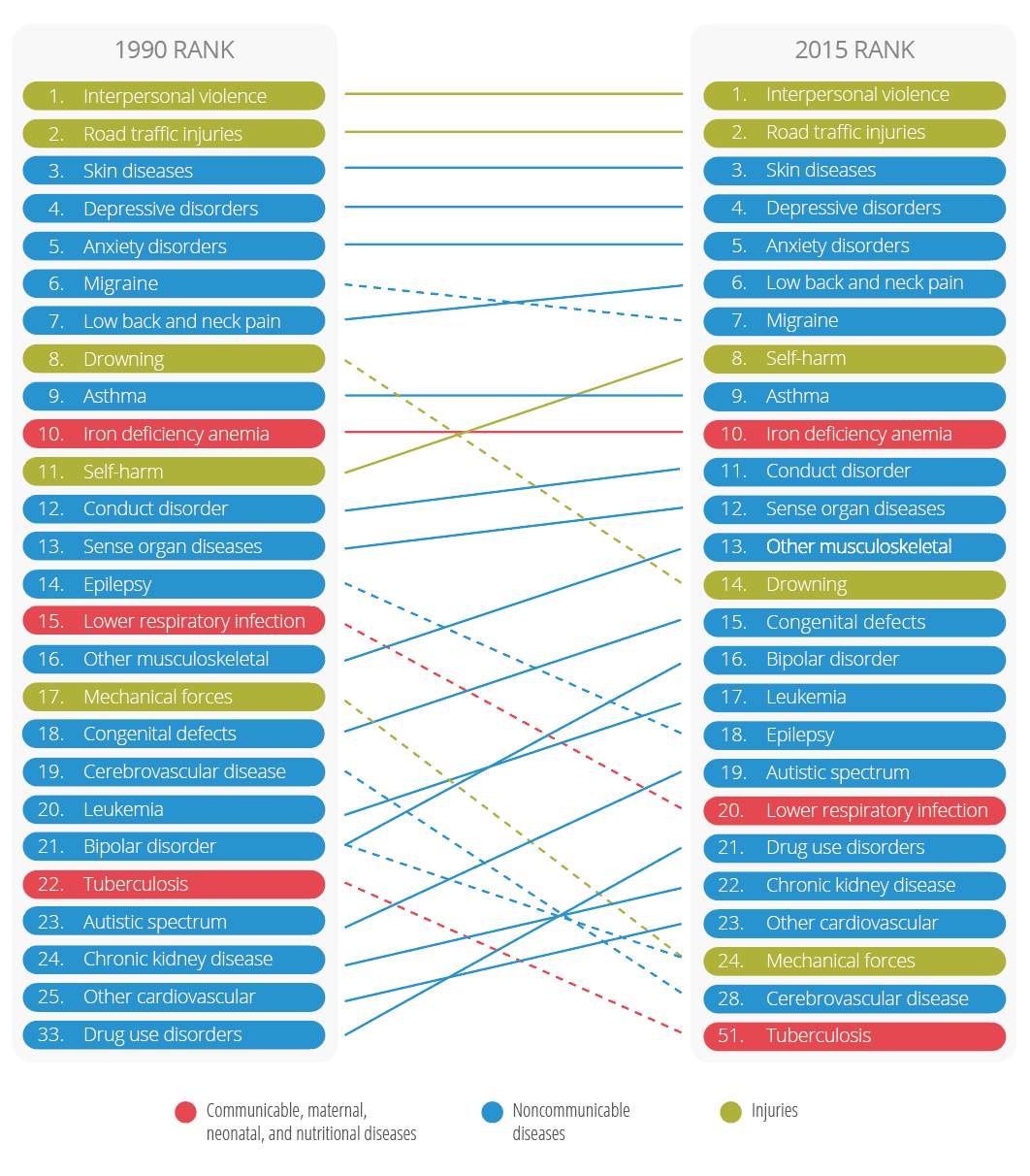

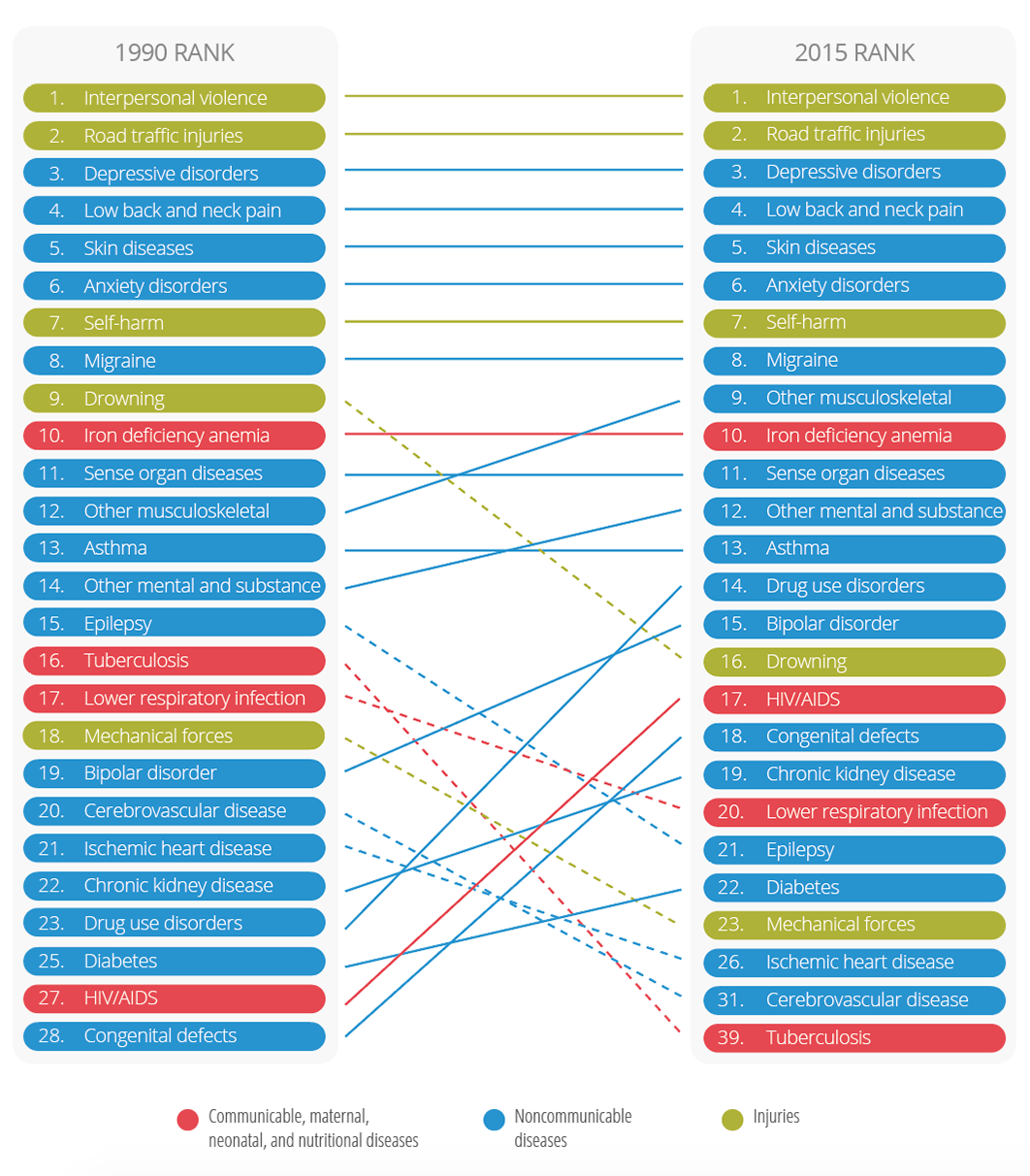

According to the GBD analysis, the leading causes of DALYs of young persons in Latin America and the Caribbean have shifted since 1990, with communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases generally declining in rank, and conditions such as self-harm (suicide and attempted suicide) and conduct and mental health disorders becoming more prominent (Figure II.10, Figure II.11, and Figure II.12).

In the age group 10-14 years, intestinal nematode infections, lower respiratory infections, drownings, and diarrheal diseases dropped substantially on the list of DALYs between 1990 and 2015, and road traffic injuries, conduct disorders, and asthma went up in rank. Iron deficiency anemia remained the top cause of DALYs in the age group 10-14 years, in both 1990 and 2015 (Figure II.10).

In the older adolescents (15-19 years), the five leading causes for DALYs lost remained constant, with violence, injuries, and mental health disorders as prominent causes. Self-harm rose in rank from 11th to 8th, and drownings went down, from 8th to 14th (Figure II.11).

Similarly, the top eight leading causes in youth 20-24 years old remained stable. Drug use disorders, HIV/AIDS, and congenital defects rose noticeably in rank, and drownings, epilepsy, and tuberculosis declined substantially (Figure II.12).

In Latin America and the Caribbean in 2015, the leading risk factors for DALYs for young adolescents (10-14 years) were malnutrition, alcohol and drug use, poor kidney function, and unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing. Prominent risk factors for youth 15-24 years included alcohol and drug use, occupational risks, unsafe sex, sexual abuse and violence, and malnutrition (Table II.2). Tobacco featured as risk factor number 11 for youth (15-24 years).

| Rank | 10–14 years | 15–19 years | 20–24 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 1 | Malnutrition | Malnutrition | Alcohol and drug use | Malnutrition | Alcohol and drug use | Occupational risk |

| 2 | Alcohol and drug use | Low glomerular filtration | Occupational risk | Occupational risk | Occupational risk | Malnutrition |

| 3 | Unsafe water, sanitation and handwashing | Unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing | Malnutrition | Alcohol and drug use | Unsafe sex | Alcohol and drug use |

| 4 | Low glomerular filtration | Unsafe sex | Low glomerular filtration | Sexual abuse and violence | High fasting plasma glucose | Sexual abuse and violence |

| 5 | Unsafe sex | High fasting plasma glucose | High fasting plasma glucose | High fasting plasma glucose | Low glomerular filtration | Unsafe sex |

| 6 | High fasting plasma glucose | Alcohol and drug use | Unsafe sex | Low glomerular filtration | Malnutrition | High fasting plasma glucose |

| 7 | Air pollution | Sexual abuse and violence | Unsafe water, sanitation and handwashing | Unsafe sex | High blood pressure | Low glomerular filtration |

| 8 | High blood pressure | Air pollution | High blood pressure | Unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing | Sexual abuse and violence | High blood pressure |

| 9 | Tobacco | High blood pressure | Sexual abuse and violence | High blood pressure | Unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing | Unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing |

| 10 | Other environmental | Tobacco | Air pollution | Air pollution | Air pollution | Air pollution |

The presented data on adolescent and youth mortality and DALYs lost underline the lack of progress and the unfinished regional agenda for adolescent and youth mortality and risk factors. For the Region, among the critical requirements for progress in reducing preventable adolescent and youth mortality are increasing the understanding of the specific circumstances of these deaths, identification of the most affected groups, and application of evidence-based interventions to address the circumstances and risk factors.

Beyond homicide, other types of violence are highly relevant when it comes to adolescents and youth. These include nonfatal violence, bullying, and sexual violence, which all contribute to disabilities, depression, and such high-risk behaviors as smoking, substance use, and sexual risk-taking.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and PAHO recommend evidence-based interventions for the prevention of adolescent suicide, road traffic injuries, and youth violence (including bullying), applying an ecological perspective (Annex II.D1) (6, 76).

II.3Adolescent and youth mental health and substance use

Mental health

The WHO defines mental health as a “state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (78). WHO’s Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 (78) uses the term “mental disorders” to denote a range of mental and behavioral disorders that fall within the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). These include depression, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, dementia, substance-use disorders, intellectual disabilities, and developmental and behavioral disorders. The Action Plan also covers suicide prevention and such conditions as epilepsy (78). Mental disorders have been associated with increased alcohol use; violence; such diseases as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and HIV; increased risk of poverty; and premature death (78).

Box II.2: Regional adolescent and youth health goal 4

Reduce substance use and promote mental health

- Reduce the percentage of adolescents between the ages of 13 and 15 who have consumed one or more alcoholic beverages during the last 30 days

- Reduce past-month use of illicit substances among those 13-15 years old

- Reduce tobacco use among adolescents and youth 15-24 years of age

Source: (4).

The WHO Action Plan has four objectives: 1) to strengthen effective leadership and governance for mental health; 2) to provide comprehensive, integrated, responsive mental health and social care services in community-based settings; 3) to implement strategies for promotion and prevention in mental health; and 4) to strengthen information systems, evidence, and research for mental health. The Action Plan identifies the early stages of life as an important opportunity to promote mental health and prevent mental disorders, as up to 50% of mental disorders in adults begin before the age of 14 years (78).

After the WHO Action Plan was approved, the PAHO Member States adopted the Plan of Action on Mental Health 2015-2020 in 2014 (77). The goal of the regional Plan of Action is to promote mental well-being; prevent mental and substance-related disorders; offer care; enhance rehabilitation; emphasize recovery; and promote the human rights of persons with mental and substance-related disorders, in order to reduce morbidity, disability, and mortality (77).

In addition to suicide deaths, suicidal behaviors (including ideation, planning, and attempts) are important indicators of the mental health of young people. An analysis of data generated by the most current Global School-based Health Surveys (GSHS) conducted in 28 LAC countries between 2007 and 2013 provides some insight into suicidal behaviors for subregions of the Americas (Annex II.E) (79). The percentage of students aged 13-15 years who seriously considered suicide (ideation) ranged from 14.8% in Central America to 20.7% in the English-speaking Caribbean, and the percentage of students who actually attempted suicide ranged from 13.2% in Central America to 18.0% in the Caribbean. The use of alcohol and the perception of having poor social support substantially increased the prevalence of suicidal behaviors in both males and females in this age group. By contrast, having strong parental relationships appeared to serve as a protective factor against suicidal behaviors in both sexes.

These GSHS results are consistent with the findings of a multicountry analysis of a school health survey conducted in six Overseas Caribbean Territories (OCTs) (Aruba, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat, Saint Eustatius, and Saint Maarten) during 2011-2013 (80). In this study, 23.6% of the respondents ages 15-19 years had seriously considered suicide in the 12 months preceding the study. Statistically significant associations were found between suicidal behaviors and family connectedness. Respondents with very low to low family connectedness were more likely to consider or attempt suicide (80).

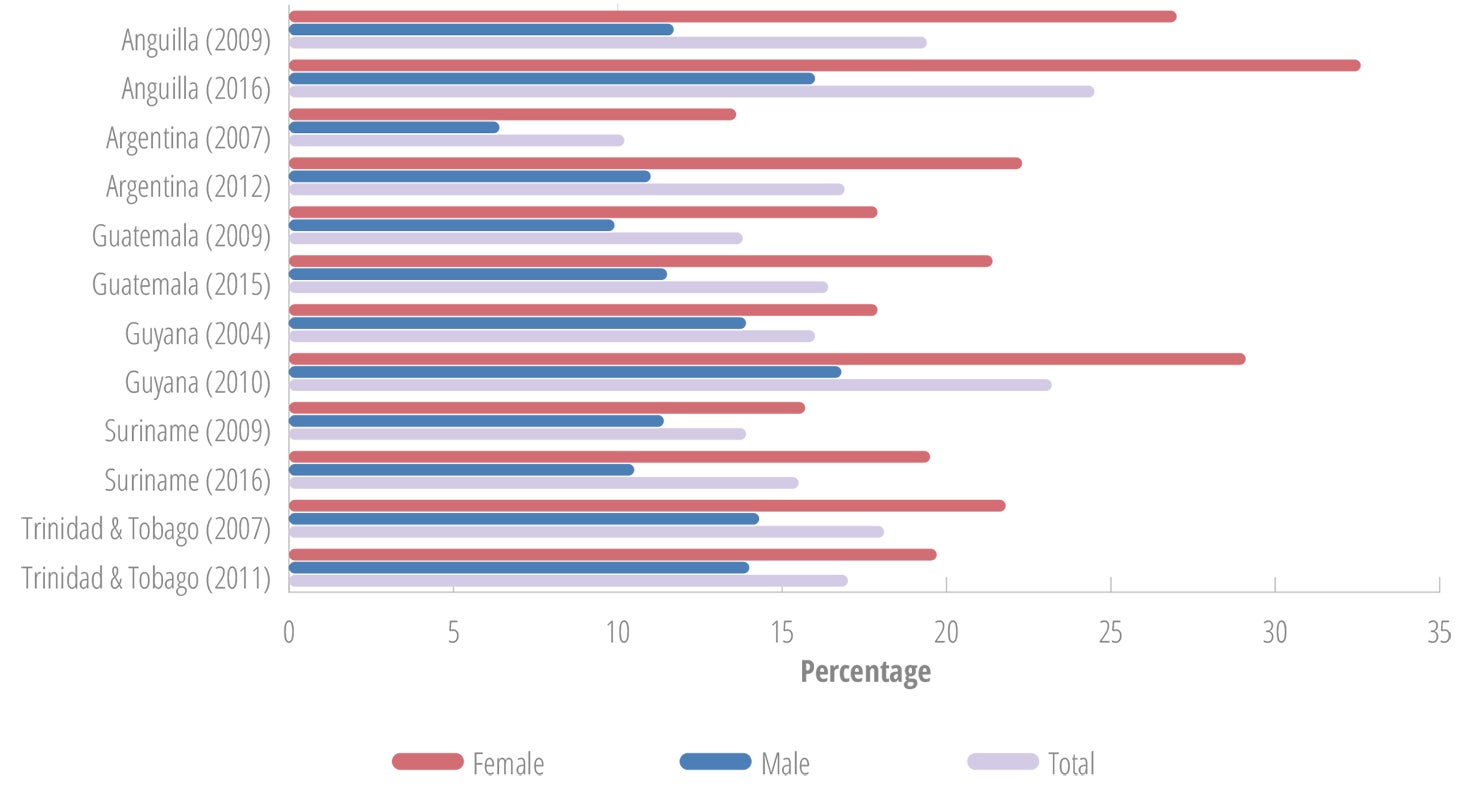

In the countries with two GSHS data points for suicidal ideation, the percentage of adolescents who seriously considered suicide was similar to or higher than the previous survey results (Figure II.13), suggesting that the situation is worsening instead of improving (79).

Substance use

The use of substances by adolescents is not just a public health concern because of the contribution to DALYs lost due to mortality and disability, and the negative behavioral consequences associated with intoxication. There is a growing body of evidence from neuroscience indicating that the use of psychoactive substances during adolescence, particularly heavy use, may have implications across the life course due to the effect on brain development (12, 13).

Psychoactive substances may generate neural adaptations that increase the risk for substance-use disorders in adulthood. In addition, adolescent alcohol and marijuana users have shown changes in brain structure and functions, including lower brain volume in several regions of the brain, and reduced white matter integrity. Studies have associated reduced white matter integrity with cognitive instability, and higher white matter integrity with optimal cognitive, behavioral, and emotional development (12, 13).

Alcohol and other substance use in youth has been associated with increased risk of motor vehicle crashes, as well as violence, reduced school performance, sexual risk behaviors, and relationship challenges with parents and peers (12, 13, 82-85). The following subsections will review the use of alcohol, tobacco, and psychoactive substances in young persons in the Region of the Americas.

One of the main sources for standardized information on substance use among young people is the GSHS, which is coordinated by the CDC and WHO and collects data among students aged 13-15 years (recently extended to 17 years) (81).

A second major source of information on substance use among young people is the Organization of American States (OAS). The Inter-American Observatory on Drugs (OID) is the statistical, information, and scientific research branch of the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD), which the OAS established in 1986. The OID helps countries to improve the collection and analysis of drug-related data by promoting the establishment of national observatories and the use of standardized methods. The OID publishes studies and comparative analyses regarding drug issues in the Americas, based on the work of national drug observatories. The Report on Drug Use in the Americas, 2011 (86), was the first analysis of drug trends in OAS Member States, covering the period of 2002-2009 and dealing with trends in five groups of substances. The Report on Drug Use in the Americas, 2015 (87), contains an exhaustive analysis of drug use in OAS Member States and offers a hemispheric and subregional outlook with respect to the consumption of psychoactive substances in recent years. The 2015 publication is based on information provided directly by Member States. The information was updated to the end of 2014, and came mainly from three sources: national studies among secondary school students, general population studies, and surveys of university students. The secondary school student surveys covered the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades (or the equivalent in each country), corresponding with the ages 13, 15, and 17.

The GSHS and OAS data are used in this report. However, their age groups and data collection methods are not identical and so should not be compared.

Alcohol

Dimensions of alcohol consumption that correlate with harms caused by alcohol include the patterns of drinking as well as the overall volume of drinking over the past month, the past year, or the lifetime. Any use of alcohol among adolescents is considered a risk, given the impact of alcohol on brain development. The earlier the initiation of alcohol use, the higher the risk of having episodes of heavy drinking and developing an alcohol use disorder later in life. Any episodic drinking occasion is a risk for intoxication, injuries, or even death. It is important to note that in non-tolerant youth, lower alcohol concentrations can lead to serious intoxication and poisoning. In the GSHS, the prevalence of heavy alcohol use is defined as at least five drinks (or the equivalent of 60 grams of pure alcohol) on a drinking occasion in the past 30 days (81), which is the same definition used in adult surveys, to allow for comparison between the age groups (86). The Inter-American Uniform Drug Use Data System (SIDUC) defines binge drinking as the consumption of five drinks or more on a single occasion during the two weeks prior to the survey, expressed as a percentage of the respondents who consumed alcohol in the past month (86, 87).

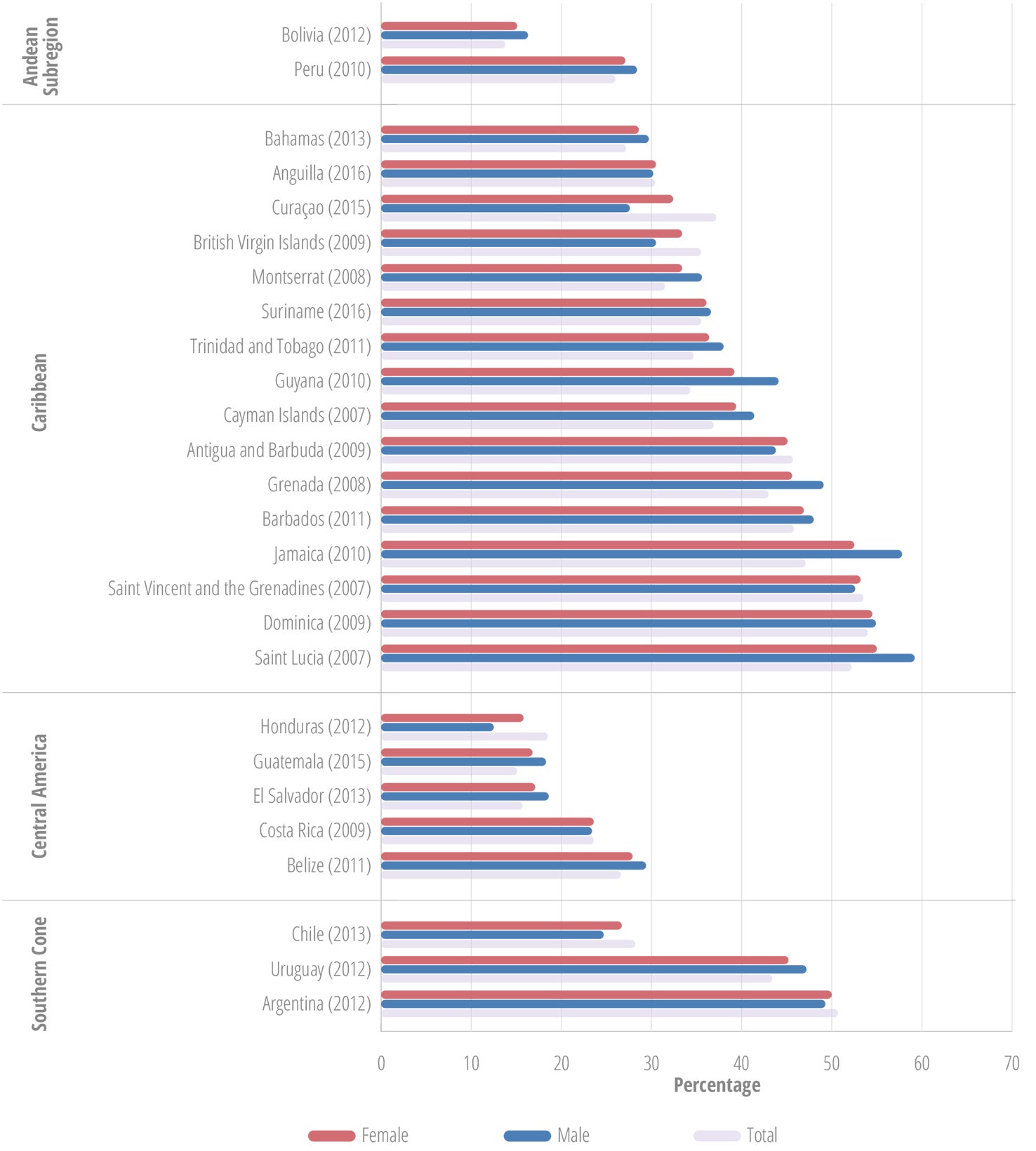

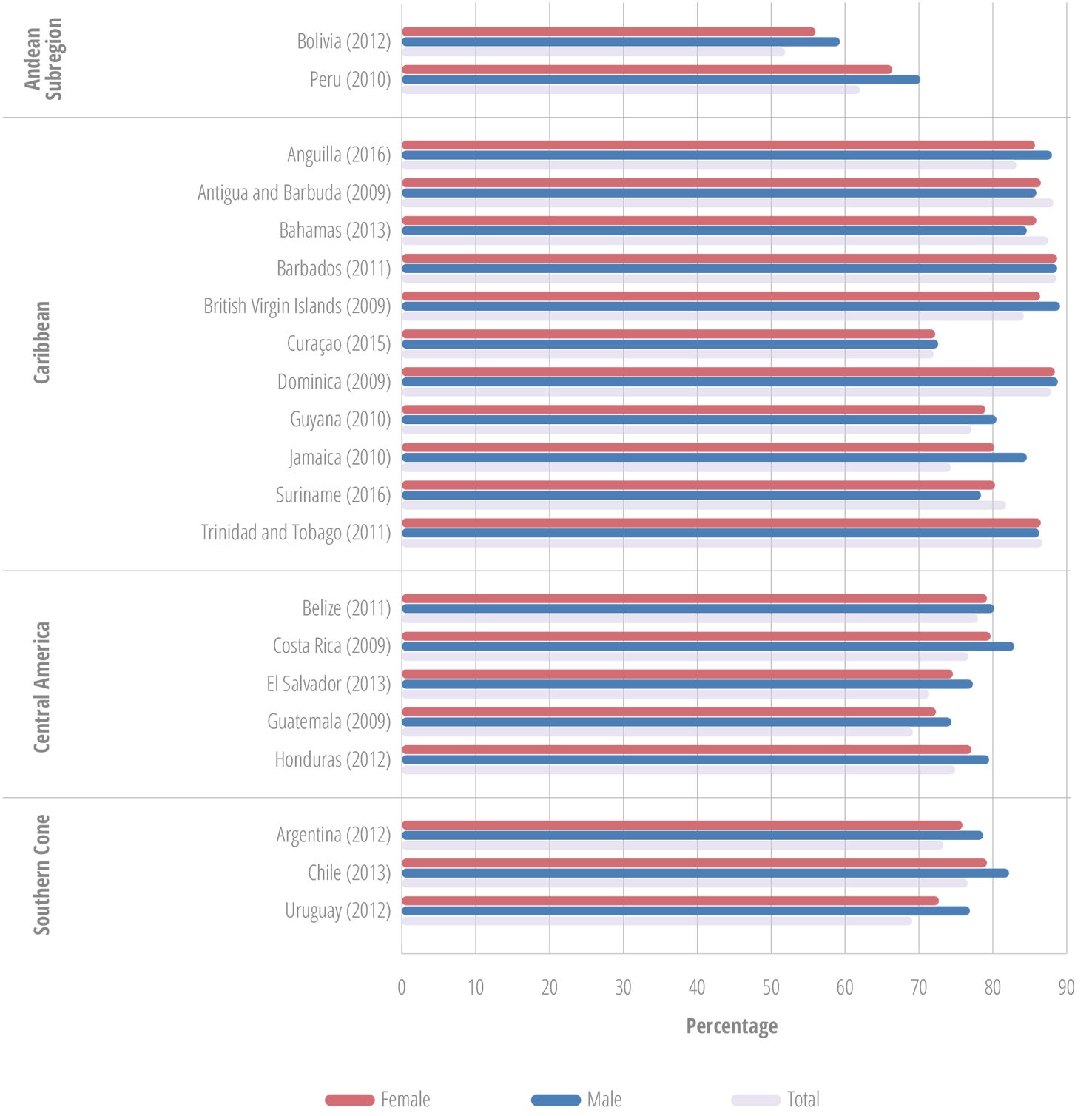

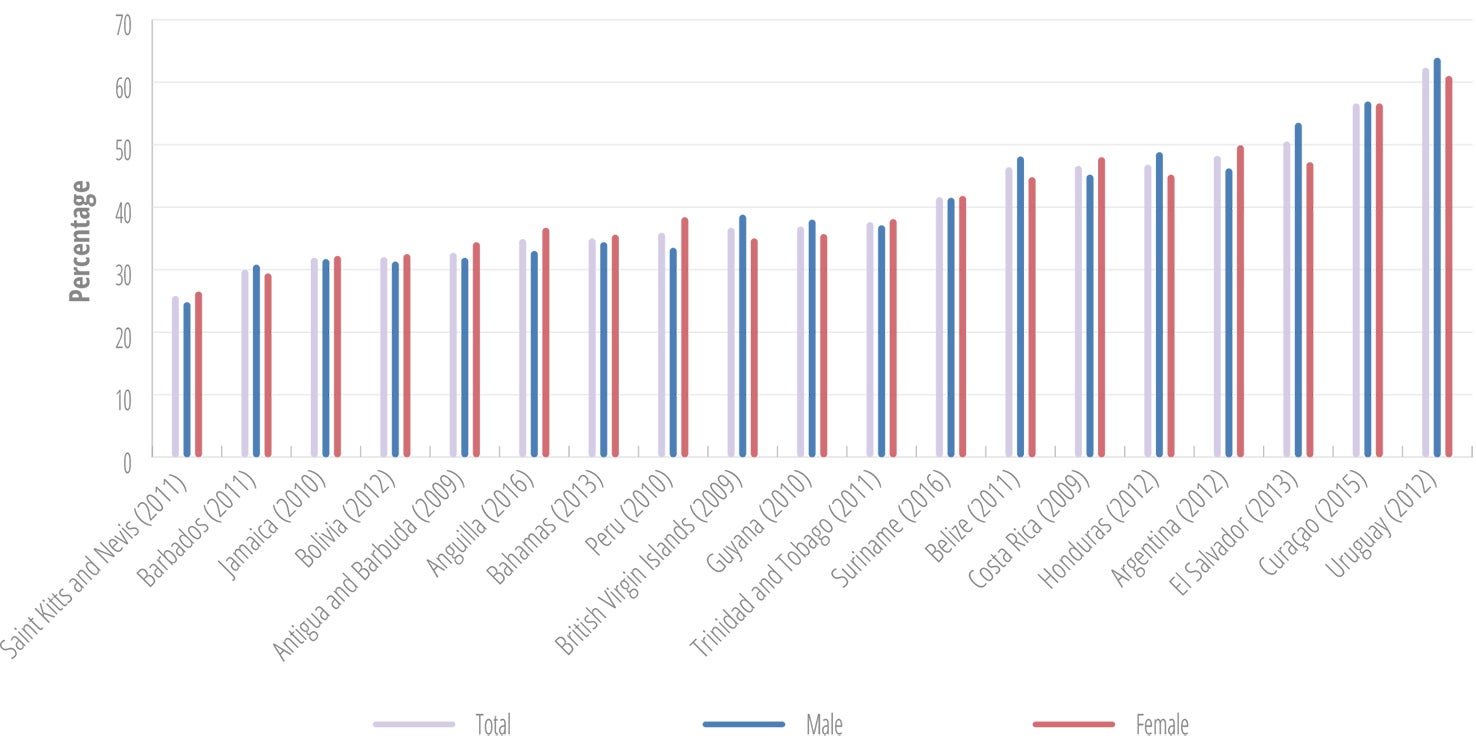

GSHS survey data shows variances between countries in current alcohol use (Figure II.14). The countries with the highest percentages of current alcohol use are Dominica (54%), Saint Lucia (54%), Jamaica (52%), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (51%), and Argentina (50%). While in most countries more males than females are current drinkers, the gender gap is narrow, and there are several countries with higher percentages of female current drinkers, including Argentina, Honduras, Antigua and Barbuda, Anguilla, Curaçao, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

a Students who had a drink in the 30 days prior to the survey.

The data also illustrate the early introduction of alcohol. Among the students who reported having had at least one drink during their lifetime – other than a few sips – the majority had the first drink prior to age 14 (Figure II.15). The males tend to have a few percentage points higher proportions of early starters.

a Among students who ever had at least one drink, apart from a few sips.

The percentage of lifetime alcohol users who report that they have been “really drunk” at least once ranged from 10% to over 30%. While in most countries more males than females are in this category, several countries, including Uruguay, Chile, Cayman Islands, Anguilla, and British Virgin Islands, had more females in this category (Figure II.16).

a Among students who ever had at least one drink, apart from a few sips.

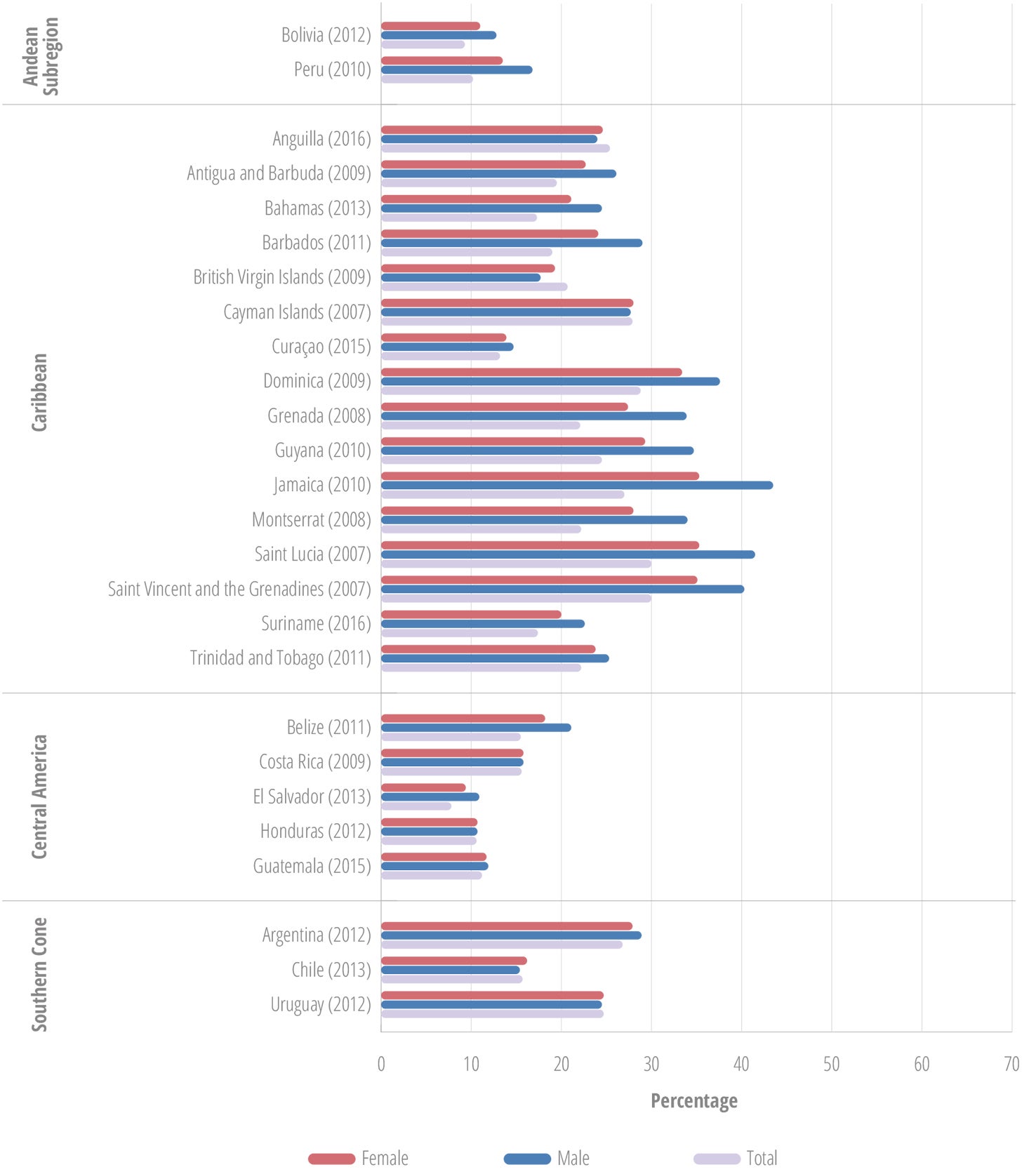

Figure II.17 provides an overview of the ways the students obtained alcohol in the 30 days preceding the GSHS survey, showing striking differences among the subregions. In the Caribbean, home and family were most frequently named as sources, while in Central America, friends were the most frequent source. According to this information, efforts to curtail alcohol use among adolescents should target family and friends as important sources for adolescents to obtain alcohol.

a Among students who ever had at least one drink, apart from a few sips.

From the 18 countries with data on past-month alcohol use among secondary school students in OAS reports published in 2011 and in 2015 (86, 87), 14 showed reductions in past-month alcohol use among females and males. The other four countries—Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines—reported increased past-month alcohol use.

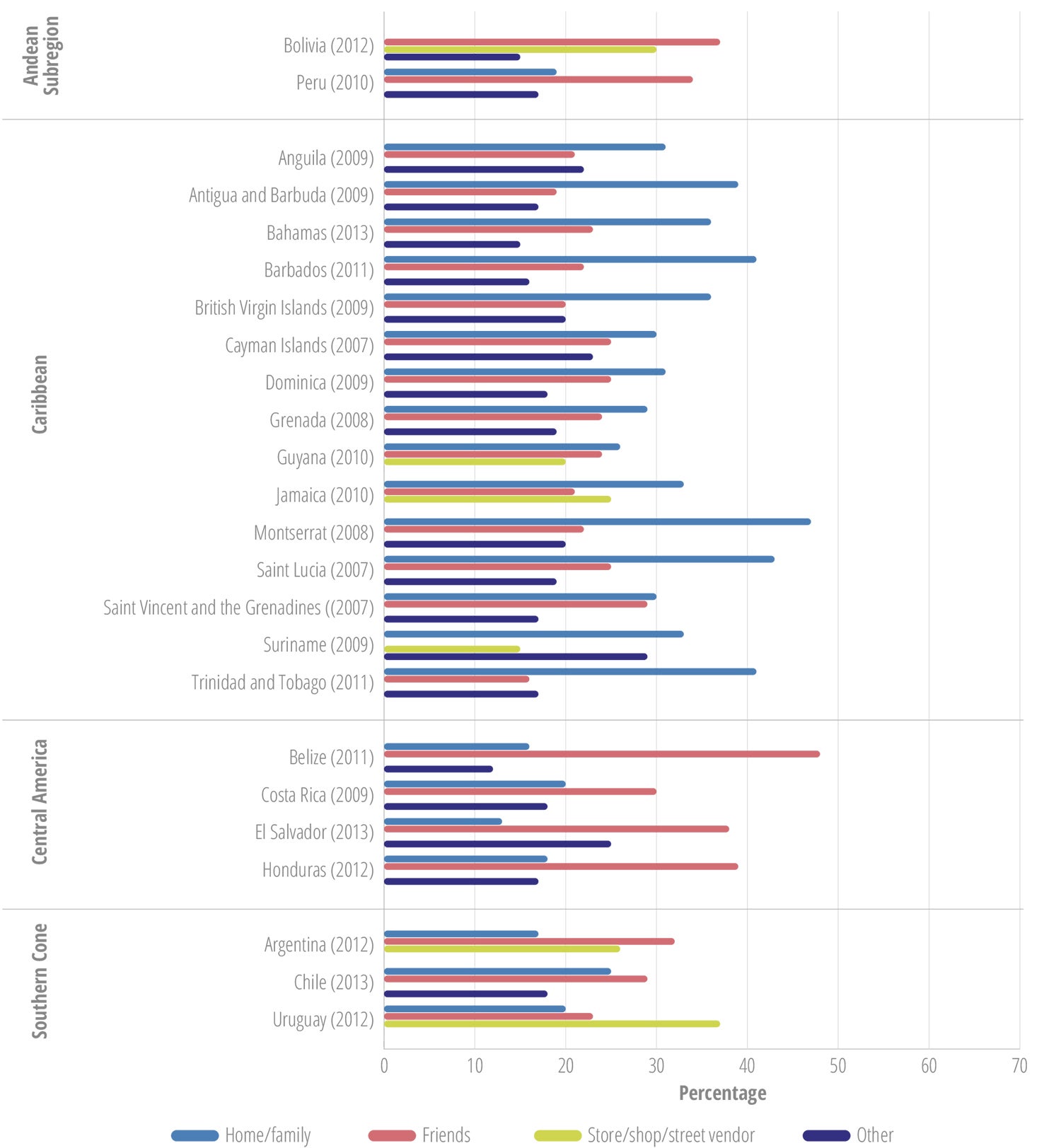

Tobacco

The use of tobacco is not limited to smoking of cigarettes, but includes chewing, sniffing, application to the skin, and placing tobacco between the teeth and gums (smokeless tobacco use). Based on the data from the most recent Global Youth Tobacco Surveys (GYTS), the percentage of current tobacco users among adolescents aged 13-15 years in the Americas ranged from 1.9% in Canada to 28.7% in Jamaica (Figure II.18). With the exception of Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador, more male students than female students reported recent tobacco use (88).

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control was developed by countries in response to the globalization of the tobacco epidemic. The treaty provides guidance for tobacco control, including measures to address the supply side as well as the demand side of tobacco (89). The treaty recommends specific measures to limit young persons’ access to tobacco products, including by prohibiting the sale of tobacco products to or by persons under the age set by domestic or national law, or younger than 18 years. The WHO and PAHO recommend evidence-based interventions to reduce adolescent tobacco use and exposure (Annex II.D2).

Other psychoactive substances

The use of other psychoactive substances such as marijuana, inhalants, and cocaine, remains relatively low among young people in the Americas. However, careful consideration must be given to trends in the use of these substances.

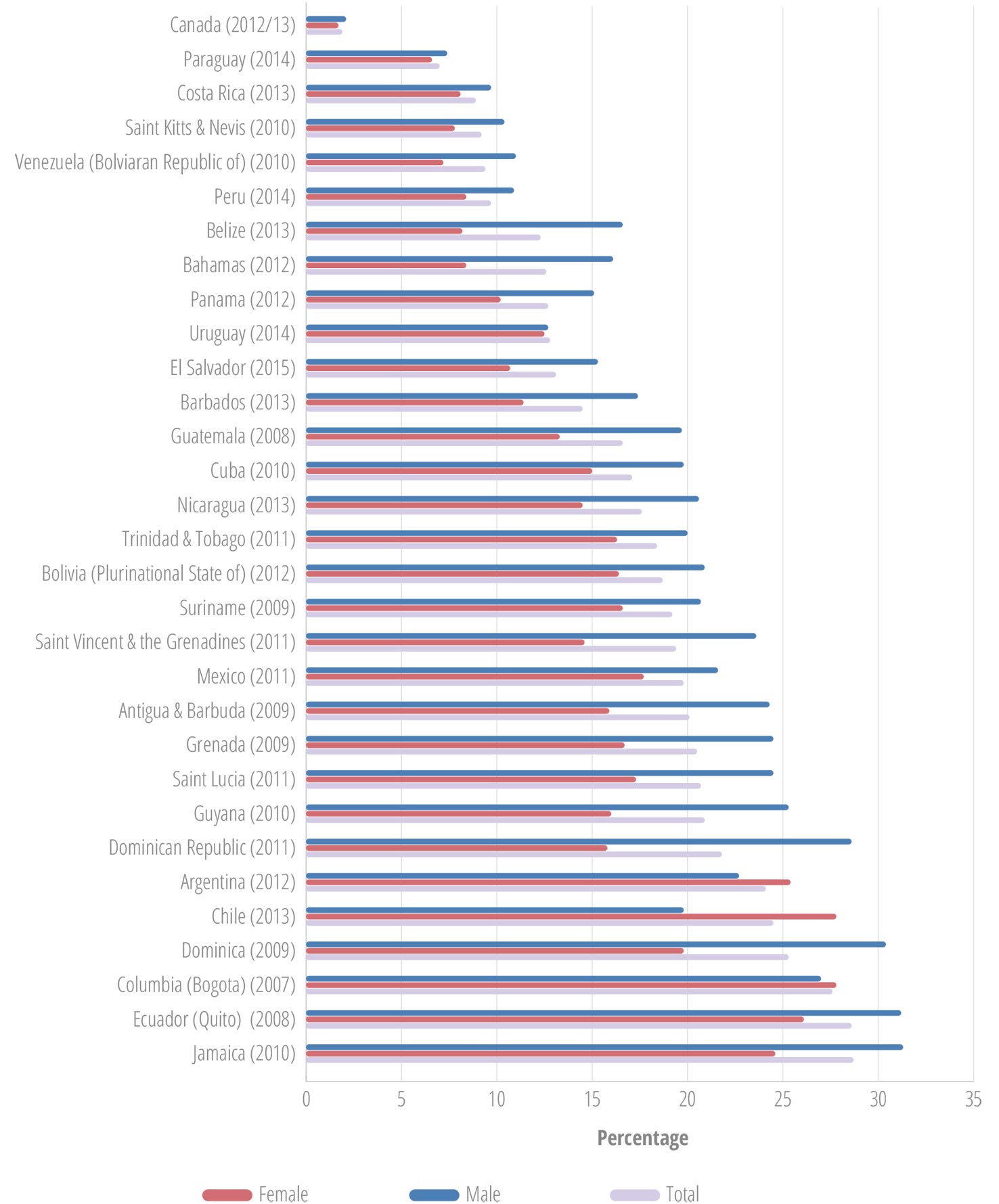

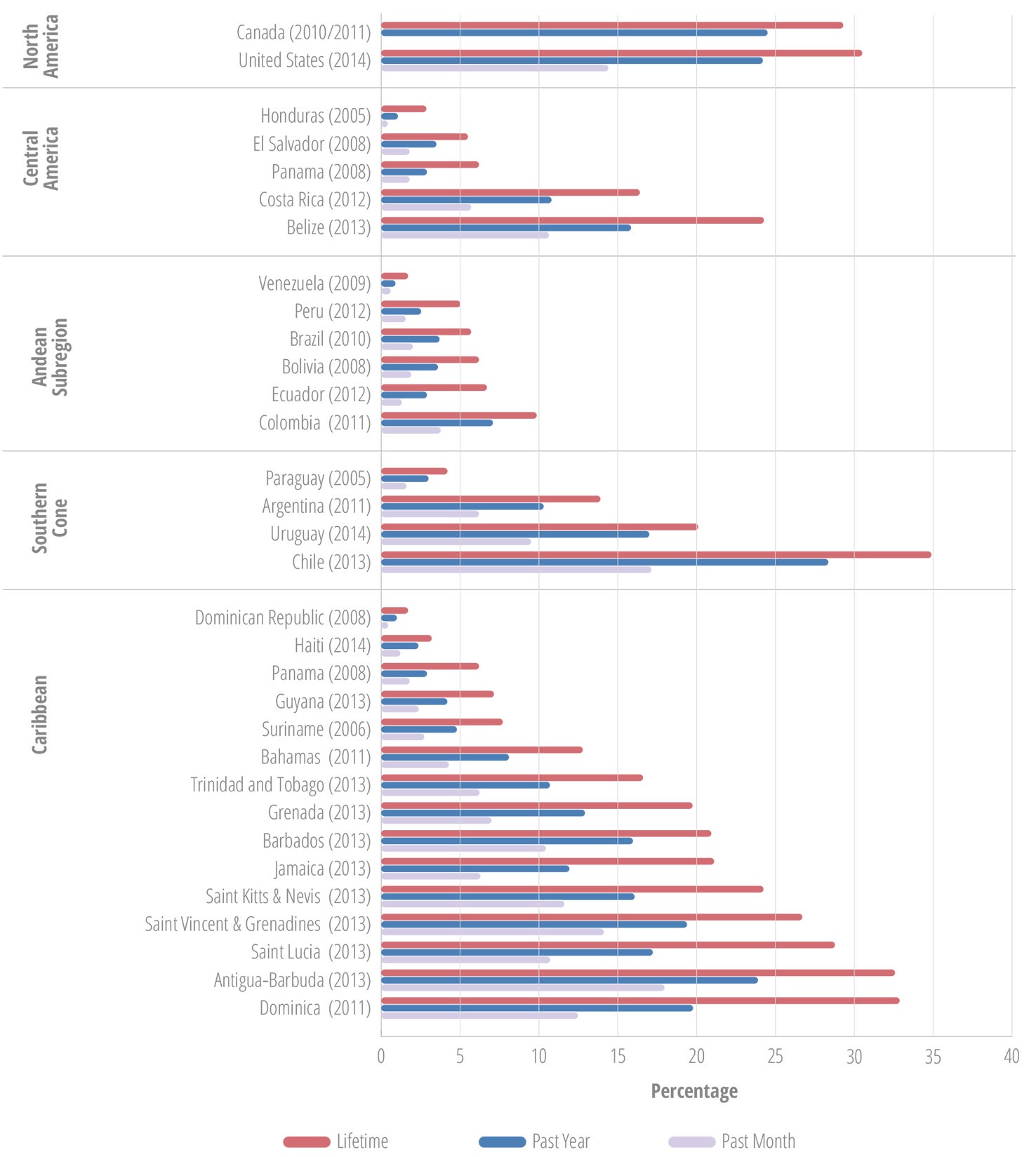

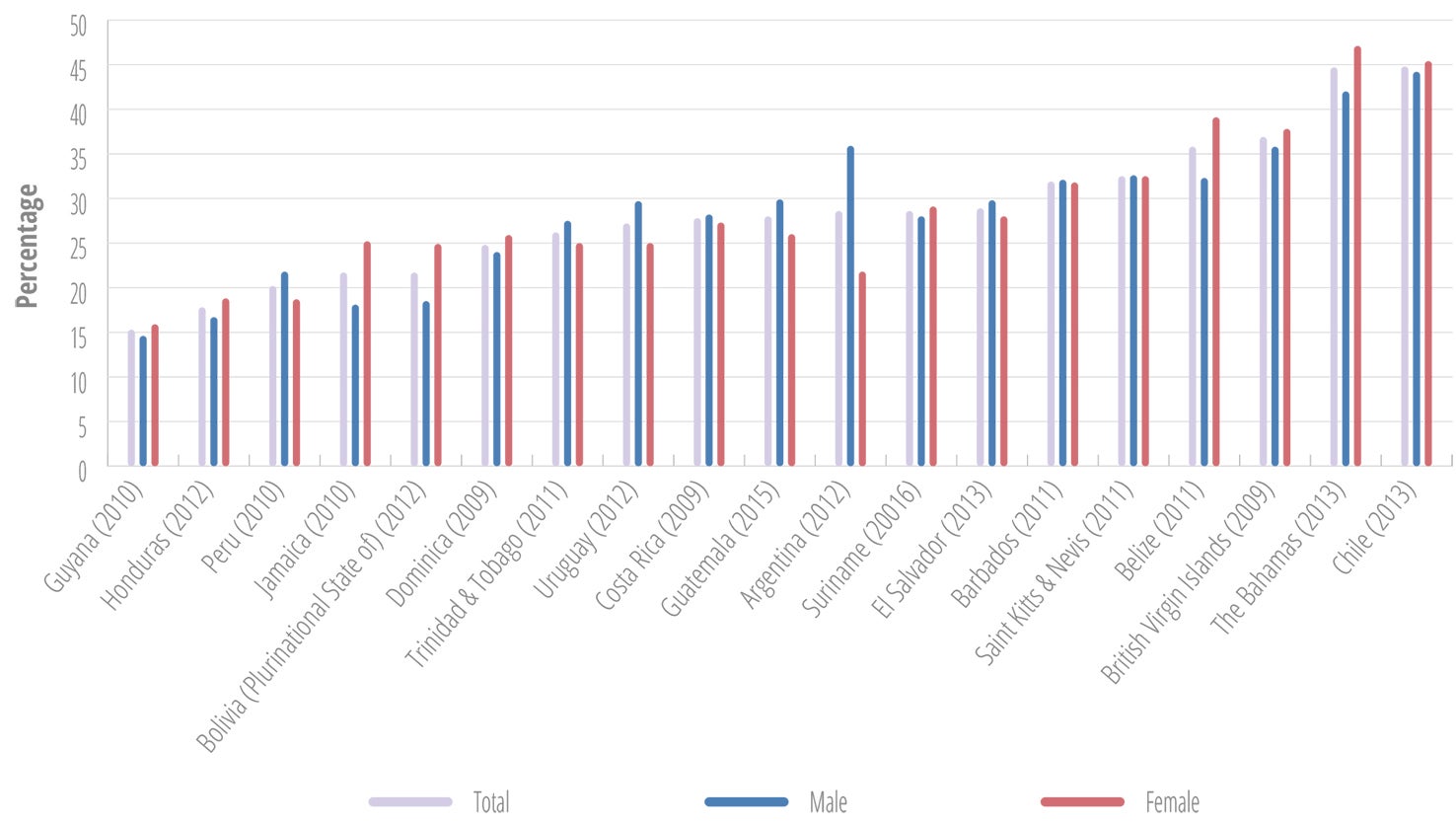

GSHS data for Latin America and the Caribbean suggest early initiation of the use of these psychoactive substances, with marijuana as the one most commonly used, after tobacco and alcohol (81), and with marked differences between countries. Reported lifetime marijuana use in adolescents aged 13-15 years in the GSHS ranged from 3% in Bolivia to 16% in Anguilla (81). The OAS data showed similar trends for the use of marijuana by secondary school students, ranging from 1.7% in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela to 34.9% in Chile (Figure II.19). In most countries, reported lifetime and recent (past-month) marijuana use was higher among males, with close to or more than twice as many males as females having used marijuana within the past year (87).

Inhalants used to cause psychoactive or mind-altering effects include solvents, aerosols, gases, and nitrates. Most of these substances are common household items, and are therefore not controlled. The past-year use of inhalants among countries of the Region ranged from 0.5% to 11.0%, and past-month use from 0.2% in Venezuela to 7.1% in Barbados (87). The countries with the highest past-month use at the last OAS survey were Barbados, Grenada, and Saint Lucia (87). Of the countries with two data points, 18 of them showed an increase in the past-month use, and 8 showed a decrease. Some of the decreases were quite substantial, for instance, in Jamaica from 9.5% in 2006 to 4.2% in 2013, in Brazil from 10.0% in 2004 to 2.2% in 2010, and in Guyana from 7.0% in 2007 to 2.8% in 2013 (87).

Lifetime use of cocaine in the secondary school population ranged from 0.6% in Venezuela to 6.0% in Chile, with most countries in the range of 1% to 3% (87). Past-year use ranged from 0.3% in Venezuela to 3.6% in Chile, with most countries in the 1%-2% range. Past-month use ranged from 0.1% in Suriname to 1.7% in Chile.

II.4 Sexual and reproductive health

Adolescence is a critical life stage for sexual and reproductive health (SRH), due to the rapid physical, hormonal, and emotional changes during puberty, including menarche for girls and their new biological capacity to reproduce. Good adolescent SRH requires the development of a positive, respectful, responsible approach to sexuality and sexual relations; the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences free of coercion, discrimination, and violence; and the freedom to responsibly decide if, when, and how often to reproduce.

Box II.3: Regional adolescent and youth health goal 5

Ensure sexual and reproductive health

- Reduce the percentage of births by mothers 15-19 years old

- Increase the percentage of condom use during last high-risk sex among those 15-24 years old

- Increase contraceptive prevalence among adolescents and youth ages 15-24 years

- Reduce the prevalence of HIV-infected pregnant women aged 15-24 years

- Reduce the estimated number of adolescents and youth 15-24 years of age living with HIV

- Reduce the specific fertility rate of adolescents aged 15-19 years

Source: (4)

Promoting and protecting adolescent SRH includes ensuring optimal access to information and education and appropriate health services (including safe, effective, affordable, acceptable contraception), as well as protection from coerced and forced sex. Undesired outcomes include sexually transmitted diseases, HIV, unplanned pregnancies, and unsafe abortions. Any of these can have repercussions that extend beyond adolescence and across the life course, even spilling over into the next generation.

Sexual initiation

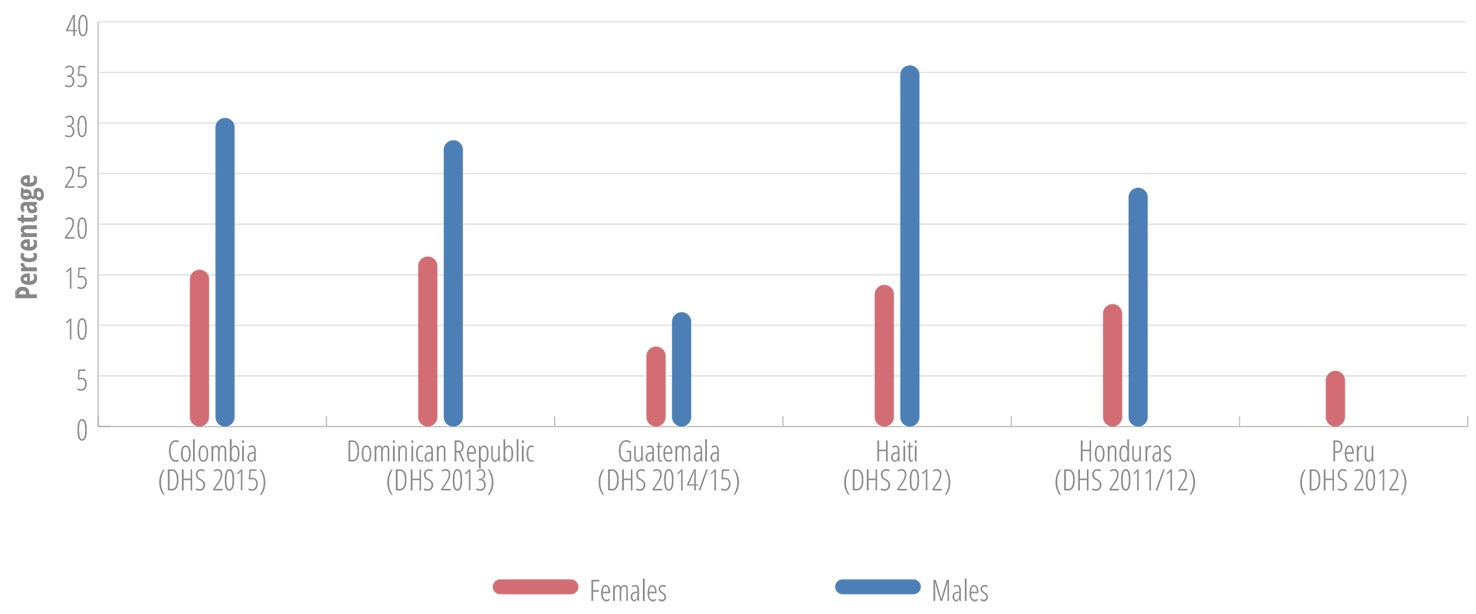

Early sexual initiation has been identified as a risk factor for adverse SRH outcomes, especially in the absence of comprehensive and supportive SRH services. The rate of early sexual initiation among adolescents differs noticeably among countries and between the sexes, as shown in Figure II.20. The percentage of early initiators is consistently higher among males.

The GSHS data showed similar results. Among 14 LAC countries with data for the 2010-2016 period, the percentage of students aged 13-15 years old who had ever had sexual intercourse ranged from 18.9% in El Salvador to 33.5% in Barbados (81), also with consistently higher percentages of male early initiators, in several countries up to twice as many (81).

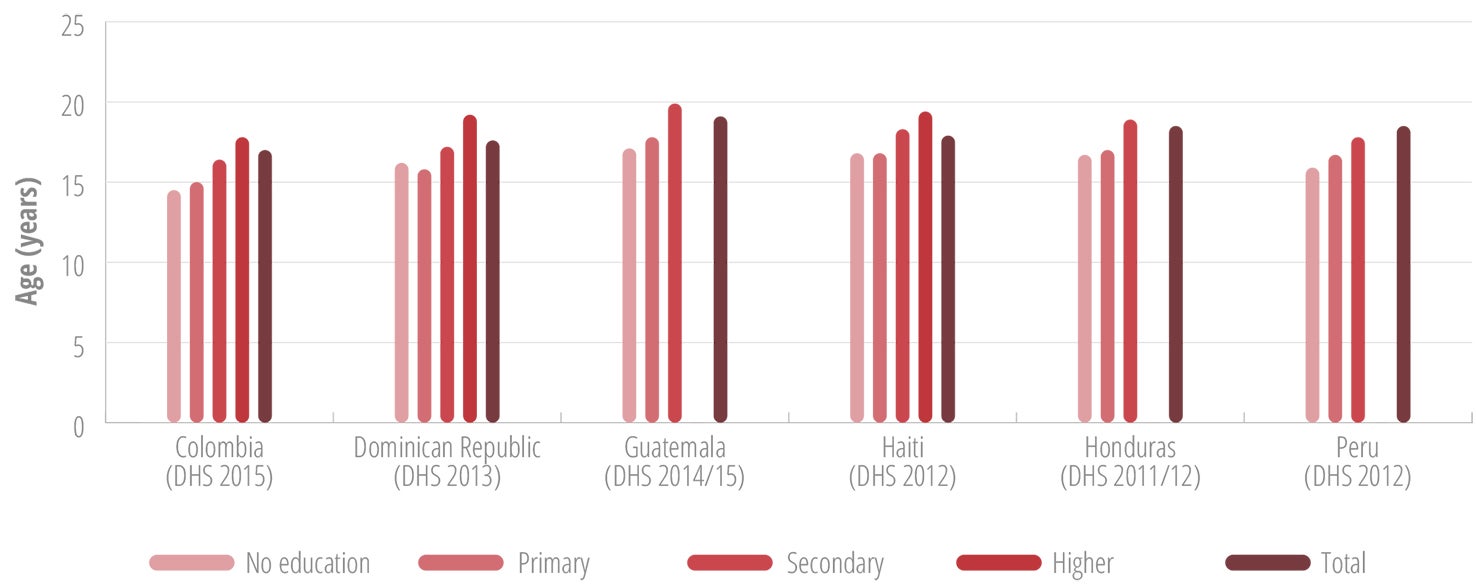

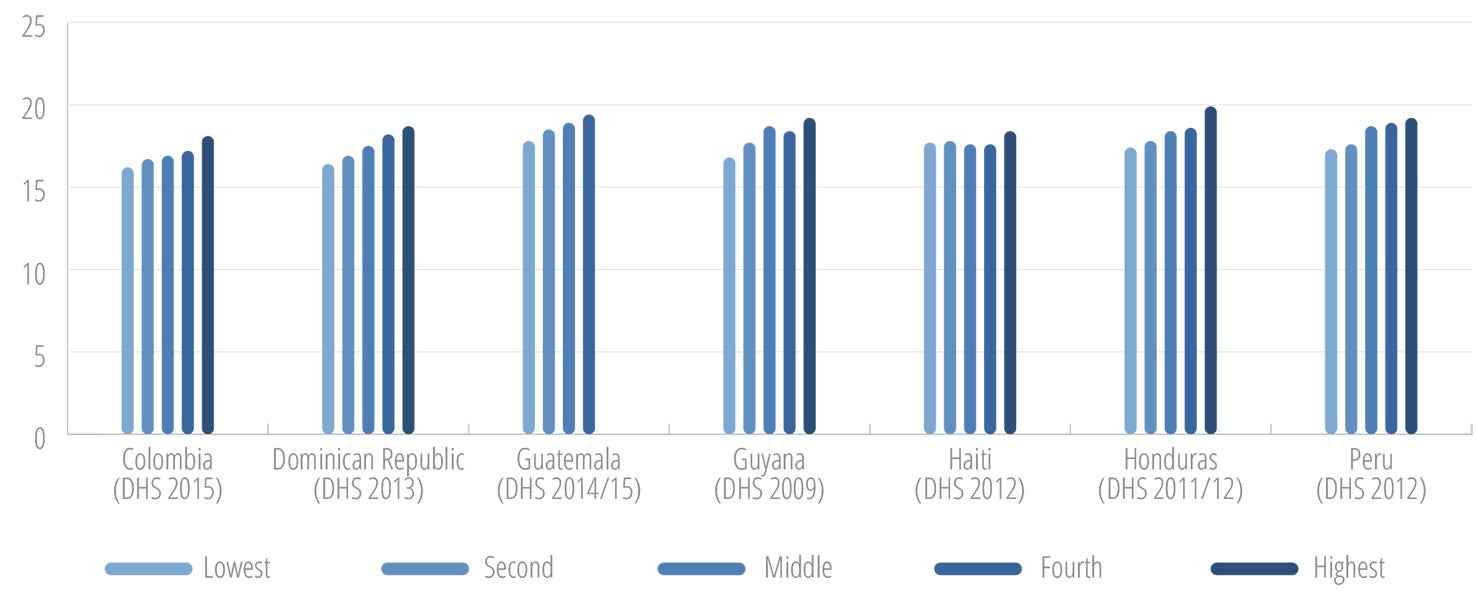

The available Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data also indicates a relationship between age of sexual initiation and both education (Figure II.21) and income level (Figure II.22) (91).

Females with lower levels of education and those from lower wealth quintiles had a lower median age of sexual initiation, as compared with their counterparts with more education or higher income.

Adolescent pregnancy

Although adolescence is a pivotal period for the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) of both boys and girls, girls bear disproportionate risks for adverse SRH outcomes, including early pregnancy. Maternity-related causes are now the leading cause of adolescent girl mortality on global level (6). Other physical consequences and risks of early pregnancy include damage to the pelvic floor, preeclampsia, eclampsia, ruptured membranes, and premature delivery (92-94). In addition to physical consequences, early pregnancy has various potential mental health implications, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress (especially when the pregnancy is the result of sexual violence), suicidal thoughts and attempts, and suicide deaths (92-94).

Adolescent pregnancy is linked to poverty, social exclusion, sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), and early marriage/union. Consequently, adolescent pregnancy disproportionately affects girls who are already marginalized, and it also has major long-term consequences for their educational and employment opportunities (92-95). As a result, adolescent pregnancy contributes to the maintenance of intergenerational cycles of poverty, exclusion, and marginalization, as children born to adolescent mothers are themselves at elevated risk of poverty and poor health outcomes.

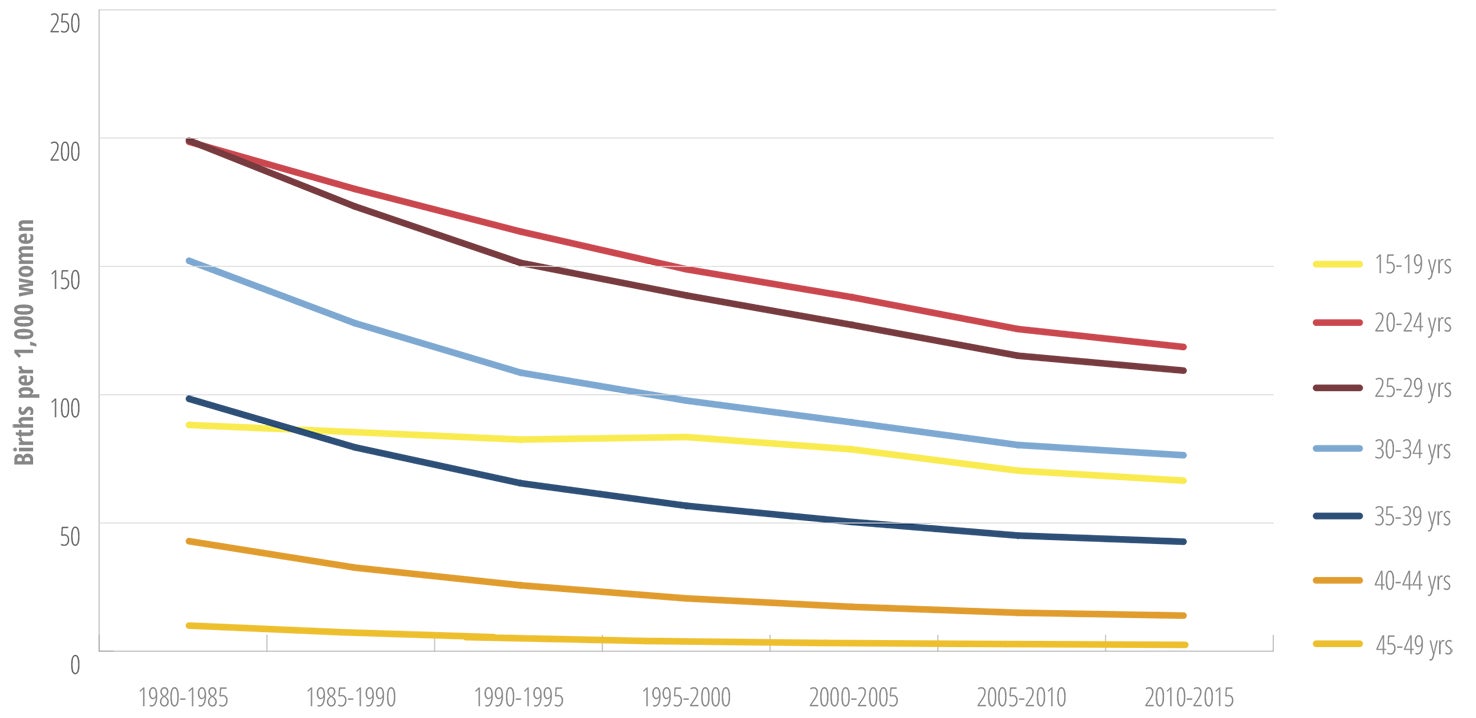

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has the second-highest adolescent fertility rate in the world, estimated at 66.5 births per 1,000 girls 15-19 years old for 2010-2015, compared to 46 births per 1,000 girls in the same age group worldwide (96). Trends over time indicate the adolescent fertility rate remained stable in LAC from 1990 to 2000, followed by a slow downward trend over the next 15 years. In contrast, there has been a much steeper decline in the total fertility rate in women in older age groups in LAC (Figure II.23) (96). Currently, an estimated 15% of all pregnancies in LAC occur among girls younger than 20 years old (97).

In the Americas, there are substantial differences in the adolescent fertility rate among subregions, countries, and subgroups in countries. As presented in Figure II.24, Central America has the highest adolescent fertility rate, followed by South America. The figure also indicates that South America has seen the slowest decline in adolescent fertility rates of any of the subregions (96).

Meanwhile, adolescent fertility rates in Canada and the United States are below the global average and have been declining steadily over the past decade. The United States recently reported a record decline in adolescent fertility in all racial and ethnic groups, falling 8% from 2014 to 2015, to a historic low of 22.3 births per 1,000 females 15-19 years old. In this same age group, similar or greater declines were reported for Hispanic (8%) and non-Hispanic black females (9%) (98).

The estimated country-level adolescent fertility rates range from 11.3 births per 1,000 girls in Canada to 100.6 per 1,000 girls in the Dominican Republic. The majority of countries with the highest estimated adolescent fertility rates are in Central America, with the highest rates in Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Panama. In the Caribbean, the Dominican Republic and Guyana have the highest estimated adolescent fertility rates. In South America, Bolivia and Venezuela have the highest rates (Table II.3).

| Subregion/Country | 1980 to 1985 | 1985 to 1990 | 1990 to 1995 | 1995 to 2000 | 2000 to 2005 | 2005 to 2010 | 2010 to 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | 48.9 | 50.4 | 56.3 | 48.4 | 40.5 | 37.3 | 28.3 |

| Canada | 24.9 | 23.2 | 25.1 | 20.1 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 11.3 |

| Mexico | 97.8 | 88.5 | 79.8 | 84.1 | 76.7 | 71.2 | 66.0 |

| United States of America | 51.6 | 53.3 | 59.6 | 51.3 | 43.2 | 39.7 | 30.0 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 88.2 | 85.4 | 82.5 | 83.5 | 78.7 | 70.4 | 66.5 |

| Caribbean | 91.6 | 87.8 | 81.8 | 77.8 | 68.5 | 64.7 | 60.2 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 61.6 | 59.6 | 66.1 | 68.7 | 62.8 | 55.5 | 49.3 |

| Aruba | 53.3 | 52.0 | 49.1 | 47.3 | 41.1 | 33.4 | 26.6 |

| The Bahamas | 85.6 | 69.8 | 69.6 | 61.9 | 44.0 | 39.4 | 34.2 |

| Barbados | 70.8 | 49.9 | 57.9 | 52.0 | 49.1 | 47.9 | 46.9 |

| Belize | 151.2 | 131.6 | 121.7 | 106.3 | 91.2 | 76.2 | 69.7 |

| Cuba | 85.7 | 85.7 | 69.2 | 69.4 | 50.6 | 49.3 | 48.3 |

| Curaçao | 50.9 | 52.0 | 51.5 | 43.5 | 36.7 | 34.1 | 35.5 |

| Dominican Republic | 110.6 | 110.2 | 114.3 | 111.0 | 109.6 | 108.7 | 100.6 |

| French Guyana | 90.9 | 86.6 | 104.7 | 111.8 | 106.0 | 80.3 | 82.6 |

| Grenada | 100.6 | 99.2 | 83.5 | 61.5 | 51.2 | 42.4 | 35.4 |

| Guadeloupe | 41.3 | 34.9 | 25.8 | 21.8 | 20.1 | 19.5 | 17.2 |

| Guyana | 114.4 | 94.6 | 99.1 | 94.6 | 100.2 | 94.1 | 90.1 |

| Haiti | 86.1 | 78.3 | 69.9 | 61.8 | 52.5 | 46.4 | 41.3 |

| Jamaica | 129.2 | 112.8 | 103.4 | 94.5 | 82.4 | 73.5 | 64.1 |

| Martinique | 35.4 | 33.3 | 28.7 | 26.0 | 24.5 | 24.0 | 21.1 |

| Puerto Rico | 69.6 | 66.4 | 73.2 | 72.4 | 64.4 | 50.0 | 47.3 |

| Saint Lucia | 148.6 | 120.8 | 94.6 | 69.8 | 62.0 | 61.4 | 56.3 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 110.4 | 95.1 | 88.0 | 76.1 | 64.6 | 58.9 | 54.5 |

| Suriname | 77.8 | 71.2 | 65.3 | 59.9 | 55.2 | 51.3 | 48.1 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 85.2 | 72.1 | 56.1 | 44.3 | 38.4 | 38.1 | 34.8 |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 86.4 | 82.1 | 77.0 | 64.5 | 49.4 | 50.0 | 47.3 |

| Central America | 105.8 | 96.9 | 88.7 | 90.3 | 82.4 | 75.7 | 69.1 |

| Costa Rica | 97.1 | 95.3 | 91.8 | 83.2 | 69.8 | 64.5 | 59.1 |

| El Salvador | 119.5 | 108.2 | 98.7 | 91.1 | 85.3 | 76.7 | 66.8 |

| Guatemala | 138.5 | 126.8 | 120.6 | 113.8 | 104.2 | 93.2 | 84.0 |

| Honduras | 140.0 | 133.5 | 126.5 | 115.8 | 100.0 | 84.1 | 68.4 |

| Nicaragua | 154.0 | 160.1 | 146.2 | 125.2 | 113.2 | 104.7 | 92.8 |

| Panama | 111.1 | 102.6 | 92.5 | 94.0 | 85.9 | 81.9 | 78.5 |

| South America | 80.9 | 80.1 | 79.9 | 81.1 | 78.1 | 68.6 | 66.0 |

| Argentina | 74.2 | 73.4 | 73.2 | 69.8 | 65.0 | 60.6 | 64.0 |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 98.8 | 96.1 | 91.2 | 93.0 | 87.9 | 81.9 | 72.6 |

| Brazil | 79.8 | 80.6 | 80.0 | 83.6 | 80.9 | 70.9 | 68.4 |

| Chile | 66.0 | 65.6 | 63.6 | 60.8 | 54.5 | 52.7 | 49.3 |

| Colombia | 80.9 | 75.7 | 82.7 | 83.3 | 86.3 | 63.7 | 57.7 |

| Ecuador | 93.4 | 88.7 | 85.5 | 84.3 | 82.5 | 83.0 | 77.3 |

| Paraguay | 96.8 | 91.6 | 92.4 | 91.9 | 76.6 | 67.8 | 60.2 |

| Peru | 74.1 | 72.0 | 70.0 | 70.5 | 61.5 | 54.7 | 52.1 |

| Uruguay | 62.6 | 66.4 | 70.6 | 67.3 | 63.5 | 61.2 | 58.0 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 100.3 | 100.2 | 94.9 | 90.6 | 88.0 | 82.6 | 80.9 |

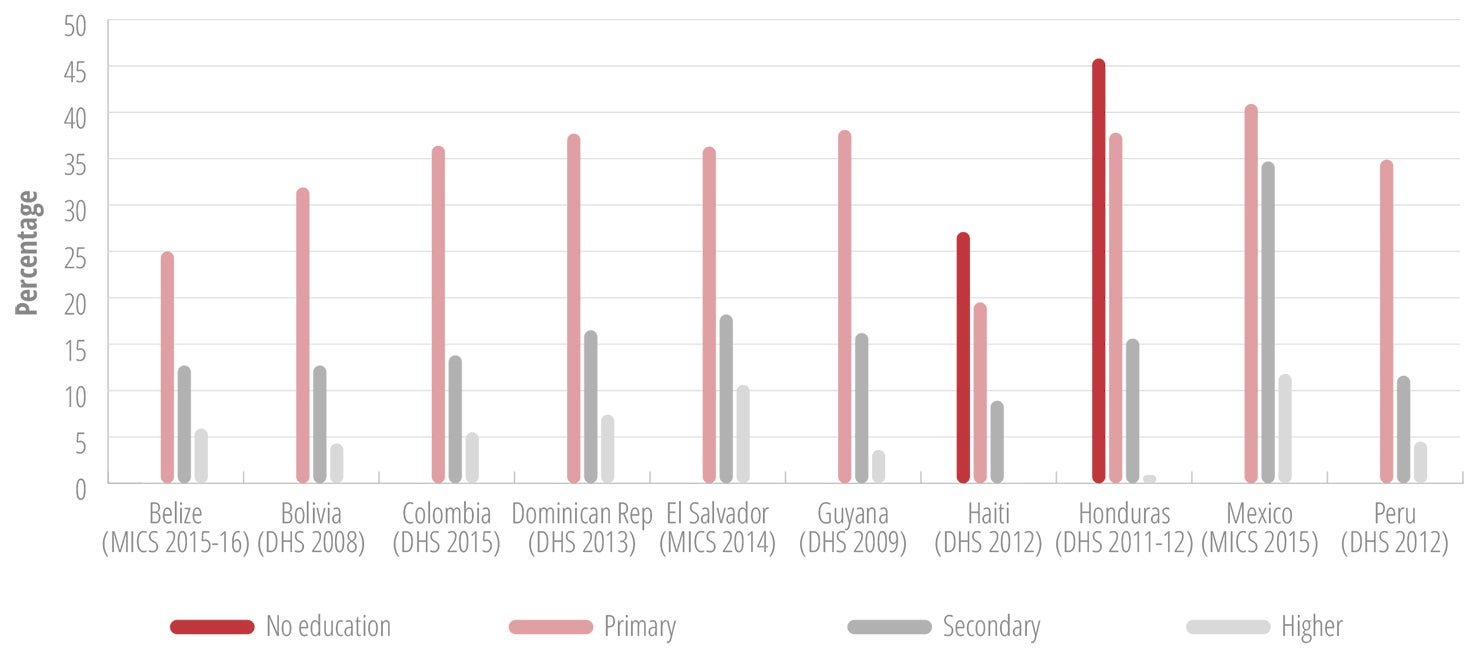

Adolescent girls with no education or only primary education may be up to four times more likely to initiate childbearing than are girls with secondary or higher education (Figure II.25).

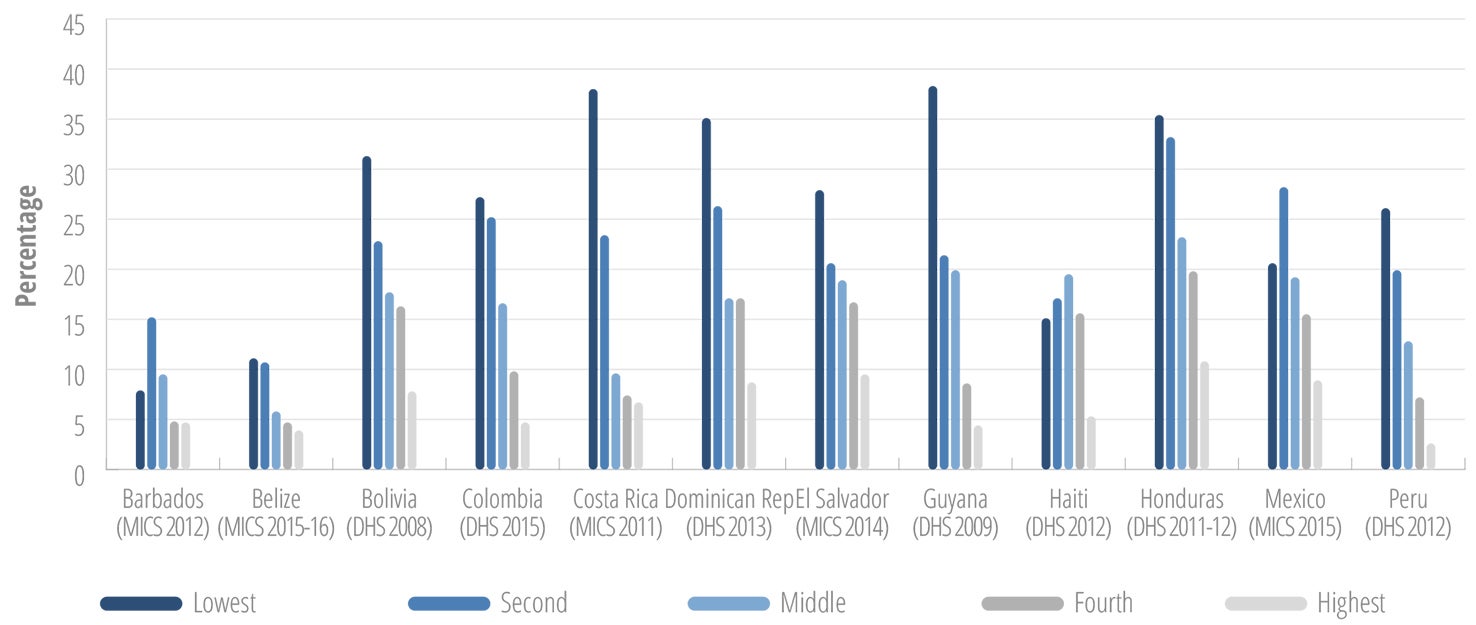

Similarly, girls from households in the lowest wealth index quintile are three to four times more likely to initiate childbearing, as compared to girls from the highest wealth index quintile (Figure II.26).

Census data in selected countries show that indigenous girls are also disproportionately affected by early pregnancy, with the highest percentages of adolescent mothers being among rural indigenous girls (Table II.4).

| Country (census year) | Age group (years) | Percentage of adolescent mothers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous | Nonindigenous | ||||||

| Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | ||

| Brazil (2010) | 15–17 | 10.6 | 22.9 | 18.7 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 6.8 |

| 18–19 | 26.8 | 46.9 | 39.4 | 18.2 | 26.6 | 19.5 | |

| 15–19 | 17.0 | 31.6 | 26.4 | 11.1 | 15.2 | 11.8 | |

| Costa Rica (2011) | 15–17 | 8.5 | 20.3 | 17.0 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 5.7 |

| 18–19 | 23.6 | 42.1 | 36.1 | 17.0 | 22.2 | 18.4 | |

| 15–19 | 15.2 | 28.7 | 24.7 | 10.0 | 12.6 | 10.8 | |

| Ecuador (2010) | 15–17 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 11.9 | 9.6 |

| 18–19 | 28.9 | 34.2 | 32.9 | 25.2 | 34.1 | 28.1 | |

| 15–19 | 17.4 | 18.5 | 18.3 | 15.0 | 20.3 | 16.8 | |

| Mexico (2010) | 15–17 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 7.1 | 6.0 |

| 18–19 | 23.4 | 27.4 | 25.3 | 20.6 | 25.8 | 21.6 | |

| 15–19 | 13.2 | 14.8 | 14.0 | 11.6 | 14.2 | 12.2 | |

| Panama (2010) | 15–17 | 16.9 | 20.5 | 19.6 | 5.7 | 8.9 | 6.7 |

| 18–19 | 38.8 | 54.2 | 49.7 | 19.1 | 28.6 | 21.7 | |

| 15–19 | 26.0 | 32.4 | 30.7 | 11.3 | 16.2 | 12.7 | |

| Uruguay (2010) | 15–17 | 6.0 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.6 |

| 18–19 | 20.2 | 25.8 | 20.4 | 16.9 | 21.9 | 17.1 | |

| 15–19 | 11.6 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 9.3 | 11.3 | 9.4 | |

Pregnancy in girls younger than 15 years

In general, data collection and reporting efforts related to adolescent pregnancy have focused on the age group 15-19 years, the age group for the international adolescent fertility indicator. Recently, the indicators proposed for the SDGs expanded international monitoring of adolescent pregnancy to the age group 10-19 years, disaggregated by 10-14 years and 15-19 years (100). This will hopefully result in increased efforts to generate data on pregnancies in girls younger than 15 years.

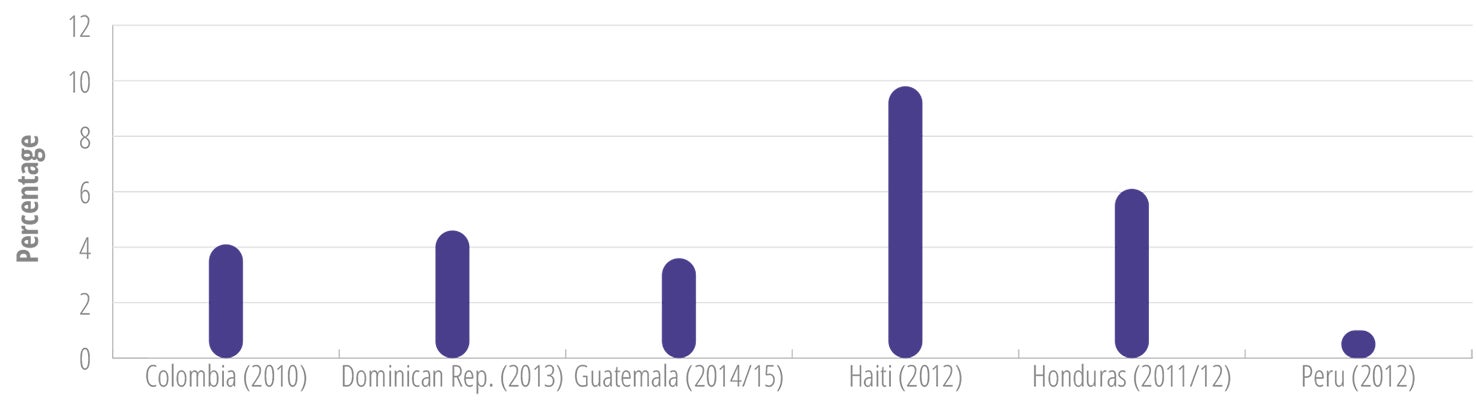

According to estimates of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), 2% of women of reproductive age in LAC had their first delivery before the age of 15, and LAC is noted as the only region in the world with a trend in more pregnancies among girls younger than 15 years (93). The bullet points below summarize the available quantitative and qualitative information on pregnancies in girls under 15 years of age in the Region of the Americas:

In 2015, Planned Parenthood Global published a report based on a multicountry study of the health effects of forced motherhood on girls 9-14 years old (101). The study was conducted in Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Peru. Pregnancy in girls under 15 years old had increased in all four of those countries. In Ecuador, according to census data, it had increased by 74% over the preceding decade. In Nicaragua, the number of pregnant women 10-14 years old increased 47% over 9 years, from 1,066 in 2000 to 1,577 in 2009. In Guatemala, the reported number of deliveries in girls 10-14 years old increased from 4,220 in 2013 to 5,100 in 2014. The girls tended to have low levels of education; some had never attended school. A large proportion of girls who had been in school had not returned to school postdelivery at the time of the follow-up interview (in Peru 77% dropped out; in Guatemala, 88%). The majority of the study participants suffered some type of complication with their pregnancy (63% in Peru, 71% in Ecuador). These complications included anemia, nausea/vomiting, urinary or vaginal infections, and more severe complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, membrane rupture, premature delivery, and postpartum hemorrhage, as well as mental health issues (55% in Peru, 91% in Ecuador, 100% in Nicaragua). Among the mental health issues were stress, fear, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress. In Peru and Nicaragua, 7% to 14% of the study participants reported having contemplated suicide during their pregnancy. In all the participating countries, having sex with a minor constituted a crime. Often the aggressors were persons close to the girls, such as a cousin, stepbrother, stepfather, biological father, or neighbor.

In 2016, the Latin American and Caribbean Committee for the Defense of Women’s Rights (CLADEM) published a report from a study in 14 countries3 titled Girls Mothers: Child Pregnancy and Forced Child Maternity in Latin America and the Caribbean (102). The study defined forced child pregnancy or maternity as a situation in which a minor under the age of 14 gets pregnant without having sought and/or without wanting the pregnancy, and interruption of the pregnancy is denied to her, made difficult, delayed, or hindered (102). In addition, The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) considers a forced pregnancy a crime against humanity or a war crime, depending on the context and characteristics of the case (102). The CLADEM study concluded that there were no specific data on pregnancies or abortions in girls under age 14 for any of the countries studied except El Salvador, where pregnancies in that age group were recorded. These records indicated that one-fifth to one-third of those pregnancies resulted in childbirth. In the other countries, statistics on pregnancies were drawn from delivery data and thus only reflected a subset of pregnancies in girls under 14, since child pregnancies often do not go to term. In all 14 countries, engaging in sexual relations with girls younger than 16 years is considered rape. With the exception of Brazil, Honduras, and Uruguay, kinship is considered an aggravating circumstance for statutory rape of minors or violation. However, only 6 of the 14 countries presented statistics on the denouncement of sexual violations of girls under age 14, and information regarding judicial investigation of the reported cases was scarce. In cases where denouncements were made, the level of impunity was very high, estimated to be up to 90%. In the countries that were studied, the abused girl’s mother is often investigated, detained, and prosecuted. Almost all the countries had some type of protocol on violence against women, but none had protocols, guidelines, or policies designed to address the problem of sexual violence against girls in a specific and comprehensive manner. Seven countries had State centers that provide care for and/or house pregnant adolescents and adolescent mothers, and all 14 countries had private entities that specialize in the care of pregnant young women. In some cases the pregnant girls were involuntarily housed in public or private institutions and forced to give their infants up for adoption. In the majority of the 14 countries, continuity of education was guaranteed by law, but about half of the pregnant girls interrupted their studies due to health problems, discriminatory prejudices against pregnant girls or child mothers, and other circumstances. An estimated 40% of this group gave up their studies forever.

3 Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Uruguay.

States Party to the Belem do Para Convention reports that were made to the Follow-up Mechanism to the Belem do Para Convention (MESECVI) during 2013-2016 regarding pregnancy in girls under 15 years (104) included the following information:

Paraguay reported that two of the births each day were to girls aged 10 to 14 years; that between 2009 and 2011, the number of live births to mothers between 10 and 14 years increased by 4%; and that 21.3% of the maternal deaths registered up through September 2012 were in the 10-14 age group.

Guatemala reported that in 2012, 13.3% of births corresponded to girls aged 14 years; that 9,450 abortions were registered among girls and adolescents; and that 80 girls died from causes linked to maternity.

In Peru, the reported percentage of mothers between 12 and 14 years was 12.5% in 2011 and 13.2% in 2012.

Chile reported that in 2011, with hospital discharges for pregnancy, birth, and puerperium that ended in abortion, 3,387 of them were among girls aged 10-19 years, and that 10% of maternal deaths were among girls and adolescents.

In 2014, Argentina registered 2,600 live births to mothers aged 10-14 years, with a survival rate of 87.4%.

For 2014, Mexico reported 11,012 births among girls younger than 14 years.

For 2015, Venezuela reported 5,399 live births among girls aged 10-14 years.

Costa Rica reported that from 1983 to 2000, the annual average number of births to mothers younger than 15 years was 460, and that since 2000, it has increased to an average of 500 per year.

Honduras reported that in 2015, 33,035 deliveries were among girls aged 10-19 years, of which 845 were to girls 10-14 years old.

As mentioned, sexual violence is of critical importance when it comes to adolescent girls' SRH, as adolescent girls may be particularly vulnerable to experience sexual violence perpetrated by intimate partners or others in their environment, including family members. Figure II.27 provides a snapshot of females in the age group 15-19 years, reporting having experienced sexual violence.

Maternal mortality is an important cause of death in girls and young women in the Region, and each year around 2,000 females aged 10-24 die from maternal causes (Table II.5). Although several countries have been able to provide good-quality maternal health care, adolescents (especially those under 15) continue to face an elevated risk of maternal mortality. This is a result of exposure to biological factors, such as insufficiently matured reproductive systems, and to socioeconomic and geographic factors, such as poor health care access in remote rural areas, racial/ethnic minority bias, stigma, and poverty.

| Year (no. of countries reporting) | Ranka (#) | Number of deaths | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-19 years | 15-24 years | 10-19 years | 15-24 years | |

| 2009 (45 reporting) | #5 | #4 | 865 | 2,225 |

| 2010 (43 reporting) | #5 | #4 | 784 | 1,851 |

| 2011 (39 reporting) | #5 | #4 | 830 | 1,920 |

| 2012 (39 reporting) | #6 | #4 | 778 | 1,894 |

| 2013 (37 reporting) | #6 | #4 | 748 | 1,802 |

| 2014 (26 reporting) | #6 | #4 | 577 | 1,404 |

a Rank in the leading causes of death in the age group in the specified year.

Due to the lack of progress in the reduction of adolescent pregnancy, PAHO, UNFPA, and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) held a technical consultation in August 2016 with global, regional, and country-level stakeholders to take stock of the situation and agree on strategic approaches and priority actions to accelerate progress (41, 105). The meeting pinpointed key factors that contribute to adolescent pregnancy in LAC. These included young women’s lack of knowledge about their sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), poor access to and inadequate use of contraceptives, restrictive laws and policies, limited education and income, sexual violence and abuse, early unions, and unequal gender relations (41, 105). The meeting participants also identified the following seven priority actions to accelerate the reduction of adolescent pregnancy in LAC (41, 105):

- Make adolescent pregnancy, its drivers and impact, and the most affected groups more visible with disaggregated data, qualitative reports, and stories.

- Design interventions targeting the most vulnerable groups, ensuring the approaches are adapted to their realities and address their specific challenges.

- Engage and empower youth to contribute to the design, implementation, and monitoring of strategic interventions.

- Abandon ineffective interventions and invest resources in proven interventions.

- Strengthen intersectoral collaboration to effectively address the drivers of adolescent pregnancy in LAC.

- Move from boutique projects to large-scale and sustainable programs.

- Create an enabling environment for gender equality and adolescent SRHR.

Contraceptives

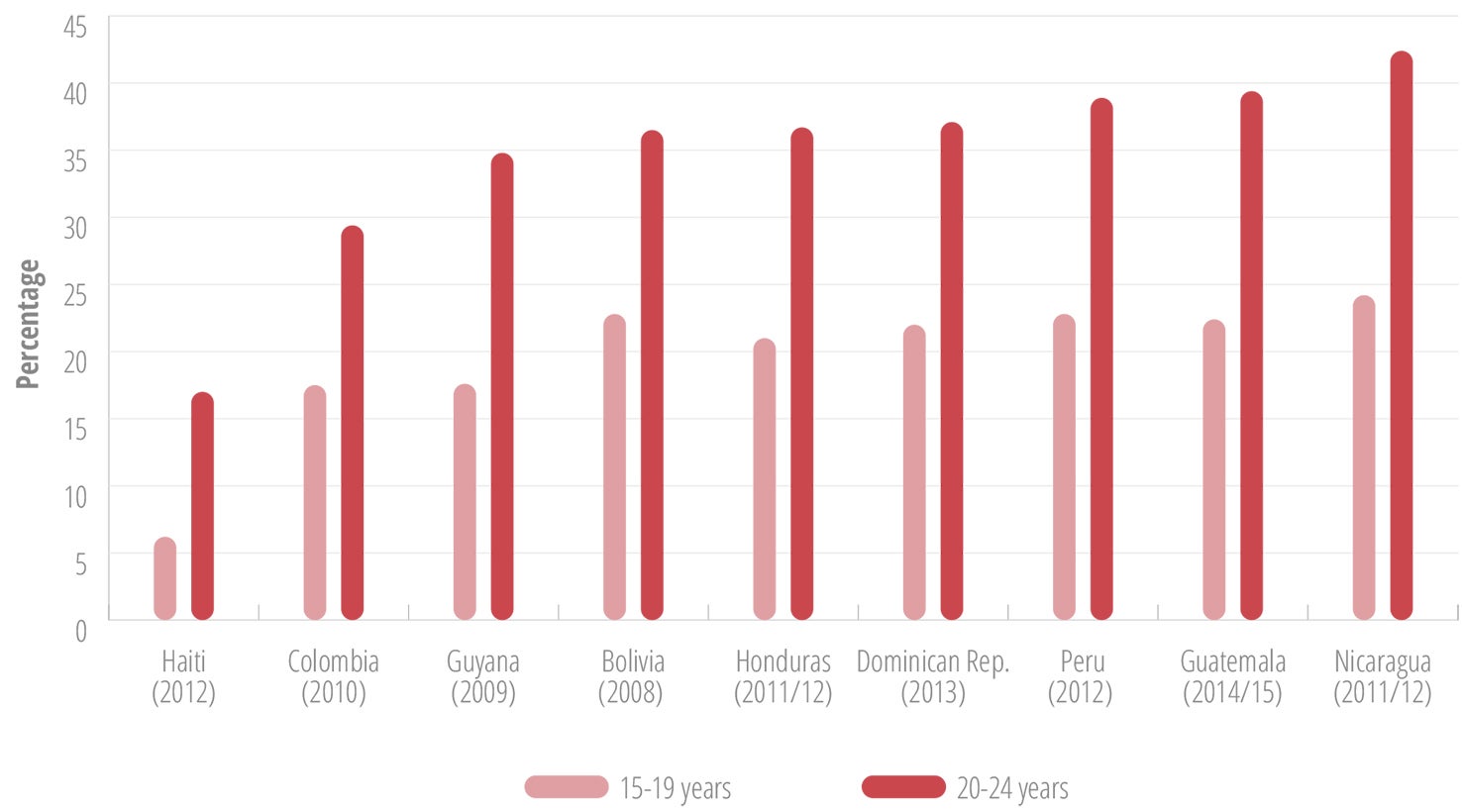

Contraceptive prevalence is defined as the percentage of women aged 15-49 who are married or in a union who are using a contraceptive method. Unmet need for contraception is defined as the percentage of women aged 15-49 currently married or in a union who are fecund and want to space births or limit the number of children they have and who are not currently using contraception (106). As a result of these definitions, much of the data available on contraceptive prevalence and unmet need is for the age group 15-49 years. That provides an overall picture of contraceptive use and unmet need, but it does not reflect the situation among young people, as contraceptive prevalence is generally lower and unmet need higher among younger women. However, this is changing, and increasingly surveys such as the DHS, which are supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the MICS, which are assisted by UNICEF, are calculating this data disaggregated by subgroups, including the 15-19 years and 20-24 years age groups. Nevertheless, these indicators and data fail to capture young women who are not married or in union but who are sexually active and wishing to prevent pregnancy. Table II.6 provides an overview of the contraceptive prevalence in selected LAC countries, as measured with DHS or MICS surveys.

| Country (year and study) | 15-19 years | 20-24 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current use of any modern method of contraceptive | Unmet need | Current use of any modern method of contraceptive | Unmet need | |

| Argentina (2012 MICS) | 32.8 | NAa | 58.4 | NA |

| Barbados (2012 MICS) | 51.4 | 37.3 | 50.1 | 33.7 |

| Belize (2011 MICS) | 33.8 | 30.8 | 47.9 | 25.8 |

| Bolivia (2008 DHS) | 6.1 | 37.9 | 21.9 | 27.2 |

| Colombia (2015 DHS) | 28.5 | 19.3 | 59.8 | 11.7 |

| Costa Rica (2011 MICS) | 64.1 | 19.7 | 75.5 | 9.2 |

| Cuba (2011 MICS) | 67.0 | 11.2 | 75.3 | 9.2 |

| Dominican Republic (2013 DHS) | 51.7 | 21.4 | 56.6 | 41.5 |

| Guatemala (2014/15 DHS) | 7.7 | 21.9 | 26.2 | 19.8 |

| Guyana (2009 DHS) | 13.9 | NA | 33.4 | 30.1 |

| Honduras (2011/12 DHS) | 14.1 | 17.7 | 37.7 | 13.1 |

| Haiti (2012 DHS) | 8.2 | 35.3 | 23.2 | 56.6 |

| Peru (2012 DHS) | 10.2 | 19.3 | 37.3 | 13.9 |

| Saint Lucia (2012 MICS) | 57 | NA | 32.0 | NA |

| Suriname (2010 MICS) | NA | 37.0 | NA | 26.0 |

Condom use

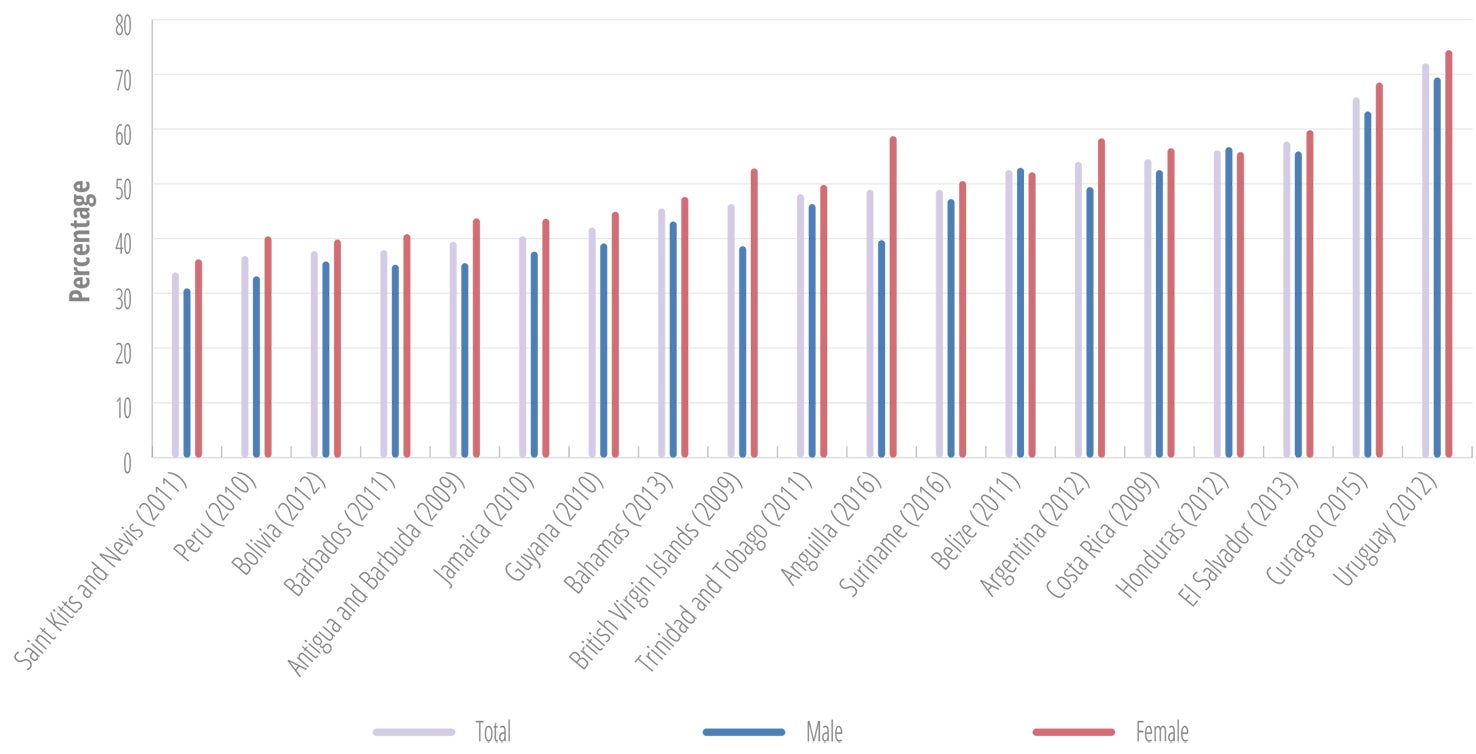

Adolescence is a life stage of rapid physical, emotional, and social development, characterized by increasing experimentation with adult roles, and development of behavioral patterns, including sexual behaviors, that may last throughout the life course. If used consistently and correctly, condoms can prevent unwanted pregnancy and the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during adolescence and beyond. Given that benefit, encouraging correct and consistent condom use during adolescence is an important component of SRH promotion.

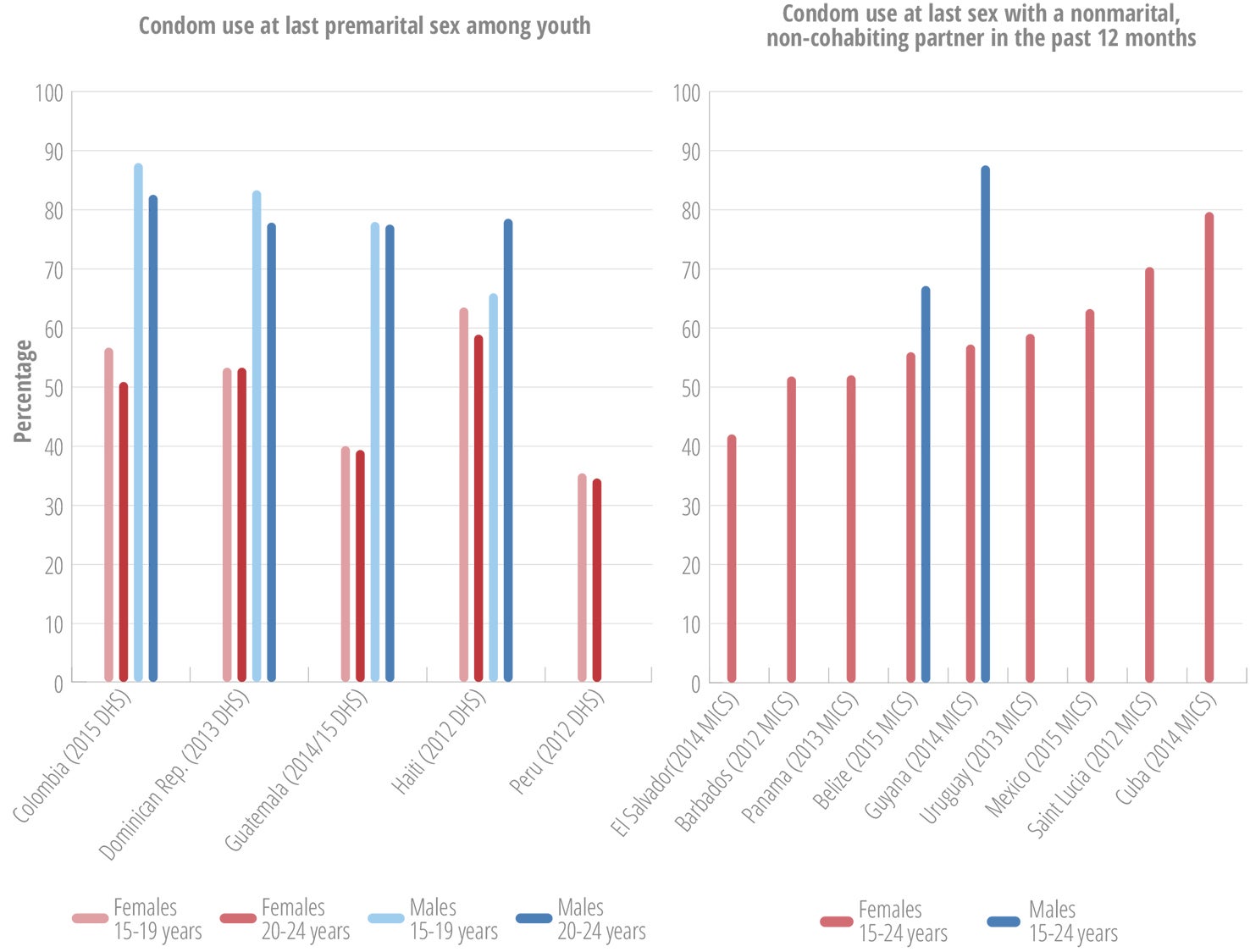

Several sources compile information on the use of condoms by young people. However, most such surveys of this kind are not conducted regularly by all countries, thus making it difficult to accurately assess patterns and trends in condom use among adolescents and youth. This subsection draws on data available from a variety of sources, including the MICS, DHS, and other studies conducted by individual countries. The specificity and comparability of the data depend on various aspects, including how the question is defined. The MICS asks about the use of condom at last sex with a nonmarital, noncohabiting partner in the past 12 months, by persons aged 15-24 years. In some countries the data are collected for females only, and in others this data is collected for males and females. The DHS uses the indicator of condom use at last premarital sex, defined as the percentage of young, never-married people (aged 15-24) who used a condom at last sex, out of all young single sexually active people surveyed.

Rates of condom use with nonregular partners differ noticeably in the Americas, and are consistently higher among males (Figure II.28). Peru had the lowest percentage of condom use among females, followed by Guatemala. Cuba had the highest reported percentage of condom use among females (Figure II.28).

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections

HIV

According to the United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), an estimated 76,000 adolescents aged 10-19 years and 223,000 young people aged 15-24 were living with HIV in LAC in 2016 (108), more females than males in the Caribbean, and more males than females in Latin America. Annex II.F provides an overview of the estimated number of adolescents living with HIV in LAC countries in 2015.

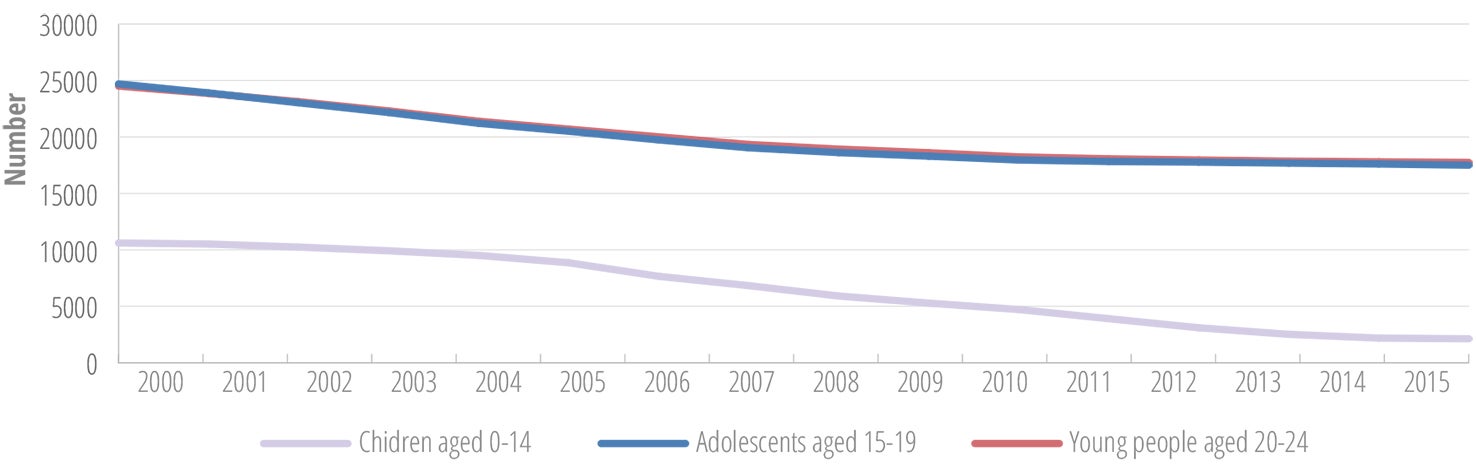

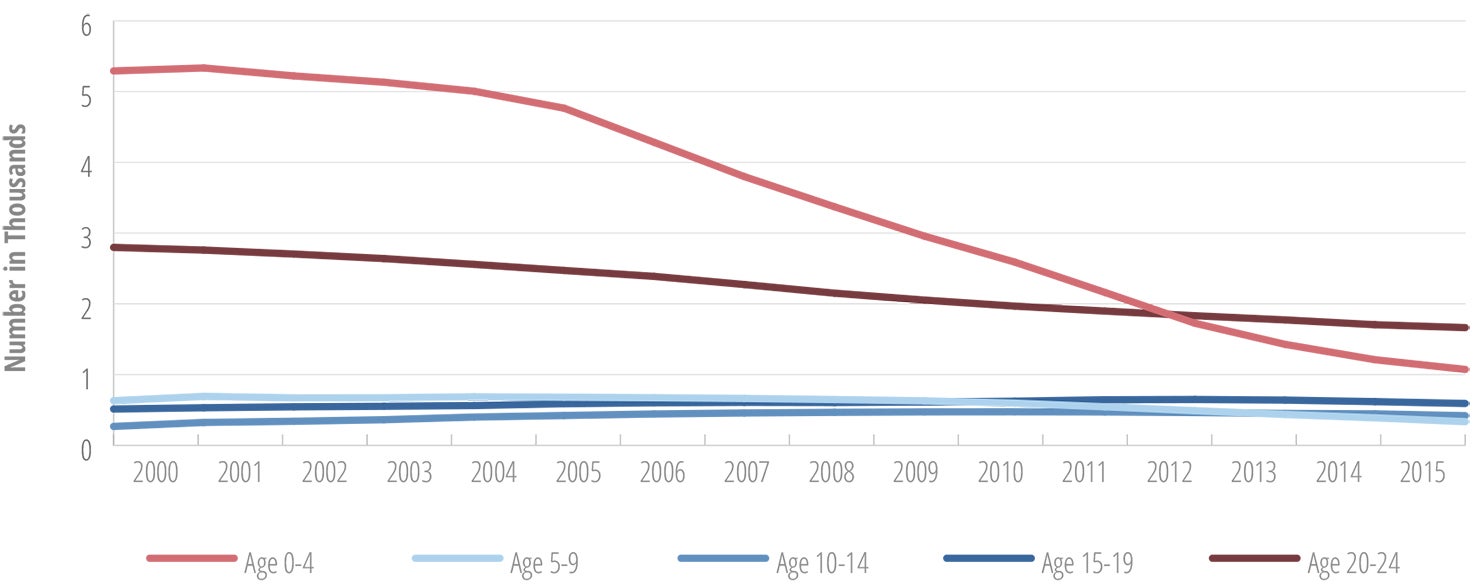

An estimated 19,300 new HIV infections occurred in the age group 15-19 years in 2016, and 39,600 in the age group 15-24 years (108). Between 2000 and 2015, the estimated number of new HIV infections in the age group 0-14 years declined by more than 60% in LAC due to the progress in the Region with the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In contrast, the decline in the estimated number of new infections in the age group 15-24 years has been much slower (Figure II.29) (108).

An estimated 2,600 young persons aged 15-24 years died in LAC in 2016 due to AIDS-related causes. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of AIDS-related deaths in LAC decreased sharply among children, and modestly in young people aged 20-24, while it shows a slightly increasing trend in adolescents aged 10-14 years and 15-19 (Figure II.30) (108).

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

The WHO estimates that more than 1 million STIs are acquired every day worldwide (109). This transmission takes place predominantly during sexual intercourse or other intimate genital contact. Some STIs can also be spread through nonsexual means, such as via blood or blood products, or from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth, and breast-feeding. There are more than 30 different bacteria, viruses, and parasites known to be transmitted through sexual contact. Eight of these are linked to the greatest incidence of sexually transmitted diseases: hepatitis B, herpes simplex virus (HSV or herpes), HIV, human papilloma virus (HPV), syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis. The first four are incurable, and the latter four are curable. Most STIs can be prevented through safe behaviors, such as consistent condom use, and two of them (HPV and hepatitis B) can be averted with vaccination. When STIs are symptomatic, the typical symptoms include vaginal discharge, urethral discharge or burning in men, genital ulcers, and abdominal pain. However, it is important to recognize that the majority of STIs are asymptomatic, without obvious symptoms of disease. Asymptomatic or subclinical infections cannot be identified without special testing, and therefore many infections are undiagnosed.

STIs are important causes of morbidity and mortality, given their contribution to complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, fetal and infant deaths, low birthweight and prematurity, and congenital infections. Studies have demonstrated a strong association between HIV infection and both ulcerative and nonulcerative STIs (110-112). There is also biological evidence that the presence of an STI increases shedding of HIV, and that STI treatment reduces HIV shedding (112). Mother-to-child transmission of an STI can result in stillbirth, neonatal death, low birthweight, prematurity, sepsis, pneumonia, neonatal conjunctivitis, and congenital deformities (110). HPV infection causes more than half a million cases of cervical cancer and a quarter million cervical cancer deaths each year (113).

Information regarding STIs in adolescents is very limited for several reasons. These include the complexities associated with conducting research with biological specimens among adolescents; the general lack of access for adolescents to SRH services, including STI services; the underestimation of the incidence and prevalence of STIs among adolescents due to the lack of data; reduced perception of risk or recognition of infection among adolescents; and the limited availability of noninvasive methods for STI diagnosis (e.g., urinalysis, self-collected vaginal swabs).

However, the limited number of studies that do exist indicate a significant STI burden among adolescents. This is true for young men who have sex with men (MSM), and also among young women. For instance, a recent small study conducted in northern Brazil found a chlamydia prevalence of 11% in a sample of 154 young women between 16 and 20 years of age (114). Similarly, some studies conducted in Latin America found chlamydia prevalence rates ranging from 7% to 31% among young women (115-116). A recent cost-effectiveness study conducted in the United States concluded that opt-out chlamydia testing for high-risk young women is cost-saving, because it improves health outcomes at a lower net cost, considering the costs of testing and the lifetime costs and quality-adjusted life expectancy associated with chlamydia infection (117).

A review paper looking at STI services for adolescents and youth in low- and middle-income countries concluded that adolescents in these settings tend to have limited knowledge regarding STIs, and they experience significant barriers in obtaining STI and SRH services. This can result in going untreated, onward transmission of STIs, and a greater risk for development of long-term and serious complications (118).

II.5 Nutrition and physical activity

Sound nutrition is an essential element of good health in adolescents. It improves school and educational performance, supports a stronger immune system, reduces the risk of disease across the life course, and, in the event of pregnancy, reduces the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. The available data on anemia, overweight weight, and obesity indicate that adolescents in the Americas face the double burden of malnutrition (characterized by micronutrient deficiencies coexisting with overweight, or obesity) (119-120). WHO defines overweight and obesity as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health, as measured through an index of weight-for-height or a body mass index (BMI). In children, overweight is defined as (> +1 SD) from the median for BMI for age and sex, and obesity as greater than plus two standard deviations (> +2 SD) from the median for BMI for age and sex.

Box II.4: Regional adolescent and youth health goal 6

Promote nutrition and physical activity

- Reduce the proportion of obese or overweight adolescents aged 13-15 years old

- Increase the proportion of adolescents 13-15 years of age who engage in regular physical activity

- Decrease the prevalence of anemia in adolescent women 10-19 years old

Source: (4).

In the majority of the countries with GSHS data, more than one in five of the students was overweight, in both males and females (Figure II.31).

a Overweight is defined as greater than plus one standard deviation (> +1 SD) from the median for BMI for age and sex.

Some DHS surveys provide data on overweight and obesity in females 15 years of age and older (Figure II.32). In addition, some countries conduct national health and nutrition surveys that also generate this data for different age groups. In these studies, a body mass index (BMI) between 25.0 and 29.9 is defined as overweight, and a BMI greater than or equal to 30.0 as obesity. In the 2012 national health and nutrition survey in Ecuador (121), 24.5% of females in the age group 15-19 years were overweight or obese (BMI greater than or equal to 25.0), and in the 2016 national health and nutrition survey conducted in Mexico (122), 36.3% of females in the age group 12-19 years were overweight or obese.

Figure II.32 also illustrates the temporal and cumulative dimensions of obesity and overweight. By age 24, the percentage of overweight or obese females has increased significantly in all these countries; in some instances it has doubled.

In the countries with two data points on weight in the GSHS and DHS, the majority show an increase in the percentages of overweight and obese females over time (Table II.7).

| Country (year of survey) | Global School-based Health Surveys (GSHS): changes in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents aged 13-15 years | |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage overweight | Percentage obese | |

| Argentina (2007) | 24.5 | 4.4 |

| Argentina (2012) | 28.6 | 5.9 |

| Guatemala (2009) | 27.1 | 7.5 |

| Guatemala (2015) | 28.0 | 7.7 |

| Suriname (2009) | 19.3 | 6.6 |

| Suriname (2015) | 28.6 | 11.6 |

| Demographic Health Survey (DHS): changes in the percentage of overweight and obesity in female adolescents aged 15-19 years | ||

| Colombia (2005) | 28.8 | 19.4 |

| Colombia (2010) | 31.1 | 22.1 |

| Haiti (2005-06) | 14.9 | 6.3 |

| Haiti (2012) | 17.4 | 7.8 |

| Honduras (2005-06) | 27.8 | 18.8 |

| Honduras (2011-12) | 29.2 | 22.1 |

| Peru (2007-08) | 34.4 | 14.6 |

| Peru (2012) | 36.5 | 17.9 |

| Demographic Health Survey (DHS): changes in the percentage of overweight and obesity in female youth aged 20-24 years | ||

| Colombia (2005) | 12.9 | 1.9 |

| Colombia (2010) | 13.9 | 3.6 |

| Haiti (2005-06) | 6.9 | 0.8 |

| Haiti (2012) | 5.7 | 0.5 |

| Honduras (2005-06) | 16.0 | 5.2 |

| Honduras (2011-12) | 15.8 | 5.2 |

| Peru (2007-08) | 18.5 | 2.2 |

| Peru (2012) | 18.8 | 4.0 |

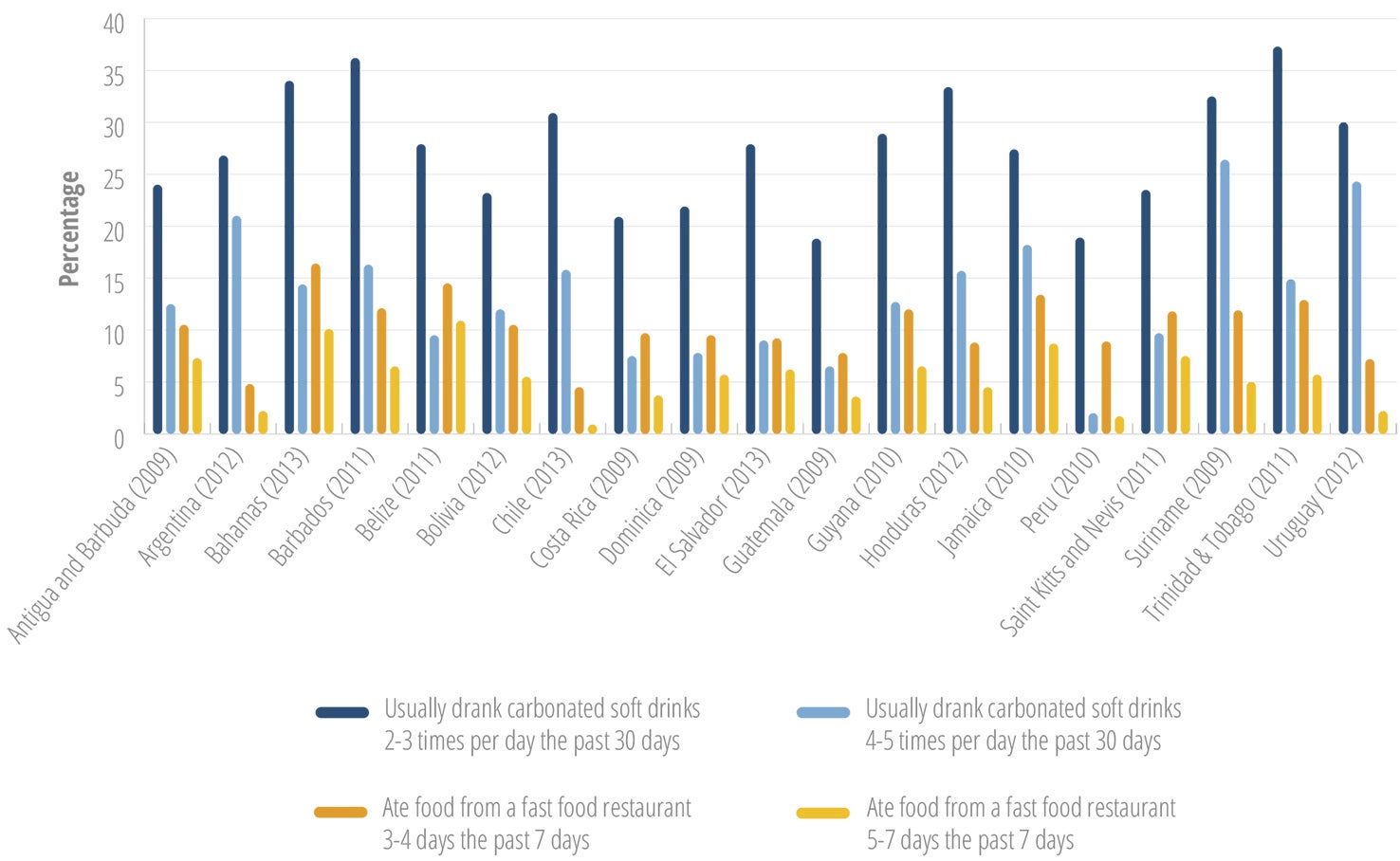

Key factors that promote weight gain and obesity include: a) high intake of products poor in nutrients and high in sugar, fat, and salt; b) routine intake of sugar-sweetened beverages; and c) insufficient physical activity (119,120). Adverse health consequences of obesity include increased risk of asthma, type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and cardiovascular diseases (119,120). These conditions can affect growth and psychosocial development during adolescence, with further repercussions across the life course.

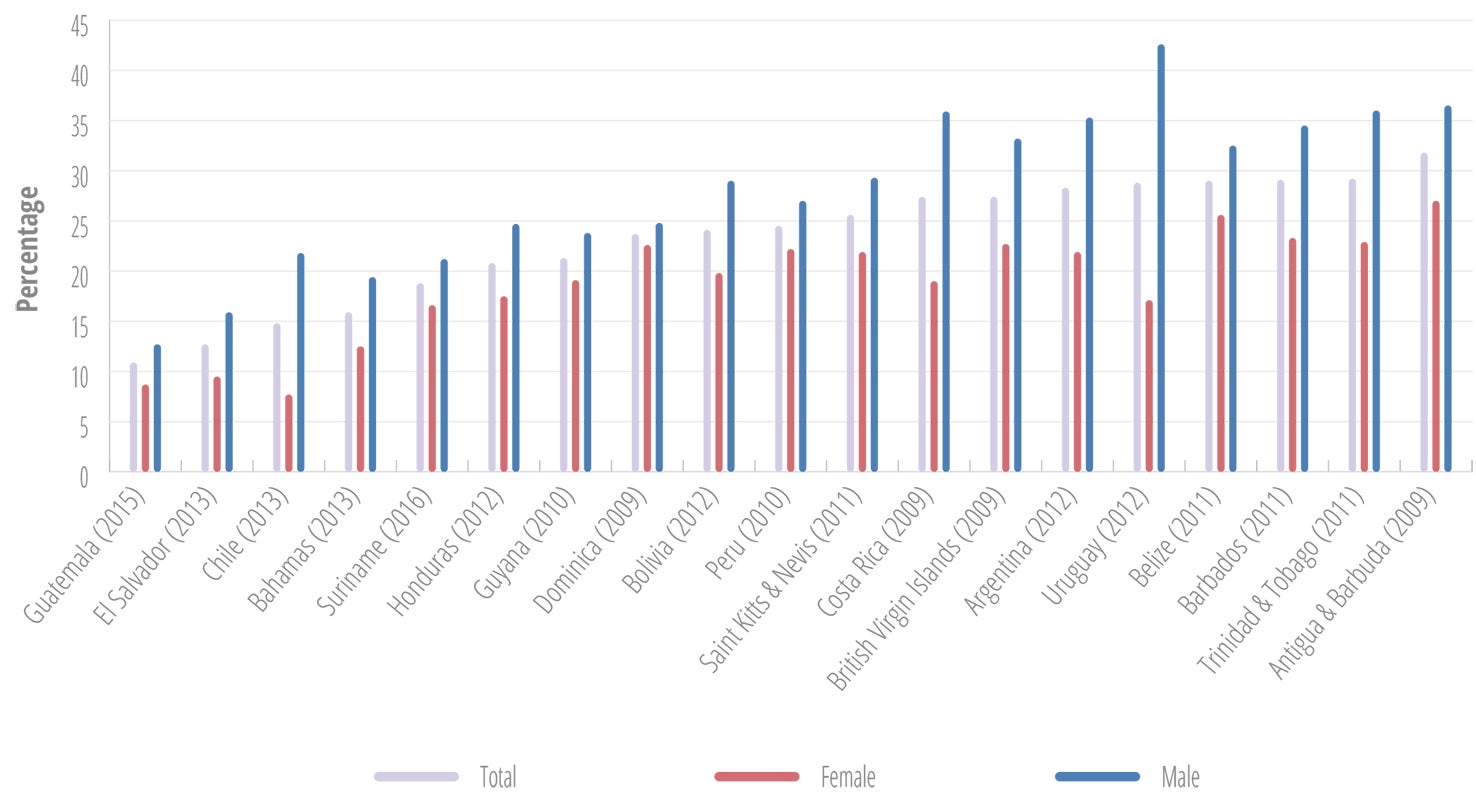

The level of physical activity among students aged 13-15 years in the LAC countries differs greatly, with consistently more males than females reporting regular physical activity (Figure II.33).

a For Suriname and Guatemala, the data reflect physical activity on all 7 days before the survey.

Considering the associations between consumption of sugary drinks and fast food, physical exercise, and the risk of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), the substantial number of young adolescents aged 13-15 who report frequently consuming soda and fast food is a major concern (Figure II.34).

In this context, PAHO has developed a Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents (124), to address the rapidly growing obesity epidemic in children and adolescents. Its goals include improving school food and physical activity environments, fiscal policies, and the regulation of food marketing and labeling. The plan also gives attention to gender and equity issues, recognizing girls are often more affected by the obesity epidemic.

Meanwhile, in 21 countries with data, 10% to 20% of the students indicated that they sometimes went hungry because there was not enough food in the home, which suggests significant levels of food insecurity in the Region. Notably, Jamaica had the highest percentage of students who sometimes went hungry (close to 30%) and also the highest percentage who regularly went hungry (at 10%) (81).These data fully support the conclusion of a double burden of malnutrition in the Region.

Anemia is a global public health problem most often associated with iron deficiency, which is the most widespread nutrient deficiency in the world (125, 126). Anemia is characterized by a reduction in the number of red blood cells and the oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin (125). WHO estimates that half of all anemia cases are caused by iron deficiency, with the remainder caused by other factors. Iron deficiency affects millions of individuals throughout the life course, especially infants and pregnant women, but also young children, adolescents, and women of childbearing age (127, 128).

The health and functional consequences of anemia include: an increased risk of maternal, fetal, and neonatal mortality; poor pregnancy outcomes such as low birthweight and preterm birth; impaired cognitive development, reduced learning capacity, and diminished school performance in children; and decreased productivity in adults (125). Research shows that children under 3 years of age, pregnant and nonpregnant women, and female adolescents are the groups at highest risk (125).

WHO has categorized the public health significance of anemia as follows (127):

- prevalence less than or equal to 4.9%, not a public health problem

- prevalence of 5% to 19.9%, mild public health problem

- prevalence of 20% to 39.9%, moderate public health problem

- prevalence above or equal to 40%, severe public health problem

Based on the WHO definition, anemia presents a severe public health problem in adolescents in Haiti, and a moderate public health problem in Guyana (Table II.8).

| Country (year of survey) | Age group | Percentage with any anemia |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (2012) | 10-19 years | 15.0 |

| Dominican Republic (2012) | 12-14 years | 13.4 |

| Ecuador (2011/13) | 15-19 years | 14.3 |

| Guatemala (2014/15) | 15-19 years | 11.7 |

| Guyana (2009) | 15-19 years | 34.1 |

| Haiti (2012) | 15-19 years | 55.5 |

| Honduras (2011/12) | 15-19 years | 12.5 |

| Mexico (2012) | 12-19 years | 7.7 |

| Peru (2012) | 15-19 years | 17.2 |

The WHO recommends various evidence-based interventions to encourage adolescent physical activity and healthy eating (Annex II.D3).

II.6 Chronic diseases

Oral health

Oral health is critical to overall health conditions in Latin America and the Caribbean. Scientific evidence shows that there is a strong interrelationship between oral health and general health, and that poor oral health is associated with a number of public health problems. For example, oral infections are linked with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, aspiration pneumonias, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Particularly in children and adolescents, poor oral health is associated with pain and difficulty eating. Poor oral health can also affect sleep patterns and influence growth and development.

In 2011, the UN Member States recognized the importance of oral health, through the Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases (129). That document focused on the four most prominent worldwide NCDs and their risk factors. The Member States recognized that renal, oral, and eye diseases pose a major health burden for many countries; that these ailments share common risk factors; and that these diseases can benefit from common responses to NCDs.

Box II.5: Regional adolescent and youth health goal 7

Combat chronic diseases

- Reduce the rate of decayed/missing/filled teeth (DMFT) for 12-year-olds

- Increase coverage of tetanus and diphtheria vaccine among those 10-19 years old

Source: (4).

The rate of decayed, missing, or filled teeth (DMFT) is an important indicator for measuring oral health conditions in countries. At the same time, attention should be given to the broader health implications of oral conditions. These include the associations between oral infections and systemic health; links between oral diseases and chronic diseases; and the onset of cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx, with its concomitant metastasis. While these aspects are not discussed in this subsection, they should be part of broader discussions on oral health in countries.

Data generated through oral health surveys in selected countries, with PAHO support, documented the status of countries along an oral health continuum, using the DMFT index. The DMFT is calculated on the basis of 32 teeth (i.e., all permanent teeth, including wisdom teeth), and is a unit of measurement that describes the number of caries in a population. In addition, PAHO has developed a typology to identify a country’s oral health profile. It is based on the DMFT index for children at age 12, with three stages of dental caries severity: 1) “emergent,” defined by a DMFT-12 score greater than 5 and the absence of a national salt and water fluoridation program; 2) “growth,” defined by a DMFT-12 score between 3 and 5 and absence of a national salt and water fluoridation program; and 3) “consolidation,” defined by a DMFT-12 score less than 3 and the presence of a national salt and water fluoridation program. The DMFT score facilitates reliable comparisons across countries.

From the 16 countries in the Region that conducted surveys during the 2005-2011 period, 15 were in the “growth” or “consolidation” stage, illustrating the progress made in the in the Americas towards improvement of the oral health of children and adolescents.

In this context, PAHO has been implementing a plan for improving oral health (130). The plan was approved by the PAHO Member States in 2006, and it urges Member States to recognize oral health as a critical aspect of general health. The policies, tools, and training that PAHO has provided to Member States have resulted in significant caries reduction throughout the Region. These improvements can be largely attributed to national preventive programs (including water and salt fluoridation), greater awareness of proper oral hygiene, and better oral health care practices. New, cost-effective approaches, such as fluoridation programs, have also been instrumental in facilitating greater access to oral health services, in particular for vulnerable groups.

Vaccine coverage

WHO recommends that all individuals should receive a total of five doses of a tetanus toxoid vaccine, followed by a booster dose at the beginning of adult life to ensure protection throughout reproductive life, and possibly provide lifelong protection. Because there is evidence that a series of five doses of vaccine provides virtually 100% protection, most countries in the Region have a tetanus vaccination schedule that includes three doses of vaccine in the first year of life, plus two booster doses before 7 years of age (which also strengthen protection against pertussis). In addition, all women of childbearing age without registration of at least five doses of a vaccine containing tetanus toxoid should receive the necessary doses of tetanus vaccine for prevention of neonatal tetanus.

In 2015, 15 countries in the Region reported to PAHO that they had vaccination coverage of 85% or higher with a fifth dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine. There is no specific recommendation for vaccination of adolescents with Td4 in the Region of the Americas. PAHO is continuing to work with all the countries in the Region to assure early protection against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis, with a schedule of five doses of DPT vaccine before 7 years of life.

4 Td = tetanus + reduced content diptheria

An important addition to the adolescent immunization schedule is the vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus that causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer is caused by the sexually transmitted HPV, which is globally the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract. Almost all sexually active individuals will be infected with HPV at some point in their life, and the peak time for infection is shortly after becoming sexually active. The majority of HPV infections resolve spontaneously and do not cause symptoms or disease. However, persistent infection with specific types of HPV may lead to precancerous lesions that can progress to cervical cancer if left untreated (131).

In spite of the challenges associated with introducing a new vaccine and the many myths around HPV vaccine that create barriers for its uptake, the Region of the Americas has made significant progress in the introduction and expansion of HPV vaccine for adolescents. As of March 2017, at least 29 countries in the Region had introduced public HPV vaccination programs. The majority of these programs target adolescent girls. The countries that provide HPV vaccine for both boys and girls include Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Canada, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the United States. Based on country reports to PAHO, by the end of 2016, full-course HPV vaccination coverage according to national guidelines averaged 55% in the Region of the Americas.

II.7 Protective factors

In addition to immediate health outcomes, the Regional Strategy and the Plan of Action on Adolescent and Youth Health have included attention to the risk and protective factors that are important determinants for health and disease in adolescence, in particular health-related behaviors and conditions. These include a focus on parents’ connection with and regulation of adolescents, with the collection of information about how often during the preceding 30 days parents or guardians checked that homework was done, understood their adolescents’ problems and worries, or really knew what the adolescents were doing with their free time.